Ancient cave paintings and rock engravings can be found on every continent. Clearly it was a practice of great importance - not merely 'art for art's sake' - carried out by hunter-gatherer societies. By studying this practice on a global scale, the art reveals similarities in both style and subject. The similarities are evident even though the artists could not have been influenced by one another.

The whole story may indeed have a very human explanation - one that involves common anatomical and neurophysiological characteristics.

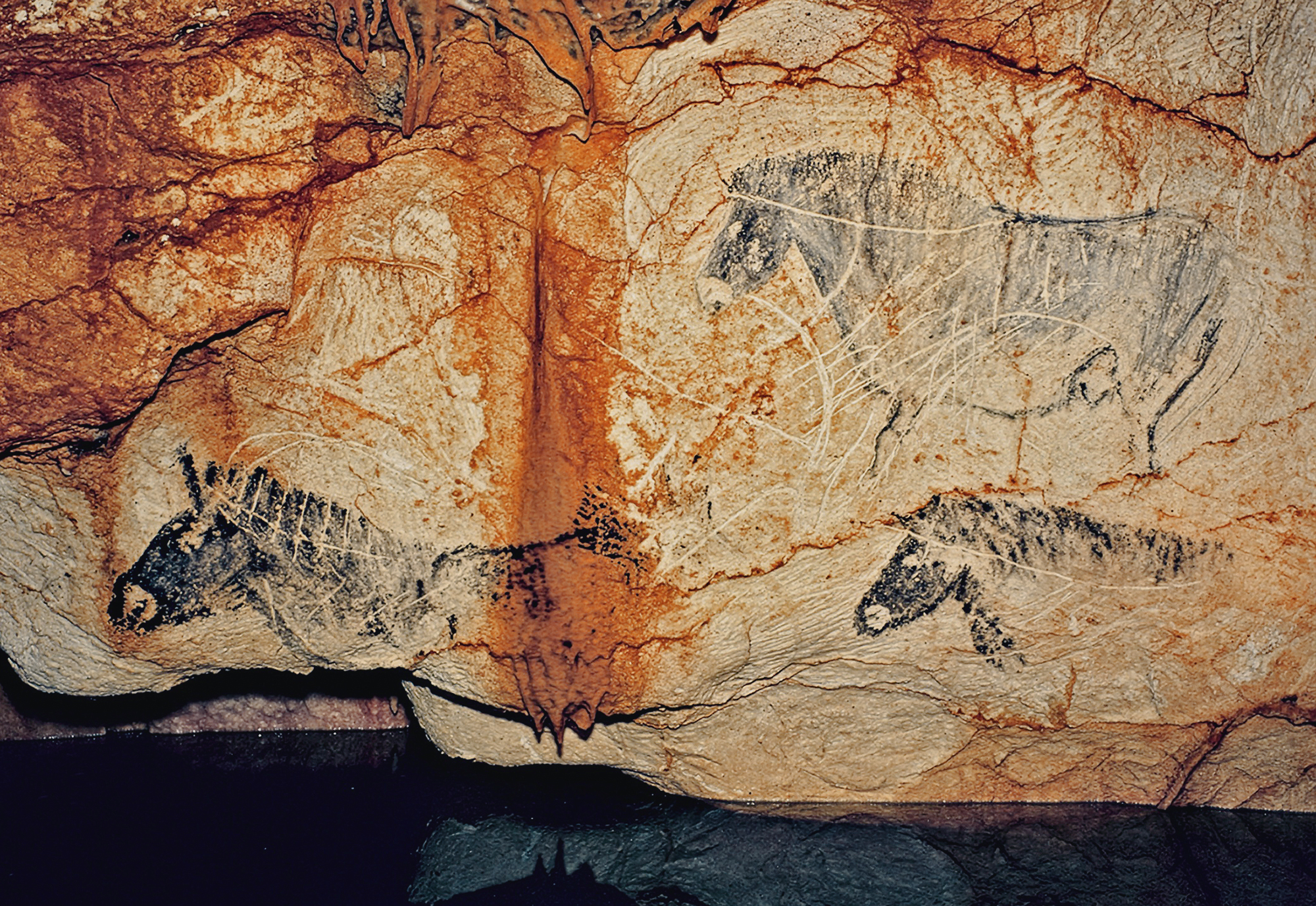

The common perception of prehistoric rock art involves depictions of animals. These depictions are largely representational. Whether it is the bulls of Altamira, the 'Chinese' horses of Lascaux, the mammoths of Rouffignac or the rhino and lion paintings at Chauvet, Paleolithic art and animals are tightly intertwined - Palaeolithic art, from beginning to end, is an art of animals. In Europe for example, most of the animals represented are large herbivores, those that the hunter-gatherer societies could see around them and which they hunted.

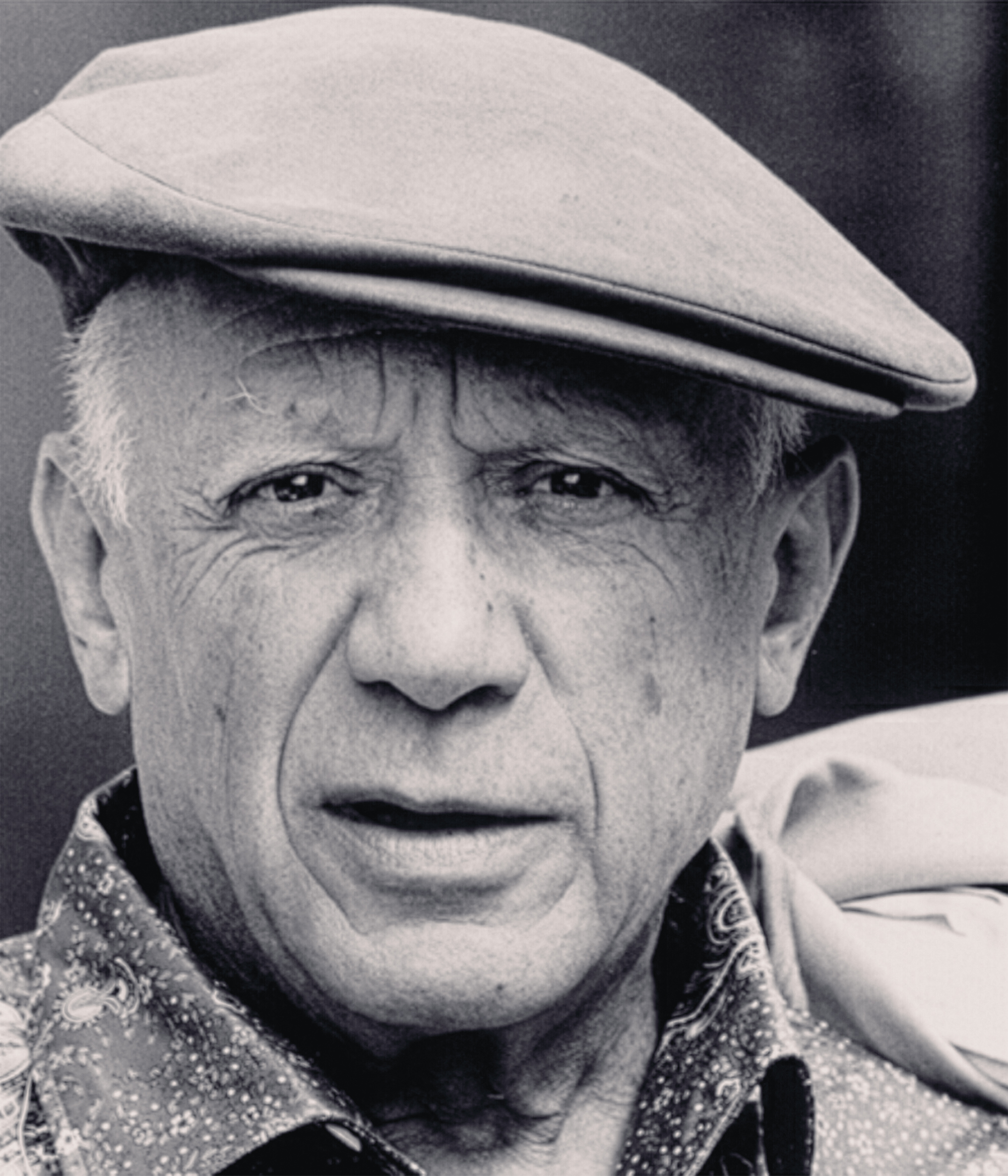

When it comes to similarities in style, however, another question should be asked: are there 'universals' in artistic tendencies? The style of an image is often repeated over time. Now that Chauvet has been discovered and dated, we know that some of the earliest artistic images known to humankind bear a remarkable resemblance to more modern works of art. The freshness and 'modernism' of the Chauvet images can be readily compared with those of Chagall and Marc. A recent exhibition on Ice Age art in London's British Museum juxtaposed works of art from the Ice Age with those of the Twentieth Century. When the paintings of Altamira were first discovered in 1879 they were labeled a hoax because of their resemblance to the Impressionist style of painting. And it was Picasso, who on viewing the paintings of Lascaux in 1940, declared "we have discovered nothing". Was he referring to 'universal' artistic tendencies?

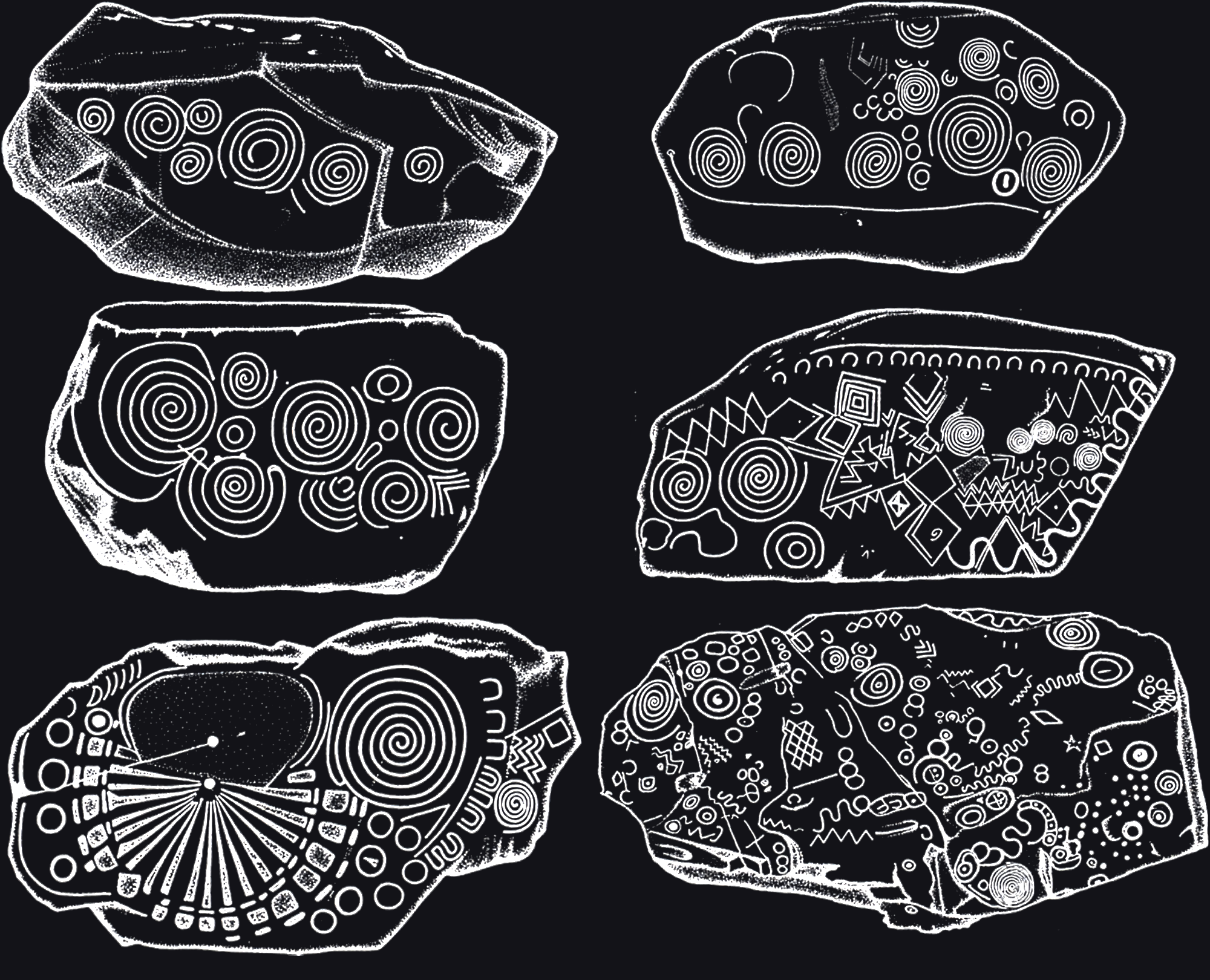

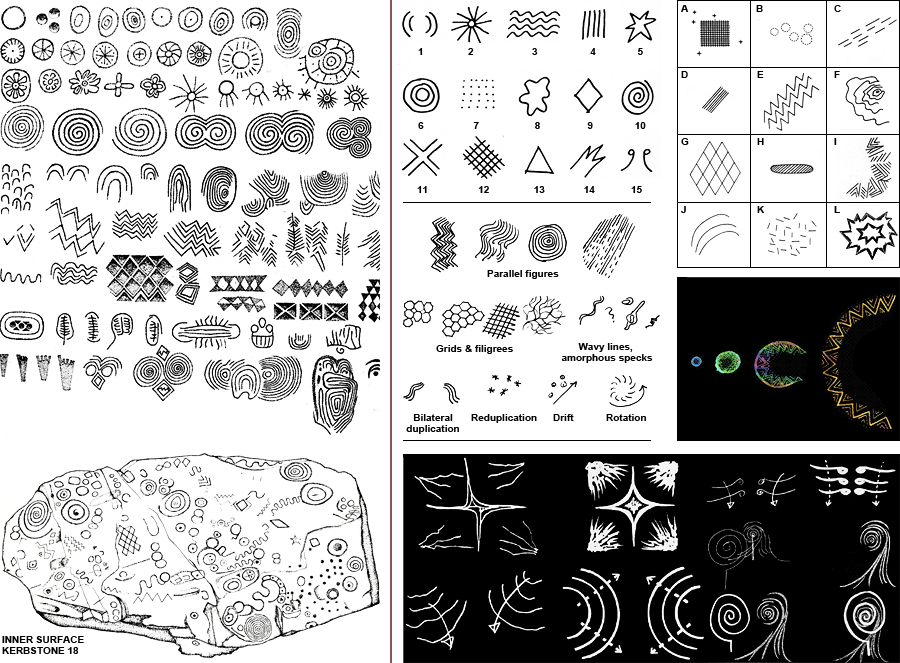

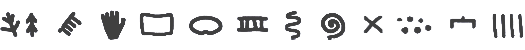

The concept of 'universals' is even more apparent in the geometric symbols - as opposed to the 'figurative' - of prehistoric art.

Geometric Palaeolithic Signs are found at nearly all decorated Upper Palaeolithic sites in Western Europe. Indeed, they are found throughout the world, but the meanings they hold remain elusive. Some symbols may have been stylized from mundane images of everyday life - tools, weapons, housing - and some may have been truly abstract shapes which could very well be symbolic representations of important concepts and ideas, or the manifestations of transcendent, shamanistic experiences in the form of visual hallucinations. We do not yet know the precise meanings of these symbols, but perhaps there is a way - a hypothesis - to begin to explain their universality across time and location: geometric forms seen in prehistoric rock art emerge from the anatomical and neurophysiological characteristics of the human visual cortex.

Let us explore whether these symbols are universal, and whether they emerge from some aspect of the structure or function of the human mind that has not changed fundamentally across all of this time and dispersion throughout the world.

By looking at the neurological origin of the symbols, we cannot shed light on the symbolic significance of the geometrical images. In fact, these meanings will vary, we assume, from culture to culture. A deeper understanding of meaning is beyond the realms of this hypothesis.

One of the most common geometric motifs is the spiral, painted and carved throughout the world. And yet the symbolic meaning of the spiral in prehistoric art is speculative. Some argue it may have represented the sun, or the portal to a spirit world. Perhaps it represented life itself, or life beyond life - eternity. Or else, it may have had a more prosaic, functional purpose, that of a calendrical device, employed to deconstruct time into chapters, seasons and solstices.

From the painted and engraved walls of the Upper Palaeolithic to the decorated megalithic standing stones of the Neolithic, the symbols persisted. In Europe, the megalithic art of Ireland featured the spiral intensively.

At Brú na Bóinne, a significant center of human activity for almost 6,000 years, the spiral symbol is a dominant feature. The site is a complex of Neolithic mounds, chamber tombs, standing stones, henges and other prehistoric enclosures. The major sites within Brú na Bóinne are the impressive passage graves of Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth, each standing on a ridge within the river bend. Each of the three main megalith sites have significant archaeoastronomical significance. It is thought that Newgrange and Dowth have winter solstice solar alignments, and Knowth has an equinox solar alignment.

Knowth is the largest of all passage graves situated within the Brú na Bóinne complex. The site consists of one large mound and 17 smaller satellite tombs. The large mound is roughly 12 metres in height and 70 metres in diameter. It contains two passages, placed along an east-west line. The passages are independent of each other, and each leads to a ceremonial chamber. The mound is encircled by 127 kerbstones.

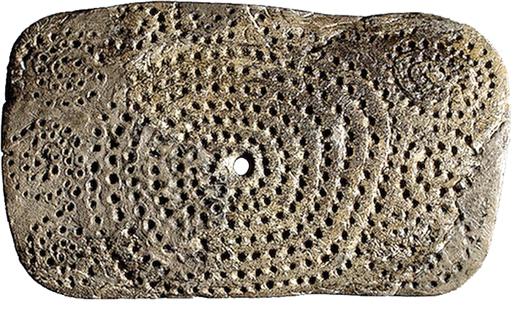

The kerbstones, large blocks of decorated stone, are adorned with geometric patterns, including spirals. The patterns on several stones (not shown here) have been interpreted as calendrical devices that enable the calculation of the synodic and siderial months and the exact length of the year. They suggest an awareness of a 19-year lunar cycle.

Spiral symbols that were probably not related to any calendrical functions occur on two artifacts created at totally different scales of construction, at widely separated locations and times. At the grand scale is the 2,000 year old Serpent Mound in Ohio, North America. At a much finer scale is the 18,000 year old spiral-engraved mammoth ivory piece, discovered in Siberia at Mal'ta to the west of Lake Baikal. If not calendrical devices, what were the symbolic significance of these spirals? Even though the meanings may never be known with certainty, their forms may have emerged from the same neurological wellspring as the megalithic spirals in Ireland.It is worth noting that other than the portable mammoth ivory piece, the spiral motif is rare in European rock art sites from the Upper Palaeolithic [approximately 40,000 to 12,000 years ago]. According to Genevieve von Petzinger, it is strange that it is not present more often considering that it is a very common entoptic shape reported in trances, and how central this motif becomes in later time periods. To her this lack of spirals in the Upper Palaeolithic raises some very interesting questions about where people were getting their inspiration for the non-figurative art (possibly altered states of consciousness were not a regular phenomenon yet) as well as the choices they were making about what to depict or leave out. The use of the spiral does not become a regular occurrence in Europe until after the Upper Palaeolithic and that the mystery of why not still remains to be solved.

In the Americas, however, the spiral symbols were not rare. They are infact very prevalent in the rock art during a period that was culturally equivalent to Europe's Upper Palaeolithic. Many of the sites in the Americas where spirals are prevalent are thought to be associated with cultural use of hallucinogenic drugs or rituals.

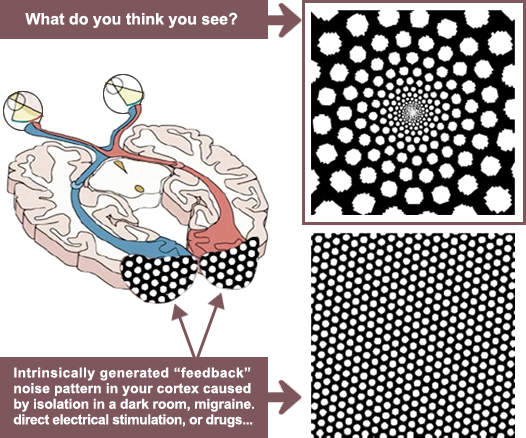

The ubiquitous nature of geometric motifs, such as the spiral, clearly raises the question: What is the art saying? It also raises another question: What relationship do geometric motifs have with the human nervous system, with hallucinations, for example? We need to understand the relationship between brain, vision and interpretation. What is the cortical basis for geometrical visual hallucinations? What causes these geometric patterns [and even more complex patterns] to be generated in the cortex?

The scientific literature has a host of images drawn by people during or directly after they were experiencing hallucinations induced by drugs, or direct electrical stimulation of the visual cortex of the brain. One can argue that there is a clear commonality between hallucinations and prehistoric geometric motifs, such as the kerbstones at Brú na Bóinne.

The geometric forms seen in visual art - in art of great antiquity - are equivalent to the patterns seen as visual hallucinations during migraine headaches, during prolonged visual deprivation, during 'near death experiences', after ingestion of psychedelic drugs, or during direct electrical stimulation of the brain. Modern experiments show that these geometrical forms emerge from the characteristics of the human brain.

The universal geometric motifs emerge from activity in what is known as the primary visual cortex of our brains. This is the very first stage of processing, where the information captured by our eyes enters the cortex of our brains. The geometric forms can be perceived directly during hallucinations, and this supports the hypotheses by Heinrich Klüver, David Lewis-Williams and Jeremy Dronfield, that rock paintings by shamanistic artists are simply an accurate record of the artists' visions: the artists could have been drawing what they were seeing, in a very literal sense. It is possible that these geometric motifs are infact 'natural motifs' for our brains. We are now in the realm of 'geometric neuro-aesthetics'.

Most people will be able to notice patterns with careful concentration under the correct conditions. When the eyes are closed, many very dim images will be perceived, such as a ripple pattern. These ripple patterns are known as 'drug-free hallucinations', and emerge from the baseline activity of the part of the human brain that mediates the visual perception.

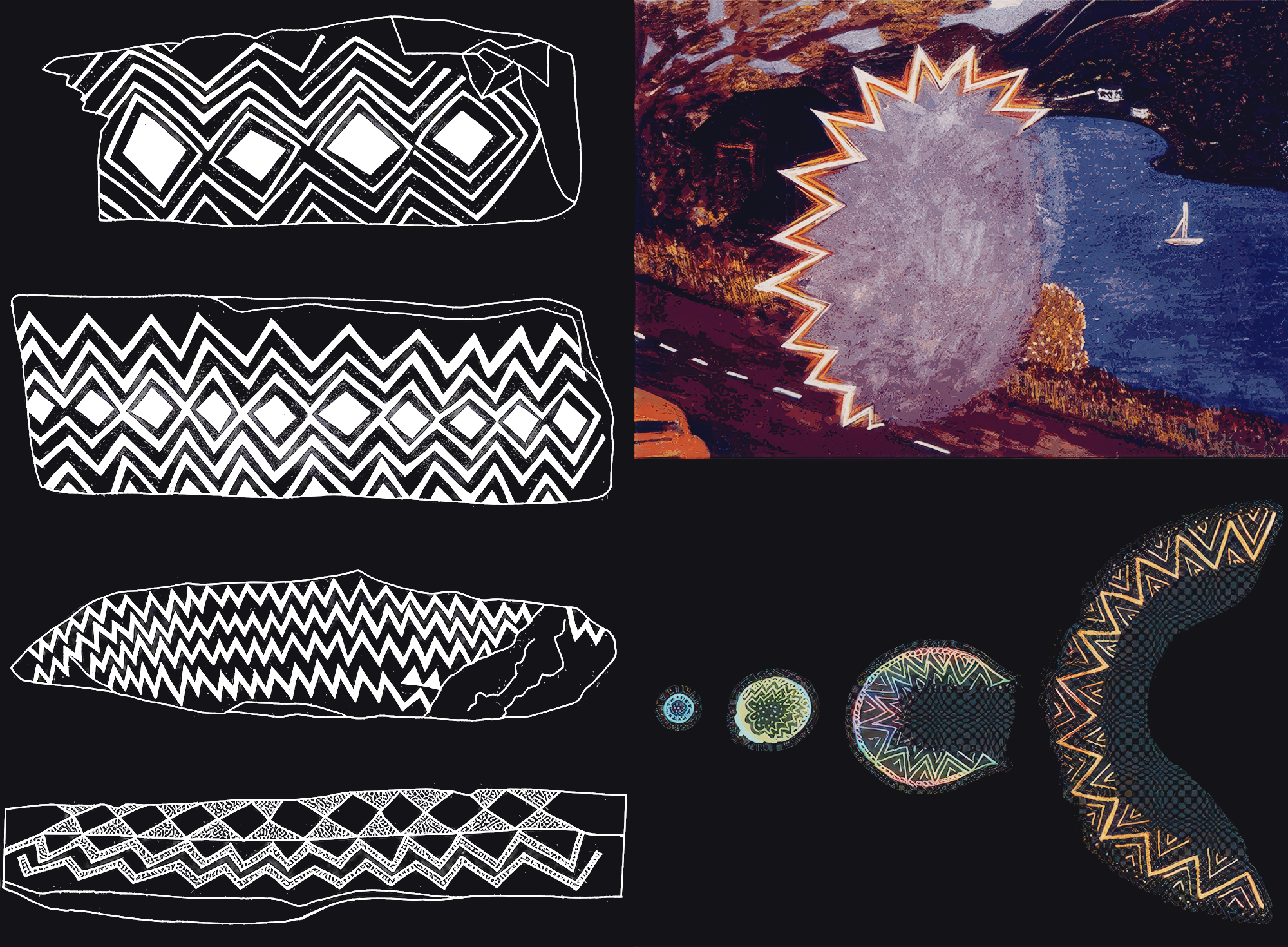

Other examples of drug-free hallucinations are the dynamic, jagged geometric patterns called 'fortification patterns' that often accompany migraine headaches. The image of jagged patterns around a dark visual 'hole in the universe' bears a striking resemblance to the manner in which the entry portals into the Passage tombs in Ireland were decorated. The decorated lintel stones placed over the dark entrance tunnels into the tombs may be a direct representation of patterns seen by the artists. Are there hallucinations that correspond to the other geometric forms besides those induced by migraines?

(Top) Fourknocks, Central Recess Lintel. (Middle Top) Fourknocks, West Recess Lintel. (Middle Lower) Fourknocks, Entrance Lintel. (Lower) Newgrange, Corbel in Chamber.

RIGHT

Fortification patterns recorded by migraine sufferers.

Is there an underlying source to account for this geometric universality? Not a supernatural source, but a cerebral source, where the images emerge naturally from the structure of the brain, and work their way into all visual art forms, even those that do not involve drugs or hallucinations.

Neuroscience research reveals that these geometrical forms emerge from the characteristics of the human brain that we all share; characteristics of the human brain that were established by our hominid ancestors hundreds of thousand years ago.

Nerve cells from the eyes connect to the cortex in the back of the brain and form a distorted map of what is being seen. A neuroscientist named Eric Schwartz studied the nature of this distortion, and showed how to transform any visual scene, for example, a face, into the pattern of activity it would generate in our visual cortex. This is a two-way process: the model can predict what you are seeing, based on the activity pattern that is generated back in the cortex.So how does this relate to universal geometrical motifs?

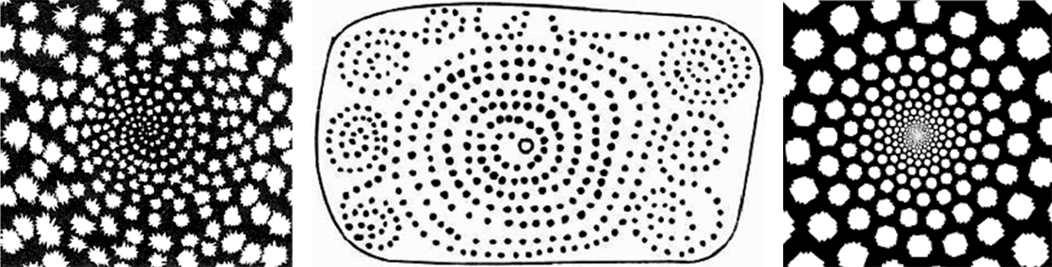

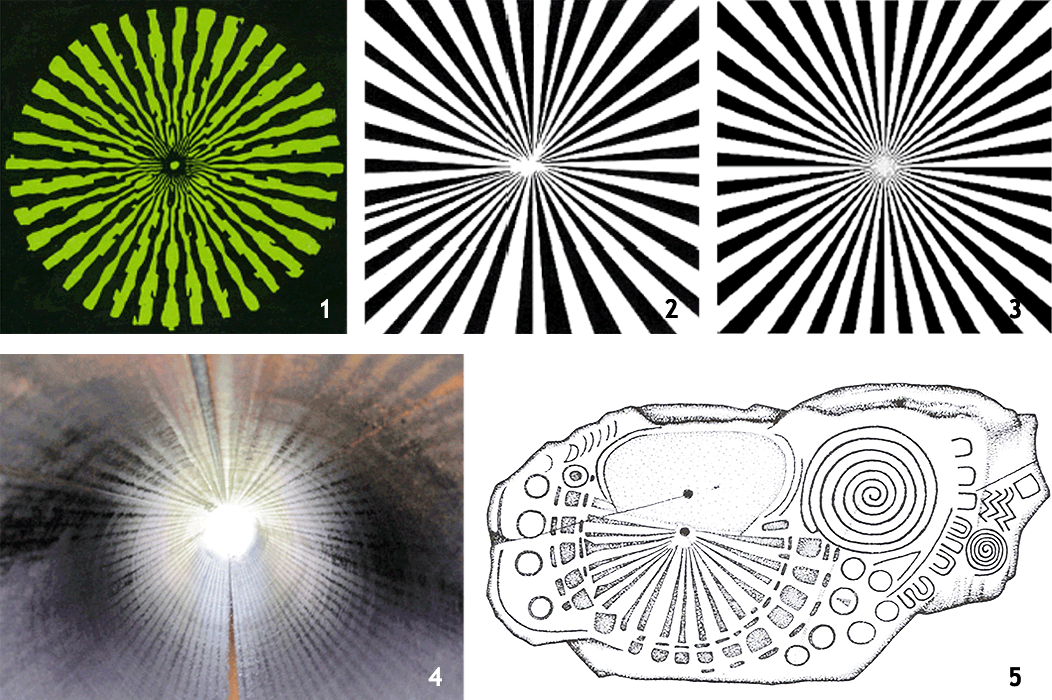

Based on extensive research about the properties and interconnections of the nerve cells in our visual system, neuroscientists can now predict the activity patterns that would be generated in the visual cortex in response to hallucinogenic drugs, near-death experiences, migraine headaches, or prolonged isolation in the dark. Professors Bard Ermentrout and Jack Cowan showed that those conditions would lead to frenetic brain activity, rather like the audio feedback generated by a microphone placed too near to the output speakers of a high-gain PA system. Dr. Cowan, Dr. Paul Bressloff and several of their colleagues extended the earlier models, and derived a whole set of cortical patterns can be matched to the visual hallucinations that would be perceived during that activity.

These predicted hallucinations are very similar to the real, recorded hallucinations. Therefore a plausible hypothesis may be that prehistoric rock paintings and geometric art forms are simply an accurate record of the artist's vision. However, was the artist who created the 18,000 year-old mammoth ivory plaque from Siberia doing so under the influence of drugs, migraines or near-death experiences, or was this simply a pleasing and meaningful pattern? Similarly, the predicted hallucination ray patterns that come out of the computer model of the visual cortex bear a striking resemblance to the prehistoric engravings on one of the Knowth kerbstones.

1. LSD hallucination, from Oster (1970)

2. LSD hallucination, from Siegel (1977)

3. Predicted hallucination from mathematical model by Bressloff et al

4. Image representing a person's near-death vision

5. Megalithic kerbstone from Knowth, Ireland

In the eternal question of what inspires art, modern science may appear to have some answers. But can this modern approach unlock the secrets of a prehistoric past? Can they determine the influences of ancient artistic endeavour?

It is possible that the geometric motifs appear in the art of hallucinators as well as non-hallucinators; for the latter because these forms are 'natural motifs' for our brains. The geometric motifs that occur most frequently in works of art that we consider pleasing may be the ones that activate the natural baseline activity modes of the visual cortex: they may be more effective at stimulating a large-scale pattern of activity in the visual cortex, and more aesthetically pleasing than motifs which do not correspond to the intrinsic patterns of activity.

Therefore it is the structure of the visual cortex which might explain some fundamental shared aspects of our artistic aesthetics.