An online article by Nicholas Wade on the NYTimes - Otzi the Iceman's Stomach Bacteria Offers Clues on Human Migration - reports on the insight into the peopling of Europe, based on an unlikely source - the stomach contents of a 5,300-year-old body pulled from a thawing glacier in the eastern Italian Alps.

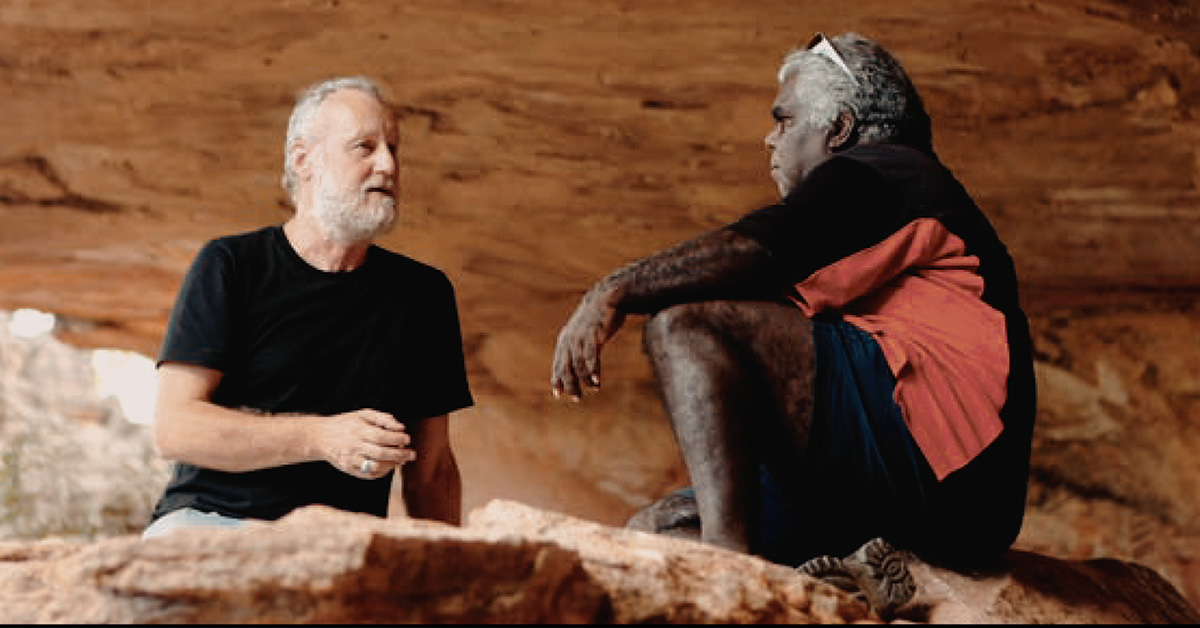

Scientists studied a bacterium found in the stomach of the mummified man nicknamed Otzi the Iceman, seen here in a photograph released by the University of Camerino, in Italy, in 2008. Image: CreditFranco Rollo/Agence France-Presse - Getty Images

Since his discovery in 1991, Otzi the Iceman, as he was named, has provided a trove of information about the life of Europeans at that time. His long-frozen tissues have now yielded another surprise: Scientists have been able to recover from his stomach samples of Helicobacter pylori, a bacterium that infects about half the human population and can occasionally cause stomach ulcers.

The bacterium is transmitted only through intimate contact, and its distribution around the world matches almost perfectly the distribution of human populations. The bacterium's genetic variations are therefore used by researchers as a supplement to human genetics in tracking ancient human migrations.

Researchers led by Frank Maixner and Albert Zink of the Institute for Mummies and the Iceman, at the European Research Academy in Bolzano, Italy, reported on Thursday in Science that they had been able to reconstruct the entire DNA sequence of the ulcer bacterium from samples taken from the iceman's stomach.

Modern-day Europeans carry a type of H. pylori that is a hybrid of two ancient strains, one of which originated somewhere in Eurasia and the other in Africa, after modern humans first left that continent about 50,000 years ago.

One theory is that this hybridization occurred in the Middle East before or during the Last Glacial Maximum, a catastrophically cold period during the last ice age when glaciers swept south and made much of Europe uninhabitable.

After the glaciers began to retreat, about 20,000 years ago, people from the Middle East and other southern refuges moved north to recolonize Europe. It could have been these migrants who brought the hybridized ulcer bacterium to Europe.

Yet the ulcer bacterium from Otzi is related only to the Eurasian strain, the researchers found, implying that hybridization with the African strain must have occurred much later, within the last 5,000 years.

The finding suggests that it may have been the first farmers, who brought the agricultural revolution to Europe from the Middle East starting about 8,000 years ago, who were the carriers of the African strain, said Yoshan Moodley of the University of Venda in South Africa, a co-author of the new report.

Reconstructing the history of human pathogens, a new science made possible by the ability to decode DNA molecules many thousands of years old, can yield deep insights into both medicine and history. Last October a team led by Eske Willerslev of the University of Copenhagen extracted Yersinia pestis, the plague bacterium, from human teeth up to 5,000 years old.

The plague bacterium, spread by fleas and rats, caused three devastating pandemics - the Justinian plague of the sixth century, the Black Death in 14th-century Europe and the global pandemic that erupted in the 1890s.

Mark Achtman, a leading expert on ancient pathogens at the University of Warwick in England, said that the authors of the Otzi paper had done well to extract the ulcer bacterium from the iceman, but that it was difficult to infer from a single sample anything about the bacterium's distribution in Europe 5,000 years ago.

Besides looking at the DNA of the ulcer bacterium, the authors also found proteins in the iceman's stomach that are involved in inflammation, but the stomach is too poorly preserved to confirm that he suffered from gastric disease.

Visit the Journey of Mankind: the Peopling of the World, based on the research of Professor Stephen Oppenheimer:

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/stephenoppenheimer/index.php

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 25 June 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 09 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 03 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 28 October 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 February 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 28 November 2019

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 25 June 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 09 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 03 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 28 October 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 February 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 28 November 2019

Friend of the Foundation