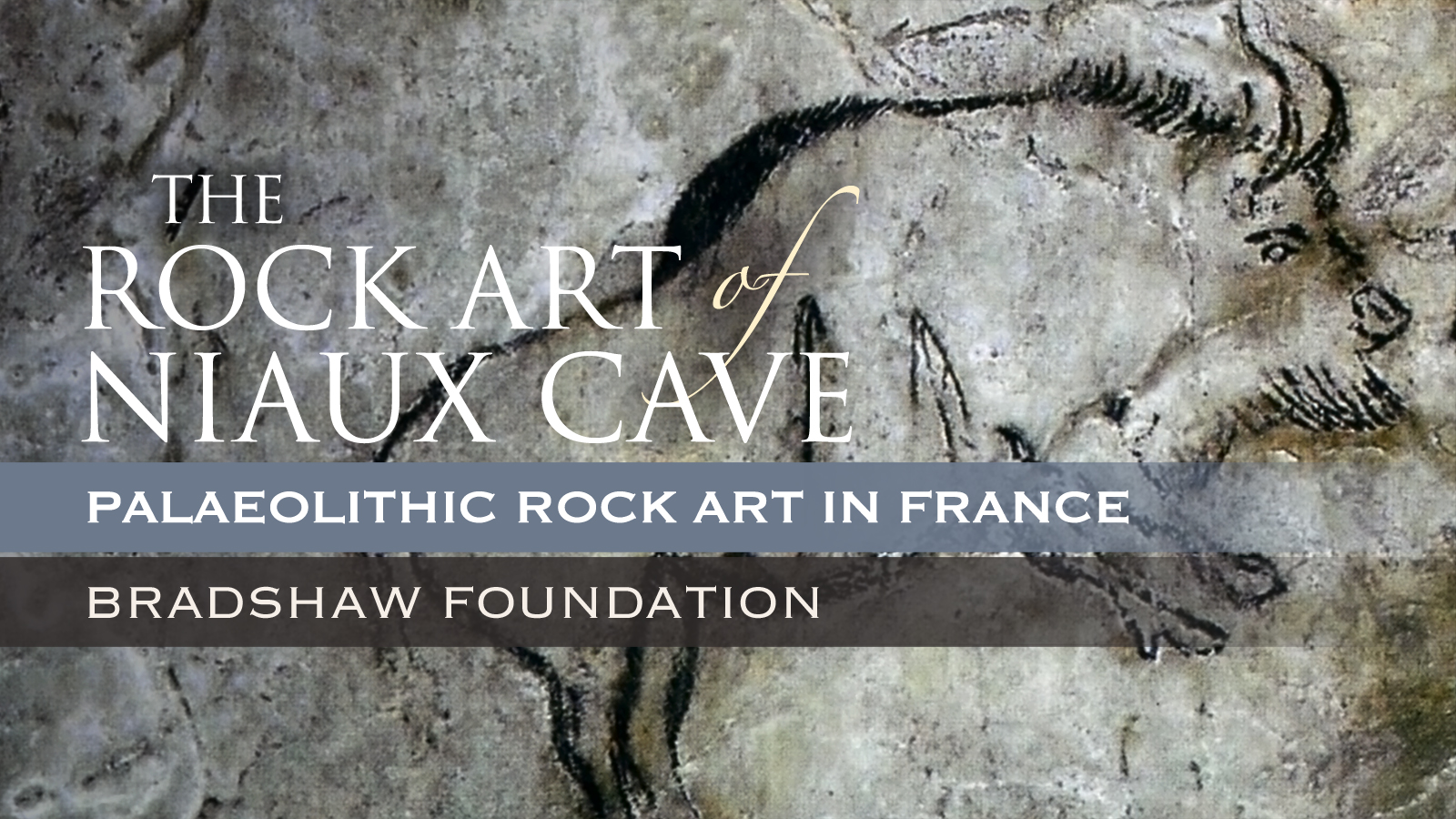

Niaux Cave has been visited since the 17th century - as shown by the graffiti, dated as early as 1602. The curiosity continued in to Victorian times when considerable plundering of its stalagmites took place. It was not until 1906, once the cave paintings in the main chamber of the cave - Salon Noir - were acknowledged as prehistoric, that the preservation of the cave and the study of the paintings began. Now, through radiocarbon dating of the charcoal, we know the rock art is at least 14,000 years old.

In June 2006, to celebrate the cave's centenary year, the Bradshaw Foundation helped fund an unprecedented exploratory project in the The Niaux Cave Complex. Pascal Alard, Director of the Niaux Cave, in association with the French Ministry of Culture, and guided by the world renowned and resident Dr Jean Clottes, supervised the draining of several lakes in the Niaux Cave complex, to temporarliy expose the Galerie Cartailhac - named after one of Niaux's earliest archaeologists - and the Reseau Clastres. This project would allow scientists for only the fourth time since prehistory to analyse the inaccessible parts of the cave and its contents, and a selection of the general public, to access those deep galleries for the first time ever.

The first scientific expedition of the Niaux cave in France, was in 1971 when Jean Clottes and Robert Simonnet, entered these unseen pristine chambers to study the cave paintings we now term Magdalenian parietal rock art, after spelunkers had first emptied the siphons and discovered the new galleries. But as they were to discover, there was more than just the art.

It was in the Reseau Clastres that they came across the footprints, an unwitting legacy of the prehistoric people who had explored the Niaux cave millennia before. The scientists calculated that the prints belonged to children between the ages of 8 and 12. They were also able to establish that the central figure - perhaps older than the outer two - was slightly ahead, probably leading them.

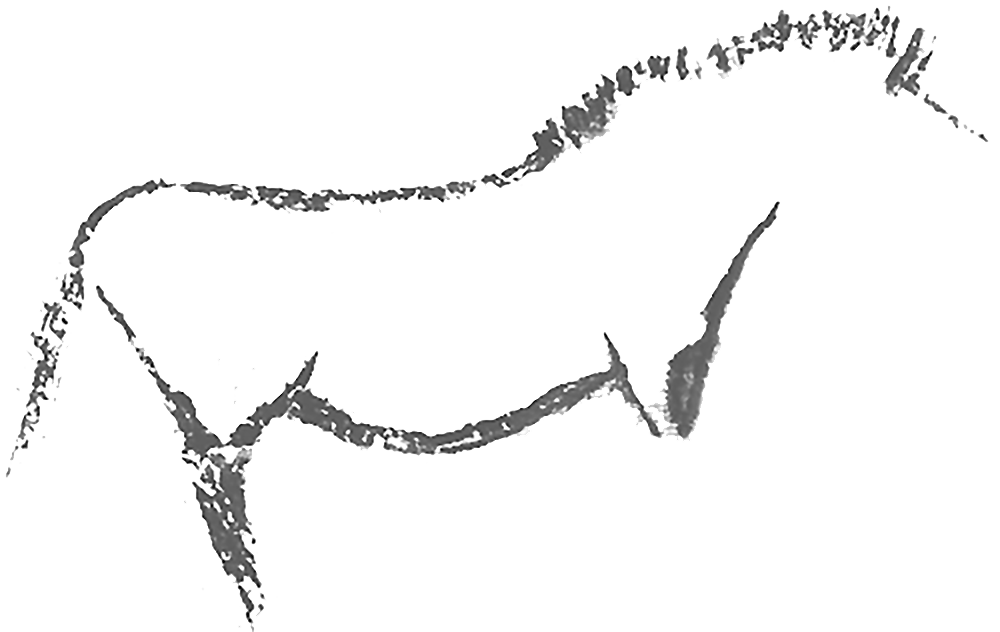

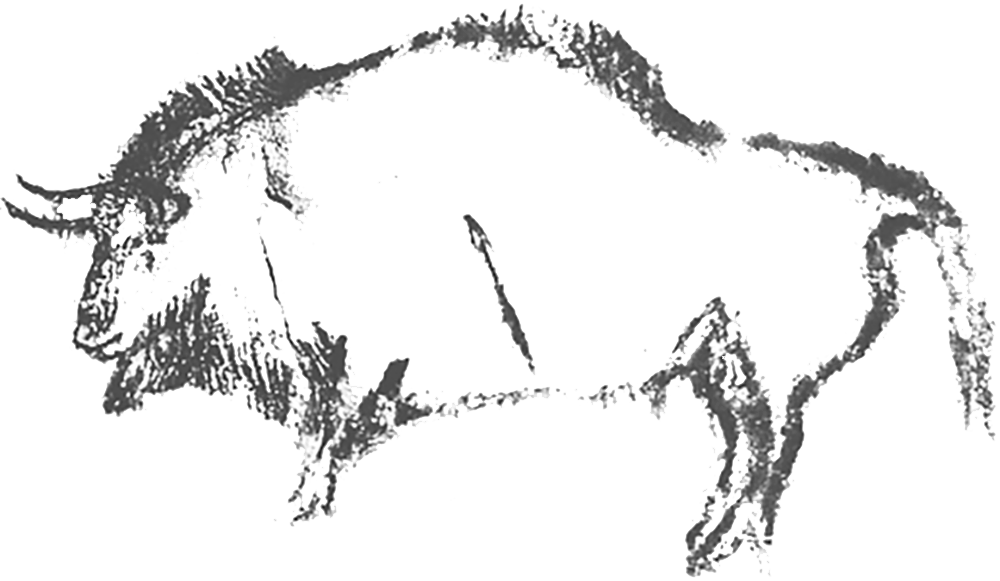

When the first spelunkers explored the cave now named Reseau Clastres, in a huge chamber they discovered charcoal drawings, small in number, but beautifully executed - three bison, a horse and a weasel. The weasel was of interest for 2 reasons; not only was this subject matter unique in prehistoric art, but the stylized sophistication of the drawing allowed Jean Clottes and Robert Simonnet to determine how the artist had executed it - in 10 bold and faultless strokes. It was a figure quickly made by an experienced artist.

After a disorientating amount of time underground exploring the newly exposed sections of the Niaux cave, the Bradshaw Foundation team made their way through the rest of the Niaux cave system.

The main entrance to Niaux leads into a large and even-floored cavern, wide and high-ceilinged. The cave walls are smooth and clear - and empty. For the first 400 metres there are no paintings or engravings; simply no rock art whatsoever. But at a particular point the open cavern becomes restricted, caused by an ancient collapse of enormous jagged boulders from the ceiling. As Jean Clottes remarked, one can continue into the cave by climbing with considerable difficulty over the debris, or squeeze through a narrow passage to the left. As one emerges from this, and on either side of the opening, the paintings begin - as symbols. Simple linear lines in red seem to mark the beginning of the painted cave, the beginning of the experience.

These enigmatic and understated decorations continue, with a hundred or so red and black geometric signs - dashes, bars, lines, and series of dots - some painted using tools, some using fingers. The red is hematite, the black is either manganese dioxide or charcoal, both ground and mixed with water or fat. Precisely what the symbols represent is hard to say, but they are not random. They have been daubed strategically, sometimes opposite each other, sometimes on either side of a conspicuous fissure.

One of the most tantalising symbols is the claviform. They are painted in red, and frequently found in this region of France and the the Pyrenees. They are all attributed to the Magdalenian epoch - 15,000 to 12,000 years before present. There are various interpretations - boomerangs, clubs, or axes, as the famed Abbè Breuil surmised. Or stylised female figures, according to the hypothesis of Professor Andrè Leroi-Gourhan. Or a time-unit, perhaps of a lunar month, which may explain why they seem to appear alongside the meticulously painted dots. However, the palaeolithic symbolism avoids modern cognitive computation, just as present-day Christian iconography - a religion represented by a baby, a virgin mother and a cross - might do for archaeologists in thousands of years in the future.

This chamber, where the smallest sound reverberates magnificently, is the largest and highest on the right side of the cave system. It seems to lie at the centre of Niaux's purpose. The Niaux cave paintings are not spread over the entire surface of the cave walls. Instead they are grouped together in separate, generally concave panels, composed of animals, mostly bison, ibex, horses and deer. As in the majority of Palaeolithic cave art paintings, these animals are represented in profile, without a base line, as if suspended in air.

The very end of the gallery is marked by a deer head above the alcove - here the artist recognized the shape of the head and only felt the need to draw on the antlers. This is a significant element of the sophistication of the rock art - in what would have been illuminated only by a flickering flame, the Palaeolithic artist would have seen animals - the back of a bison, the hind-quarters of a horse - and inspired by the very topography of the rock surface to paint a particular animal. It was as if the rock was telling the artist where to paint and what to paint, as if an animal-spirit was there in the rock, half appearing, literally at hand.

Near the deer head, other paintings adorn this sanctuary of the cave, but there is one further painting, deeper still, and accessible to the Palaeolithic artist only by crawling on hands and knees - an indeterminate painting, perhaps a human figure, or perhaps the hind legs of a deer-like creature that seems to be disappearing into the very rock itself. The fact that the ultimate painting in the cave - in the farthest recess - is mysterious, when compared with the other images in the Salon Noir, is most intriguing, and probably highly significant.

By studying paintings and engravings created during prehistoric times, we are afforded an insight in to the psyche of the Palaeolithic mind, into the psyche of our ancestors.

Rock art illuminates the sacred and ideological components of a culture which other archaeology may not. But unlike with the secure display cases of museums and the humidity-controlled art galleries of today, this unique opportunity is vulnerable - it is a delicate privilege, and both nature and mankind can cause their destruction at any time.

Caves are living creatures, sculpted by water over eons of time. The inertia of the cave - the quantity of energy required to change the conditions in the cave - is delicately balanced against the resilience of the cave - the time taken for these changes to revert to their initial state.

Water circulation shifts over time, exposing fresh walls to its eroding effects. The moment, or moments, that saw the creation of these paintings within this ephemeral context will not be static. An increase in water infiltration will affect the paintings, sometimes destroying them altogether. The lime content in the water that decorates this subterranean world can also be the agent of destruction, masking the paintings and drawings. Therefore, in an effort to control the cave's resilience, in Niaux, drainage systems - in effect artificial stalactites - have been installed above the paintings.

But the major contributor to a cave's inertia is humankind - the rock art is being jeopardized by its modern audience. Thankfully, since the early explorations in the 17th century, we now have a greater understanding of the lethal cocktail of heat, carbon dioxide and water vapour, but lessons have been learnt at a price. At the Lascaux Cave , after the ill-conceived installation of new climatic equipment, and with uncontrolled numbers of viewers, the cave suffered a fungal infection - Fusarium solani - that threatened to destroy in months what thousands of years had left largely unscathed.

For this reason, some caves have been closed to the public completely - Chauvet Cave is a prime example - it's wonders have been seen by less people than have stood on the top of Mt Everest. However, at Niaux a compromise has now presented itself in several ways.

The entrance now consists of a sealable access tunnel. Official guides take a limited number of groups with 20 people maximum in each into the cave for limited periods of time throughout the year. The climate of the cave is monitored on a 24 hours a day basis.

In the small French town of Tarascon-sur-Ariëge in the valley below Niaux, a virtual cave has been created at the impressive Park of Prehistory museum. With the latest technology in 3-dimensional topographic mapping and ultra-violet imagery sensing, the virtual cave shows every detail of the prehistoric art, more even than the visitors can see in the cave itself. Indeed, in the museum a virtual prehistoric world has been constructed, with re-enactments, film and museum displays. The most recent addition to the Park of Prehistory in June 2009 was the Jean Clottes Resource Center - Centre de Ressources Jean Clottes.

Dr. Jean Clottes stated that three years ago, he and his wife Renee, now sadly departed, decided to bequeath his life's work in prehistory - over 4,000 books, numerous journals, archives and reprints, and some 60,000 slides - to the Park of Prehistory. The collection of works are now being housed in a purpose-built documentation centre, named after the eminent prehistorian. To celebrate this, a new and extensive exhibition entitled 'The Art of Origins, Origins of Art' was planned to coincide with the Center's opening. Jean Clottes hopes that this will not only attract researchers, but that it will also encourage the donation of books, archives and even objects from both academics and members of the public.

The new International Center of Rock Art includes exhibition space of 500 sq.m., a 120-seat auditorium and a library. With this new development, the Park of Prehistory at Tarascon-sur-Ariege achieves 'museum' status.

Why did the Magdalenian people use the depths of the cave, and what meaning did they give to the inscriptions they left there? Studies have shown that the images were often superimposed - the successive layers of lines illustrate the contributions of successive artists. Why was this? Was the painting not complete? Or does it suggest that process was more important than product? This was a process that continued for a great length of time.

The themes depicted suggest that the paintings were not the expression of material, utilitarian or purely artistic preoccupations. Instead, the symbols and the animals represented expressions of a spiritual conception of existence. In a word - religion.

The fact that these paintings and engravings were made deep inside caves where nobody lived suggests they were endowed with spiritual significance. Man creates gods in his own image. At this time, Palaeolithic humankind was surrounded by animals, and therefore part of this faunal matrix, not above it.

Was it possible that the paintings represented this spiritual connection? If this is so, and based on our observations of modern hunter-gatherers in other parts of the world, we can hypothesize that these paintings were the work of shamans. Jean Clottes and David Lewis-Williams believe that the shamanic stance would suggest that the rock face in the cave is the 'veil' between the 'world' and the 'spirit world'; why else would an artist paint an ibex passing into the rock?

Shamanism has multiple components, but there are several fundamental features. A shamanic society believes in a cosmos in which several worlds exist. Shamans, in particular, have direct access to these other worlds - to cure, to maintain, to restore and to ensure. They may also receive spirit-helpers in animal form. Fluidity characterizes shamanism - fluidity between the different worlds, between the genders, between humans and animals. Clearly, this concept is a working and logical hypothesis. Not all palaeolithic rock art can be ascribed to shamanic practices, but this concept does help us take a step toward understanding our ancestors' attitude to the supernatural and their ways of approaching their own gods.

→ France Rock Art & Cave Paintings Archive

→ Chauvet Cave

→ Lascaux Cave

→ Niaux Cave

→ Cosquer Cave

→ Rouffignac Cave - Cave of the Hundred Mammoths

→ Bison of Tuc D'Audoubert

→ Geometric Signs & Symbols in Rock Art

→ The Paleolithic Cave Art of France

→ Dr Jean Clottes

→ Bradshaw Foundation

→ Rock Art Network