An article on washingtonpost.com by Sarah Kaplan - Scientists discover hundreds of footprints left at the dawn of modern humanity - reports on the Engare Sero footprints in northern Tanzania left by prehistoric people as they walked across the muddy terrain, leaving an indelible record of their presence pressed into the ground.

The Engare Sero footprints. Image: Liutkus-Pierce et al.

The site in northern Tanzania is the largest assemblage of ancient human footprints in Africa. It has been studied by geologist Cynthia Liutkus-Pierce and her colleagues, and reported in the journal Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. The 400-odd footprints, which cover an area the size of a tennis court, were imprinted in deposits from an ancient flood, dried, then covered up with a second layer of mud and preserved for as many as 19,000 years.

Ancient Engare Sero footprints of Tanzania #Africa #palaeontology #archaeology https://t.co/5lZncVJ8Wy pic.twitter.com/ueqxIST8IO

— Bradshaw Foundation (@BradshawFND) October 13, 2016

Now excavated, anthropologists at the site plan to use the footprints to understand social dynamics at the end of the Pleistocene era, a time when the climate was changing and Homo sapiens was on the brink of sedentary behaviour.

Briana Pobiner, a paleoanthropologist at the National Museum of Natural History and a member of Liutkus-Pierce's team, claims it will provide a sense of the group size and structure of these ancient hunter-gatherers; the composition of this group, how many males, how many females and children, how many directions, running, walking, walking side by side, and so forth.

Snapshot in time - most knowledge about ancient communities is reconstructed from exhumed skeletons, scattered tools, animal bones dug up from bygone garbage pits. But the Engare Sero prints have the potential to tell us exactly who lived in this spot, how they related to one another and where they may have been headed.

The site was discovered by a resident of the nearby village of Engare Sero about a decade ago, but the scientific community, involving colleague Jim Brett, didn't learn of the prints until 2008.

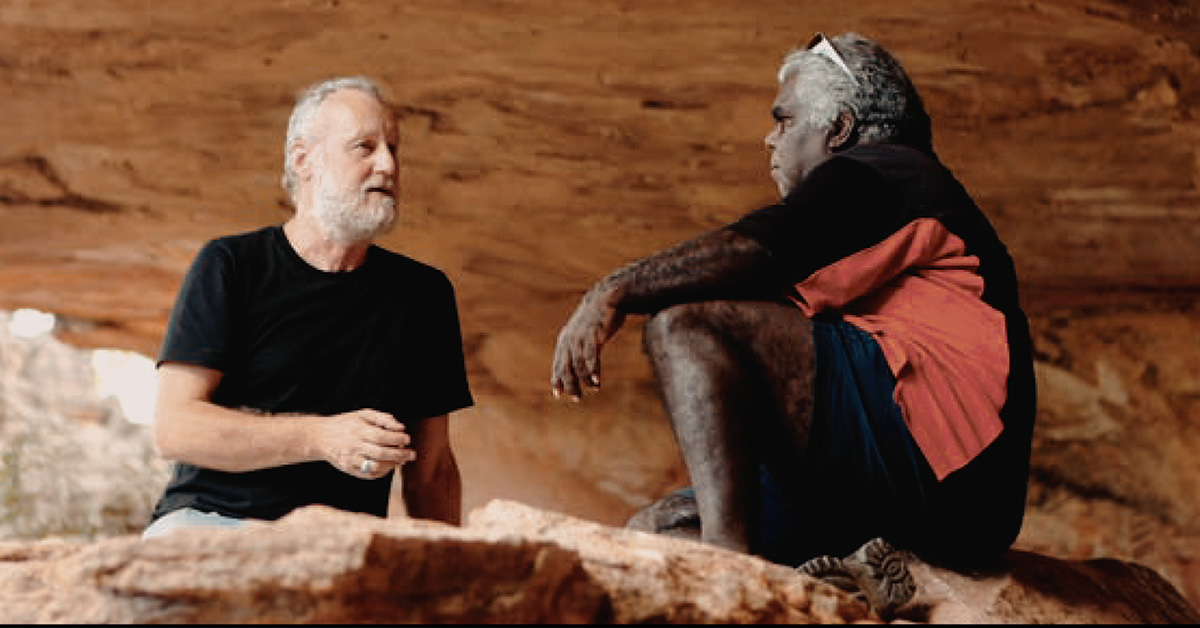

Engare Sero villagers examine the footprints. Image: Cynthia Liutkus-Pierce.

With a grant from the National Geographic Society, Liutkus-Pierce assembled a team of geologists, archaeologists and anthropologists to excavate the site. Their discovery was first reported by National Geographic recently. They worked to expose the rest of the prints, elucidate their origins, document their context and interpret their significance. Each print was photographed and 3-D scanned. Soil samples were sent off to labs for radiometric analysis.

When researchers first arrived at Engare Sero, they thought that the site might be hundreds of thousands of years old. The Laetoli footprint trails discovered by paleontologist Mary Leakey and Paul Abell are just a few dozen miles away; those impressions were made by two Australopithecines walking through volcanic ash 3.6 million years ago.

Dating the rock layer - the volcanic ash around the footprints appeared to be 120,000 years old, yet other dated materials yielded ages that were much younger. Efforts to date plant material embedded alongside the prints proved futile. Eventually, Liutkus-Pierce and her team concluded that the mud must have been deposited during a flooding event, rather than a volcanic eruption. But since floods jumble materials of different origins and ages together, that meant the scientists had to date dozens of different minerals. The youngest crystal in the footprint layer would represent the oldest possible age for the prints; the oldest crystal in the layer above it would represent the youngest they could be.

Using the argon-argon dating technique, by which scientists measure the decay of an isotope called Argon-40 into Argon-39 in order to find the age of crystals, the team came up with a rough approximation of the footprints' age: 19,000 years at the oldest, 10,000 or 12,000 years at the youngest.

Hatala, a paleoanthropologist at Chatham University, is part of a subset of the Engare Sero team looking at the anthropological aspects - examining the size and composition of the group that made them. The researchers have distinguished at least 24 distinct trackways (series of steps that can be attributed to a single person) going in two directions. They've established the age and genders of some of the footprint-makers, and established who was walking and who was running.

For part of their research, the team invited volunteers to match their own feet to the prints and attempt to follow the tracks, including residents of the nearby village - quite literally following in the footsteps of their ancestors.

Visit the ORIGINS section:

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 25 June 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 09 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 03 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 28 October 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 February 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 28 November 2019

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 October 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 25 June 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 09 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 03 November 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 28 October 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 23 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 04 June 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 14 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 May 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 February 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 20 January 2020

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 28 November 2019

Friend of the Foundation