|

|

The Decorated Caves of the Upper Palaeolithic |

Page 2/5 |

Dedicated Temple Caves

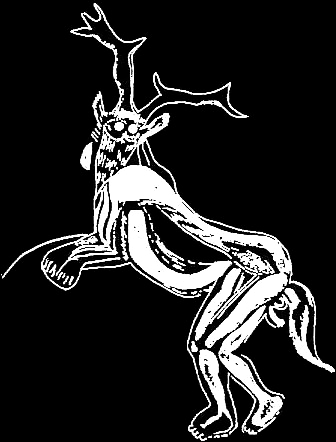

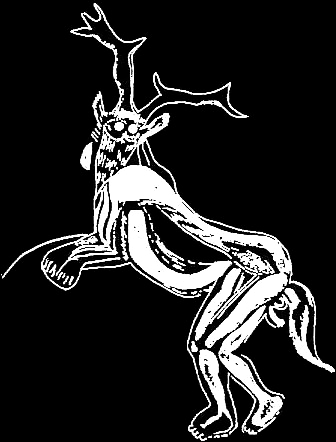

Whilst no decorated cave of the Upper Palaeolithic is like any other and each has its own individual character, there is yet a striking uniformity between them. Here are just some of the most obvious common features. All the decorated caves depict animals, rather than human beings (though there are a few exceptions to this general rule such as, for example, the stick-figure in the cave of

Lascaux thought to be that of a shaman in a trance, or the figure in the cave of Les Trois Freres, a composite being, part man, part beasts, usually referred to as the 'sorcerer'). The paintings of the animals are carried out with the utmost care, displaying as much the artists intimate familiarity with the natural world as their highly developed artistic skills. Of the very many instances illustrating this point only a few can be mentioned here, such as the magnificent 'Hall of Bulls' in

Lascaux; the large black stag with spectacular antlers or the frieze of small horses, both in

Lascaux. In the relatively recently discovered

Chauvet Cave there is a rock-face showing the so-called 'Chagal Horses', astonishingly accurately observed and drawn; also in

Chauvet is a panel depicting a pack of cave lions, their bodies and particularly their eyes full of hunger for their prey. Again, there are bison panels in the Salon Noir of the

Niaux Cave where the animals' eyes, tapered horns and hooves and their thick woolly manes are rendered with such detail that one imagines that they might step off the wall at any moment.

The image-makers of parietal (cave) art were selective in the type of animals they represented, that is, instead of depicting the animals that provided their daily sustenance, they chose to focus on the animals of the hunt, with horses and bison being the most common. Most animals are given in profile whilst all of them - without exception - are drawn without a background or a solid base-line for support which gives the impression that they are floating in space.

Niaux Cave Bison

Sallon Noir

Another common feature is that the embellished chambers of the Palaeolithic caves are never found at or near the entrance but always in the deepest and most hidden parts of the caves, which could only be reached by men willing to risk life and limb to get there. Moreover, the Ice-age artists did not paint just on any rock-face but carefully searched for specifically shaped rocks which with their contours suggested the outline, the head, or the eye of an animal. In the Sallon Noir of

Niaux, for example, the painter used a deep, black hole in the rock for the eye-socket of a magnificent bison and then guided by the stone composed the whole animal around it. Elsewhere a craggy gap in the rock inspired the artist to see a deer head emerging from behind the rock - all he had to do to complete the image, was to draw the antlers. In their determination to find the right spot, the rock painters would have had to carefully scan the surfaces, climb up to slippery ledges near the ceiling of the cave, or else, scramble down into narrow recesses. All in all, it would have been a task that required supreme courage and agility. Since the search would have been done by the flickering light of hand-held torches, touch would have played an important role - a point whose significance will become clear shortly.

If we add to these common features the fact that the Palaeolithic tradition of decorating the deepest parts of caves continued over a very long period of time, spanning more than twenty thousand years from ca. 34 000 BC to ca. 12 000 BC, the time of the great Ice-age hunt, a central theme or leitmotif begins to emerge. And it is this: these extremely remote decorated chambers could have never served as shelters or dwelling places since they are too far from the entrances and exits, and often in the most extreme places. The question is: what were these places used for? Archaeologists and art historians of this period are almost universally agreed that these inaccessible spaces must have been used as underground temples, as sanctuaries, for carrying out religious, and/or shamanic rituals. Mighty chance creations of nature such as the magnificent caves of

Lascaux,

Chauvet,

Niaux, Les Trois Frères, etc., would probably have been particularly sought out by Palaeolithic man as sacred places full of mana, places where the divine spirits could be evoked for their oracular wisdom, or places where the artist could relive and speculate on the exhilarating and sometimes terrifying experiences of the hunt.

Further Reading:

→

Palaeolithic Cave Art and Depth Psychology by Dr. Ilse Vickers

→

Bradshaw Foundation Homepage

→

French Cave Paintings & Rock Art Archive