Stone Tools in the Fossil Record

To understand the importance of Palaeolithic stone tools in relation to the Fossil Record, the Bradshaw Foundation spoke with Cassandra Turcotte of the Center for the Advanced Study of Hominid Paleobiology [CASHP] of George Washington University. What could the study of the Lower and Middle Palaeolithic lithic technologies - the earliest instances of innovation - reveal about the cognitive and symbolic processes involved? Are stone tools the first signs of creative behaviour?

Cassandra M. Turcotte

Center for the Advanced Study of Human Evolution

Center for the Advanced Study

of Human Evolution

George Washington University

First coined by Louis Leakey in 1936, the Oldowan is a term used to describe the earliest evidences of the human fossil record. Beginning 2.5 million years ago and restricted to Africa (de la Torre, 2011), the Oldowan industry can still be found in the form of similar flake tools in hunter-gatherer societies across the world today, even if it has been largely replaced by more advanced technologies. Leakey named this archaeological culture after the first area in which he documented it - the now-famous site of Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, Africa (Schick and Toth, 2006). His wife, Mary Leakey, published the first comprehensive work on the pair's finds at Olduvai in her book Olduvai Gorge Volume 3: Excavations in Beds I and II, 1960-1963 (Schick and Toth, 2006). This work is notable because it recognized the first instances of tool-making in human history, separated the Oldowan from the later Acheulean, and gave description to these earliest artifacts.

The Oldowan represents the first instances of technological innovation in human history, wherein our ancestors first began to enhance their biological abilities with the manufacture of stone tools. This speaks to an important milestone in the evolution of our ancestors. Tool production and use is thought to be intimately linked to, if not the instigator of, major changes in cognitive development; geographic ranges; and morphological features like body and brain size (de la Torre, 2011; Schick and Toth, 2006). Although the exact nature of these relationships remains contested, better understanding of these issues will inform our state of knowledge on subjects from the evolution of human cognitive sophistication to the timing of our genus' first use of fire or hunting.

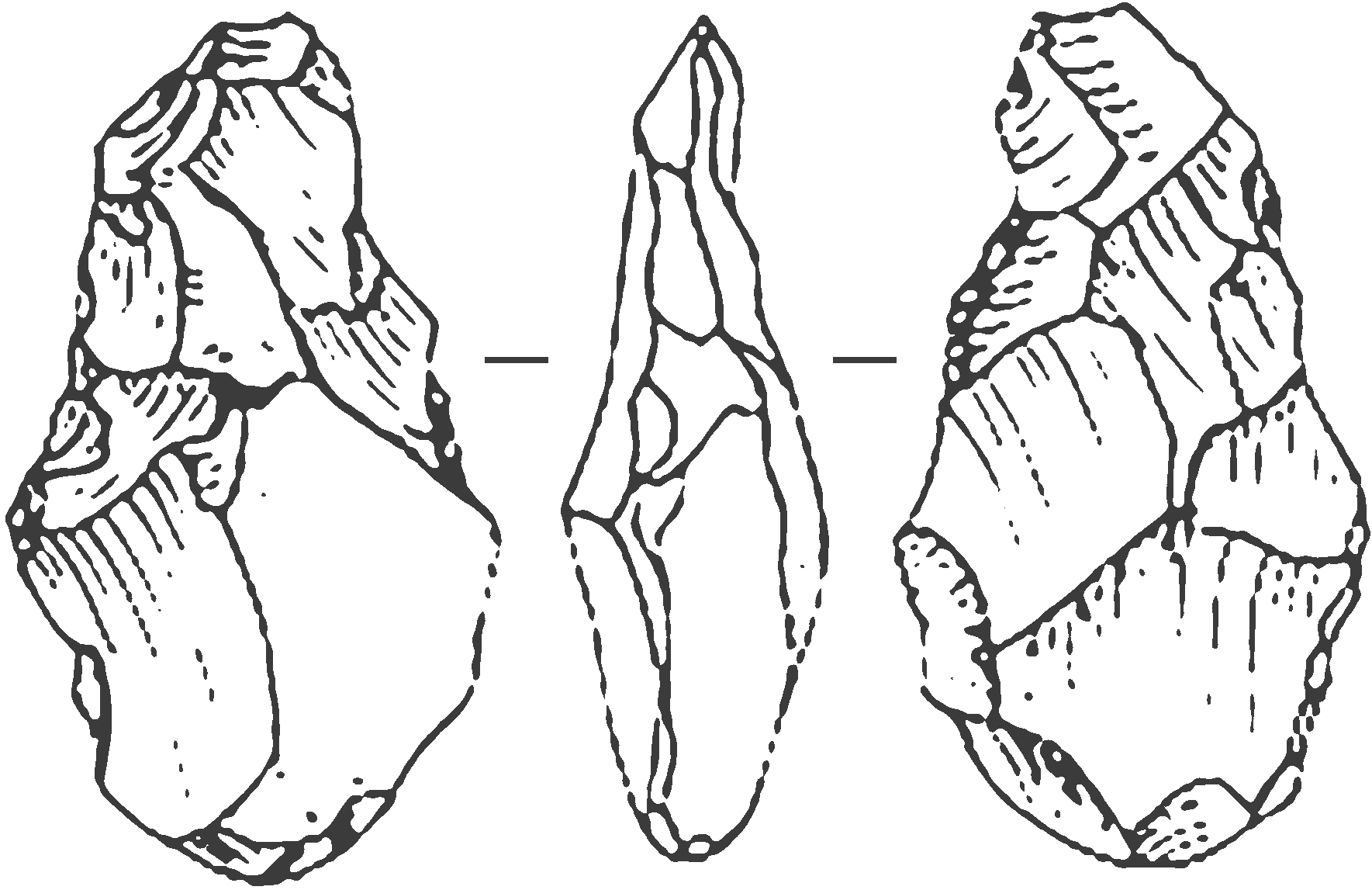

This technocomplex is characterized by a limited variety of simple artifacts, such as flakes; hammerstones; and cores with very little, if any, evidence of retouch. Hammerstones represent the usually fat, round stone one holds when percussing the stone of interest. Hitting this block at the right angle with high-impact will produce a thin, flat flake patterned with conchoidal fracture and a bulb of percussion. What remains of the block used to produce the flake is called a core (Kimura, 2002; Schick and Toth, 2006). Flakes can be categorized in a number of ways (i.e., chopper or scraper) depending on their morphology but all are distinct from natural stones from the artifacts of their manufacture (fracture lines, bulbs of percussion). The classification system of flake technology has itself changed much over the years, owing to debate between the Leakeys; Dr. Nicholas; and renowned French Acheulean archaeologist Dr. Francois Bordes (de la Torre, 2011; Kimura, 2002; Schick and Toth, 2006). In comparison to the Acheulean technologies, the Oldowan may seem relatively simple. This does not mean it represents anything less important. Rather, Oldowan technologies illustrate a graded development of stone tool complexity in the archaeological record.

The first instances of Oldowan tool technology crop up in Eastern Africa around 2.5 million years ago, following a period of global climate cooling and drying. As a result, African geography had changed quite a bit, with grasslands becoming predominant (Kimura, 2002; Schick and Toth, 2006; Stout et al., 2005). Interesting changes were also happening to the several branches of the human lineage alive at that time, with the advent of robust australopithecines and our own genus, Homo. Thus, the candidates for the inventors of the Oldowan are many. There are the gracile australopithecines,

Australopithecus afarensis (3-2.2 myr) and

Australopithecus garhi (2.5 myr) as well as the robust

Paranthropus aethiopicus (2.5 myr),

Paranthropus boisei (2.3-1.2 myr), and

Paranthropus robustus (2-1 myr). This time period is also recognizable for the beginning and diversification of our genus, with

Homo habilis (2-1.6 myr);

Homo rudolphensis (2.4-1.7 myr) and

Homo ergaster/

Homo erectus (1.8 - 1 myr) existing in temporal proximity to each other (Schick and Toth, 2006).

All but Au. africanus were dated to the same time period as nearby Oldowan sites (Schick and Toth, 2006). Unfortunately, few fossil remains are directly associated with Oldowan technology in the archaeological record. In one instance of this at the Olduvai Gorge site FLK, both

Paranthropus boisei and

Homo habilis were found in direct association with stone tools. Indeed, many mammals were found in direct association with the Oldowan technology (Schick and Toth, 2006). A specimen of early Homo, STS 53 from South Africa, exhibited a cut-mark that could have been from a stone tool, although whether early Homo made the cut remains yet another uncertainty (Schick and Toth, 2006). Even instances of direct association can be difficult to decipher and we must seek out other sorts of evidence.

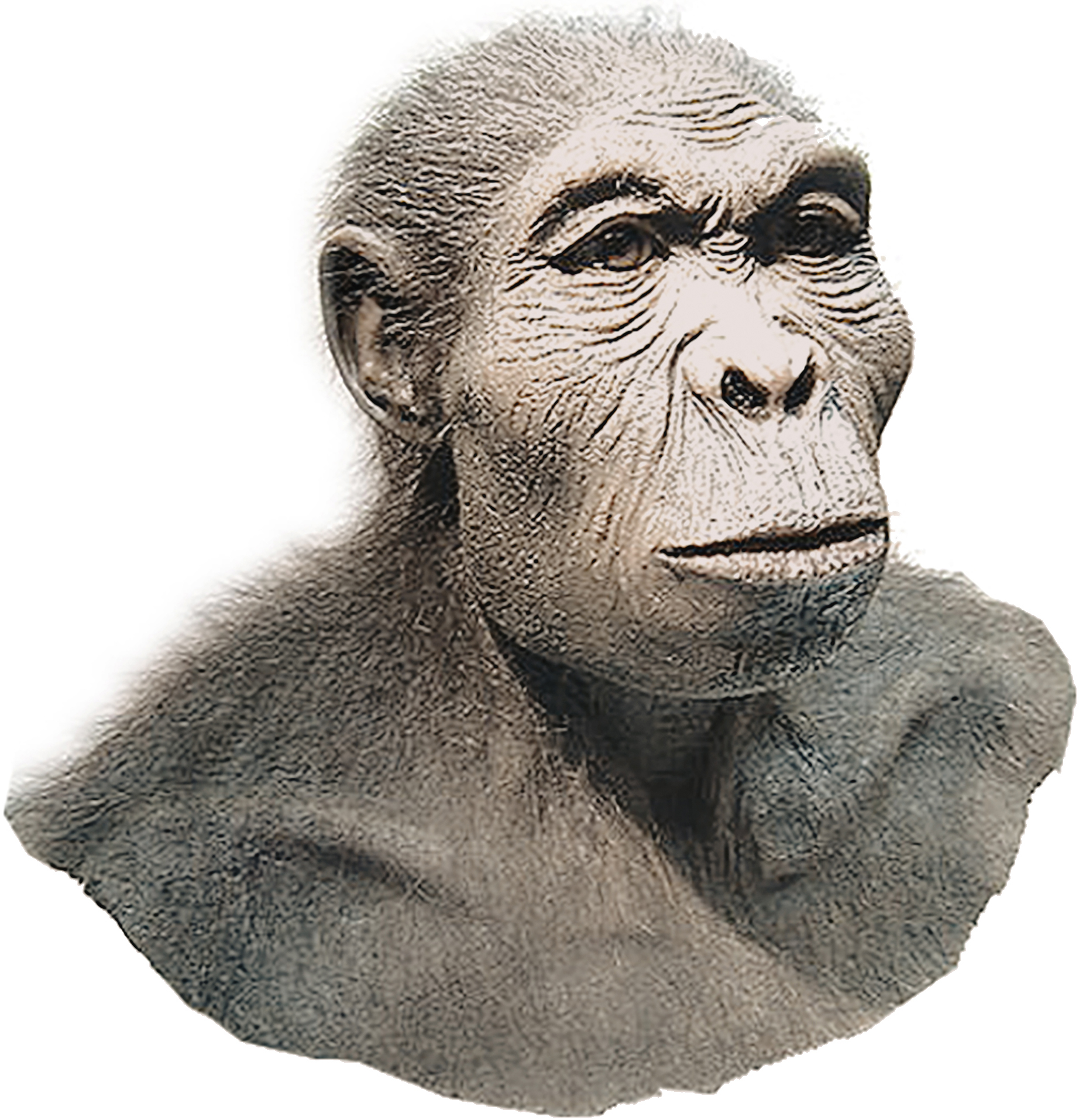

Initially, having worked at FLK, Mary Leakey proposed that

Homo habilis was responsible for the tools rather than

Paranthropus boisei (Schick and Toth, 2006). This supports the timeline for relating stone tool production the increase in brain size, and remains a popular hypothesis in current paleoanthropology (Schick and Toth, 2006). Other researchers, like Susman (1991), suggest that the robust australopithecines were more likely the producers of the Oldowan out of necessity. Very simply, the robust australopithecines needed to process very tough plant resources, a task Susman (1991) claims would have required tools. Susman (1991) supports this idea with the assertion that Paranthropus' hand morphology was adapted for precision grasping. Given the contemporaneous nature of the hominid species at that time, it's possible that any one up to all of them had some part to play in the shaping of the Oldowan. In spite of that possibility, it's known that only one genus survived past 1 million years ago: Homo.

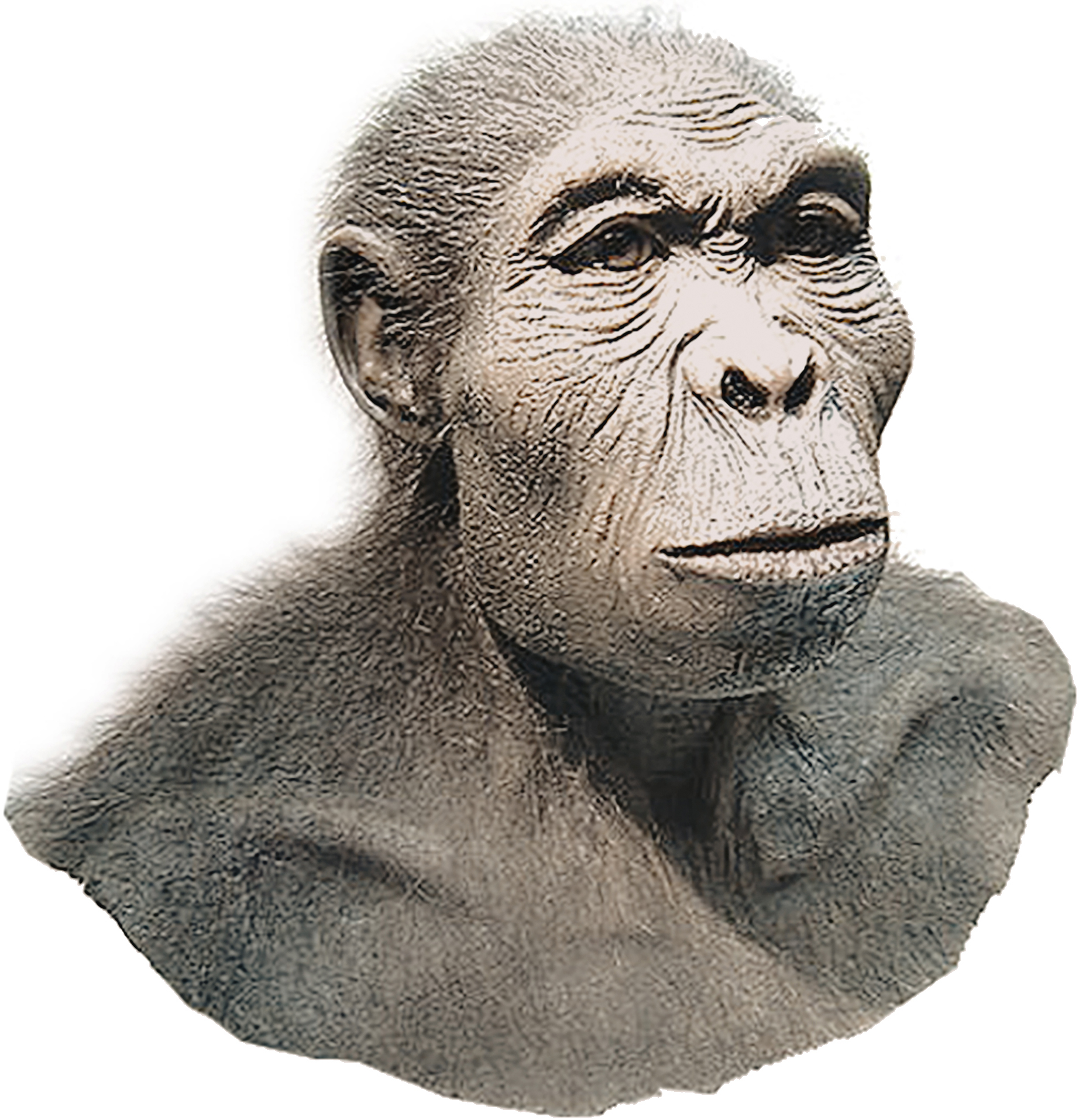

Reconstruction of Homo habilis

In addition to who could have made it, the question of the Oldowan's functionality also remains largely unknown. This problem contributes to a larger debate about the nature of early human meat acquisition - was it hunting, or was it scavenging? The precise use of the tools can't, of course, be determined, but experimental functional studies have gone a long way in the description of functional features (Schick and Toth, 2006). This boils down to whether hominids had primary access (hunting) or secondary access (scavenging) to carcasses and deals with the requirements of each scenario (Dominguez-Rodrigo et al., 2004). Primary access gives predators a better selection of most nutritive meat, for example. Schick and Toth (2006) argue that this mode of meat acquisition would not necessarily require the kinds of processing that secondary access would, wherein the marrow inside bone would represent the best-value resource (see also Dominguez-Rodrigo et al., 2004). Therefore, bones with percussive damage or fracturing would more likely be attributed to secondary access. This particular debate has not yet been resolved.

Contributing to this problem are speculations that our cousins, the chimpanzees, could have produced these materials as well. Once thought to have extremely primitive cognitive and technological abilities, chimpanzees are now observed to make and use tools for a number of tasks (Goodall, 1986; Schoning et al., 2008; Schick and Toth, 2006). In chimpanzee tool making, however, their chosen materials are often organic, leading to decreasing likelihood of preservation (Toth and Schick, 2009). These tools include items such as long, stripped sticks used for termite fishing (Schoning et al., 2008). Additionally, chimpanzees also use stone tools, often in the form of hammers and anvils for the cracking of nuts (Toth and Schick, 2009). While some researchers argue that the stone artifacts from such activity are comparable to Oldowan lithics, others claim the battered, fractured stones don't really represent the type of careful, thought-out knapping exhibited by the Oldowan tools (Toth and Schick, 2009). In experimental studies, African apes like bonobos have been trained to successfully produce Oldowan-like tools, but less skillfully (Schick and Toth, 2006). The possibility of chimpanzee toolmakers, however, brings up another controversy - that of the Pre-Oldowan.

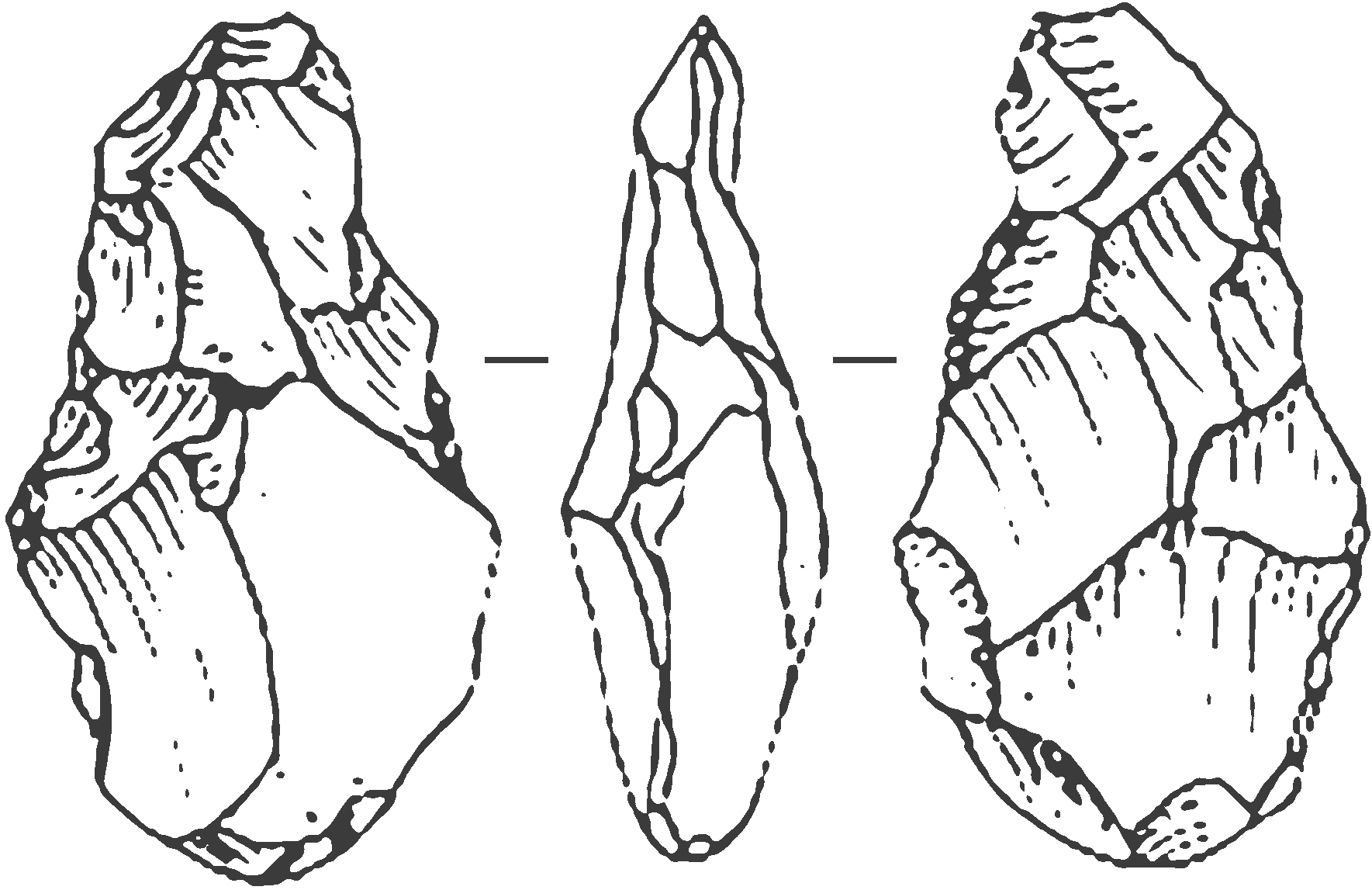

Oldowan Chopper

José-Manuel Benito Álvarez CC BY-SA 2.5

The Pre-Oldowan is a term given to tools older than 2 million years at sites like Gona, Ethiopia and West Turkana, Kenya, which seem to exhibit less skill than we expect from the traditional Oldowan (Schick and Toth, 2006). It's true that these sites seem to exhibit fewer instances of retouching, which becomes more prevalent after 2 myr at Olduvai and East Turkana (Schick and Toth, 2006). Recent studies have shown, however, that even among the oldest sites flakes do indicate high levels of skill. For example, at Gona, Ethiopia, material dated to 2.5-2.6 myr represented skillfully flaked lava cobbles (Schick and Toth, 2006; Semaw, 2000). Gona and its associated site Bouri also showed evidence of raw material selectivity, with a preference for felsic volcanic rocks as opposed to the mafic basalt common to Olduvai and Koobi Fora. This indicates a clear hominid preference for fine-grained and phenocryst-poor rocks more suitable to flaking as well as the ability to plan ahead for future tool production (Stout et al., 2005). Evidence suggests that skillful flaking and forethought were components of human tool production even as early as 2.5 million years ago, quite contrary to the concept of the Pre-Oldowan, although this conclusion is still in contention.

It's hard to know much about a world and its inhabitants so far into the past, but we can make tentative steps in this direction using archaeological material. In the case of human behavioral evolution, the first evidence that we have come in the form of simple stone tools that we've categorized as the Oldowan. Simple flakes, cores and hammerstones that could be mistaken for natural to an untrained eye give us insight into lives and needs of our ancestors. From hunting/scavenging behavior to the advancement of cognition, these tools provide an enigmatic window into the past. These debates are still ongoing, showing quite clearly the contentious nature of making functional conclusions about artifacts we don't completely understand. There are plenty of things still unknown about the Oldowan, even up to who first made or used them, but endeavoring to discover more about these tools contextualize later technocomplexes and help inform researchers in their debates about cognition, behavior, and the evolution of human technological innovation.

The Acheulean is a technological tradition characterized by an incredibly long history in the human cultural record across unprecedented geographical spans. First described in the 19th century by Gabriel de Mortillet and named for the French town of Saint-Acheul, the Acheulean uniquely includes the first appearance of the bifacial tool known as the handaxe (Wood, 2011). Two perspectives paint this technocomplex as either a great leap in human cognitive abilities and technological prowess or a long period of technological stagnation.

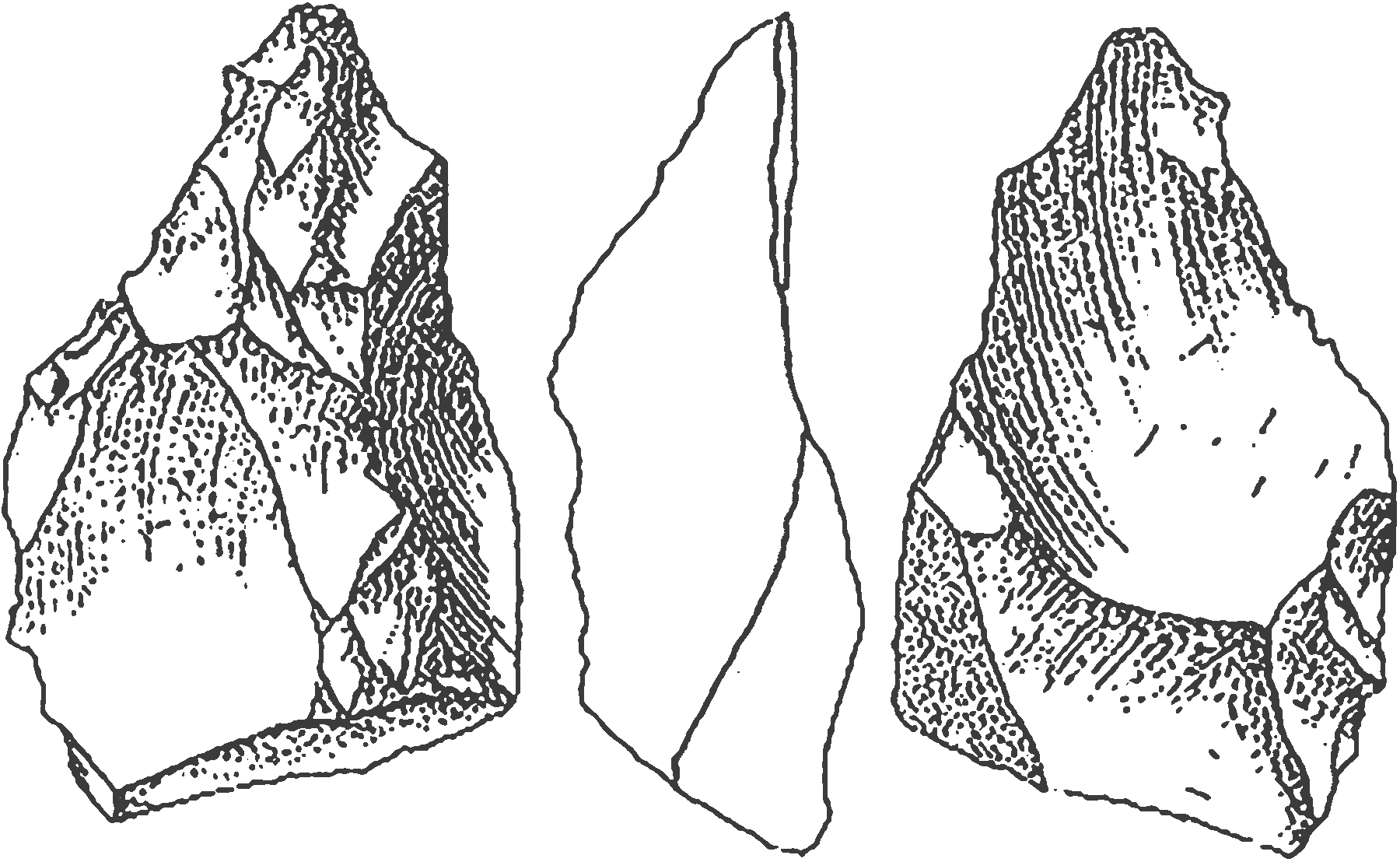

Early Acheulean handaxe from Sterkfontein Cave

The Acheulean industrial complex consists of flakes, retouched flakes and, most notably, bifacial tools (Clark, 1994). The earliest sites containing Acheulean technology come from East Africa up to 1.6 myr and terminate 200 to 100 kyr, making this an incredibly long-lasting technological industry (Clark, 1994). For a long time, the oldest known occurrence of the Acheulean was from Olduvai Gorge at the EF-HR site dated to 1.4 myr. This site had no associated human remains (Clark, 1994). This changed in 1992, when Asfaw et al. (1992) published their report on discoveries made at Konso-Gardula in the southern Main Ethiopian Rift (Clark, 1994). With Acheulean artifact-rich sediments spanning 1.3-1.9 million years, this discovery pushed the first appearance datum of this technological tradition up to almost half a million years and tied the tradition to

Homo erectus, thanks to hominid dentition and a mandible also discovered at the site (Asfaw et al., 1992).

Other early occurrences of the Acheulean include the appearance of handaxes and cleavers at Sterkfontein in association with calvaria from

Homo habilis dated to 1.6 myr and a few sites in northern Africa, including Sidi Abderrahman in Casablanca and Tighenif in Algeria, both from .7 myr. The Acheulean even makes it out of Africa into the Jordan Valley site of 'Ubeidiya by 1-1.4 myr (Clark, 1994). In many of these sites, including at 'Ubeidiya and Konso-Gardula, the link to

Homo erectus is clear and this species is now associated as the maker and user of the early Acheulean technologies.

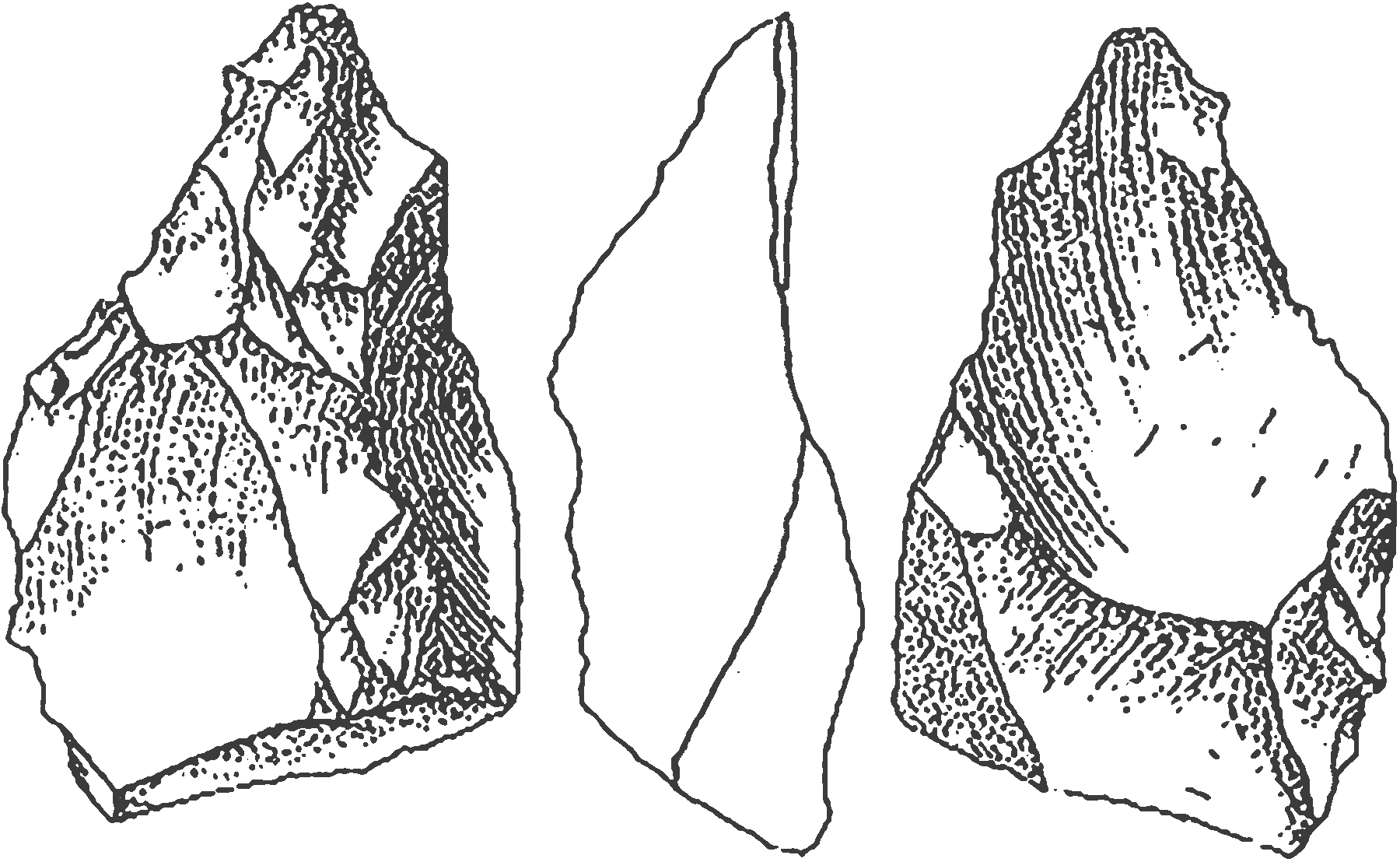

Early acheulean biface from Gona, Ethiopia

The geographic expanse of the Acheulean includes Africa, the Near East, India and parts of Europe, although it does not penetrate into Asia. These distributions have given rise to the notion that the Acheulean (or 'Mode 2') technologies arose in Africa and were brought into Europe and on to India via the dispersal of hominins, particularly the

Homo erectus with which the early Acheulean is associated (Lycett and von Cramon-Taubadel, 2007). Indeed, this conclusion finds general support from chronological data and experimental hypothesis-testing conducted by Lycett and von Cramon-Taubadel (2007), in which they modeled dispersal pattens in conjunction with transmission of Acheulean technology. They reiterate that Acheulean technologies developed in Africa and dispersed from that center of origin into Europe, the Middle East and India with repeated bottlenecking events.

Interestingly, the Acheulean failed to permanently penetrate much of Asia and the boundary dividing the parts of Asia with and without handaxes was termed the 'Movius' line. The archaeologist for which the line was named, Movius, determined that this was because Asia was a continent of cultural stagnation. Other researchers have variably attributed the absence to availability of organic tools (i.e., bamboo shoots) or the continued use of Mode 1 technologies in eastern Asia while Europe, Africa and the Asian subcontinent moved on to the Acheulean (Lycett and Bae, 2010). Eventually, Acheulean-type technologies were discovered in eastern Asia, although always at low frequencies. Such sites include the Hantan River Basin in Korea and in the Bakosa Valley in Indonesia, where handaxes are found at higher frequencies but mostly less than 5 percent of the assemblage. Lycett and Bae (2010) propose five explanations for the possible low frequency, including the possibility that human dispersal into eastern Asia came before the innovation of the Acheulean. Evidence of hominins in eastern Asia begins at sites like Yuanmou in southern China, Majuanggou in northern China and Sangiran in Indonesia. Dates for these sites, though controversial, go up to 1.8 myr, which means that hominins might have been there before the hominins in Africa first produced Acheulean-type tools (Lycett and Bae, 2010). There are also raw material constraints, the possibility of geographical and topographical barriers, the issue of bamboo availability and questions of social transmission. In short, there are many reasons why the Acheulean never made a big splash in eastern Asia, although it certainly made it to the rest of the Old World and stayed there for over a million years.

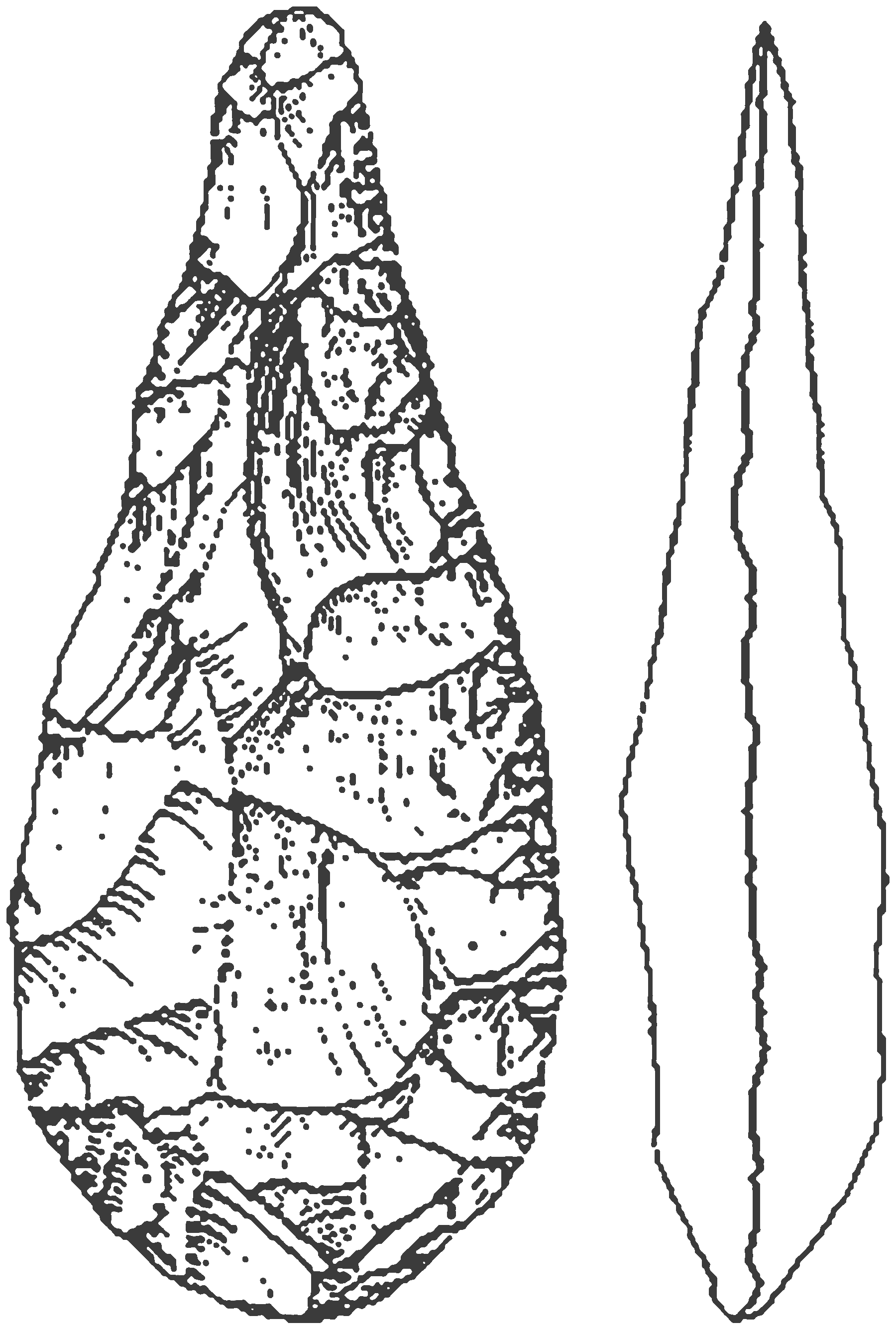

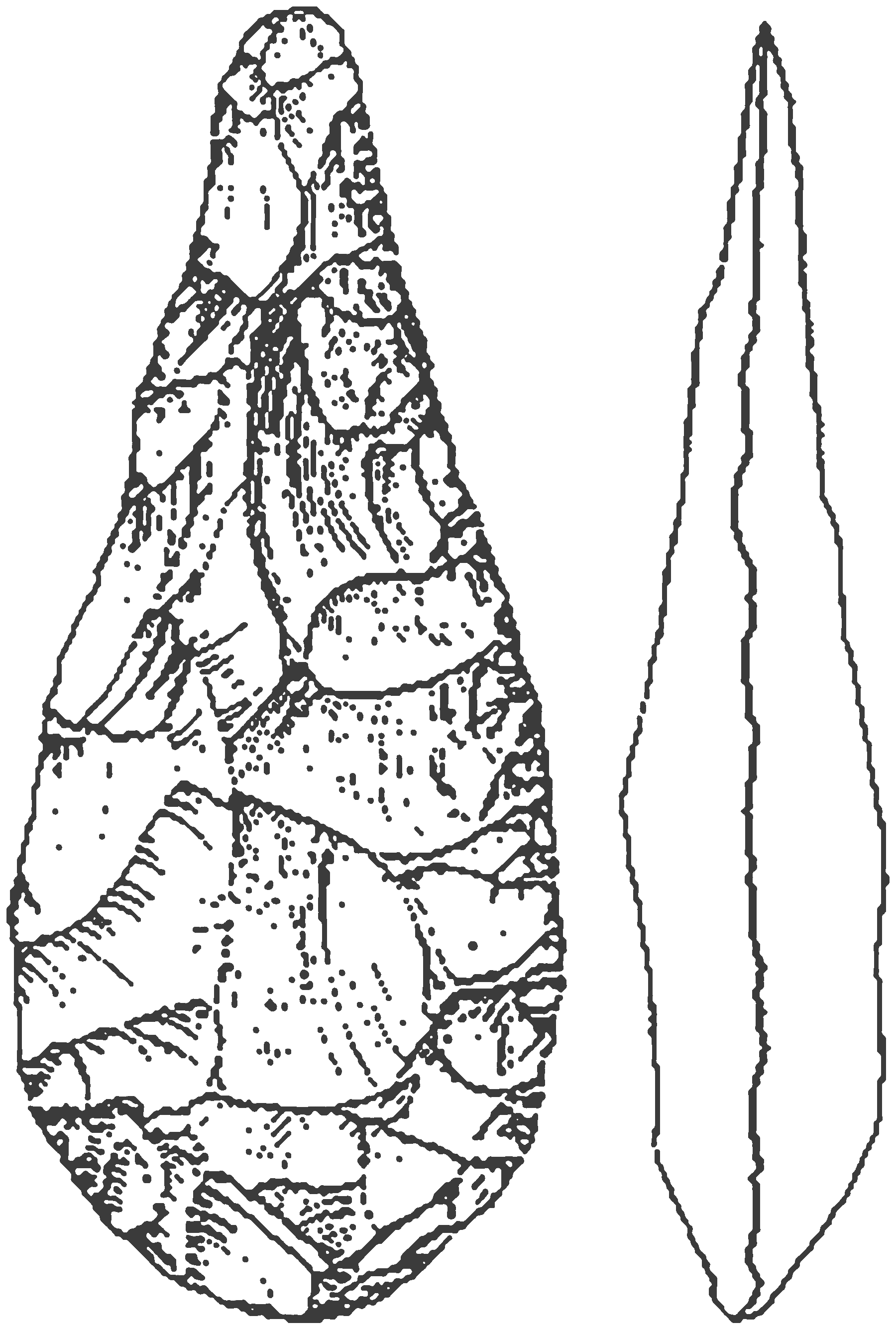

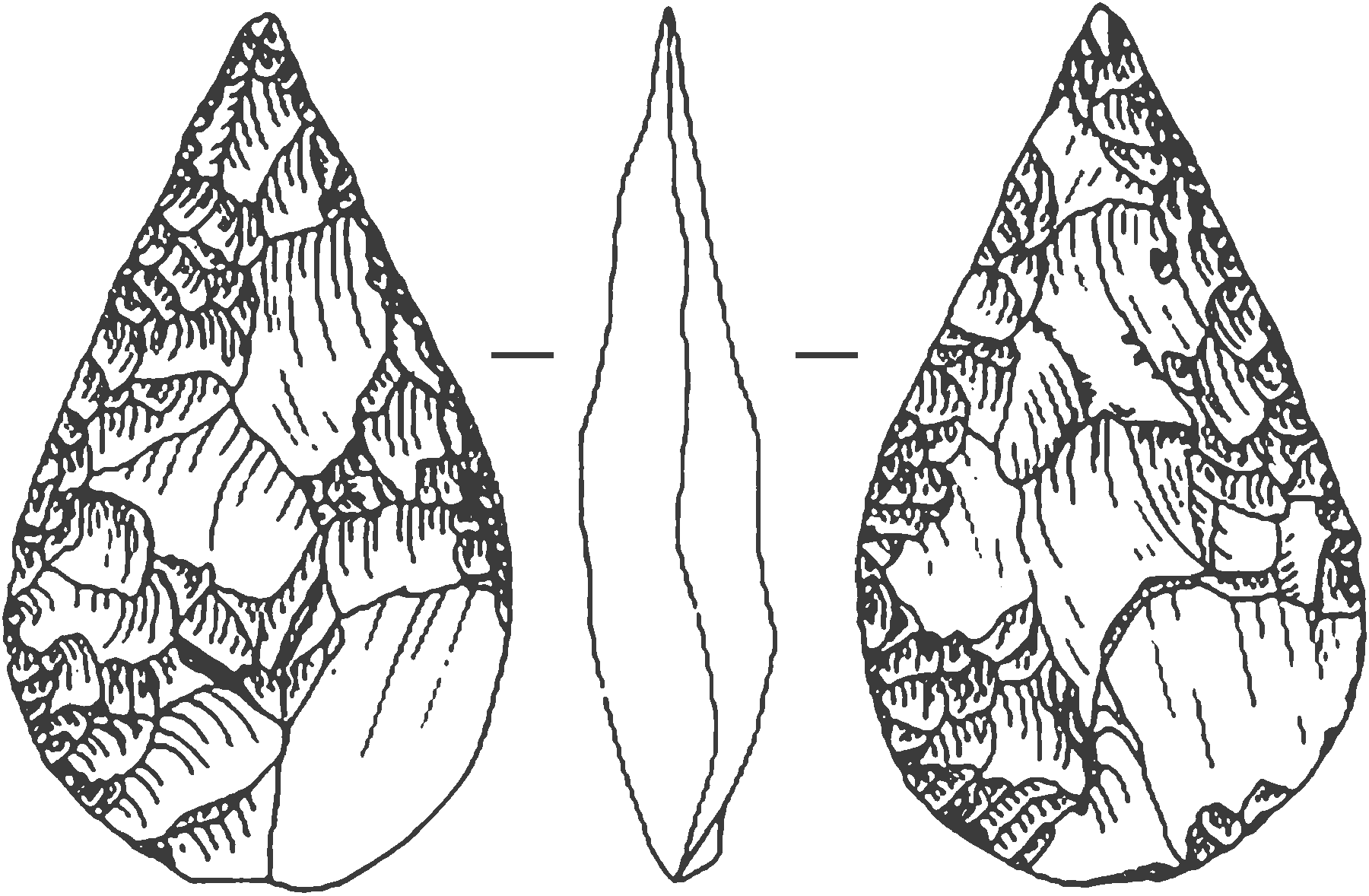

An Acheulean handaxe, Haute-Garonne France

The Acheulean itself is an important development in the history of human evolution, as this more advanced form of stone tool production purportedly indicates a leap forward in cognitive abilities. The handaxes themselves were used to process game and their production requires both long term planning, forethought, adaptability and understanding of the material to achieve the desired end result (Goren-Inbar, 2011). The handaxe is a raw material upon which a hominin has imposed a formed, a '[reflection of] shared mental templates' (McPherron, 1999). It is argued that variations through time in terms of morphology may then be interpreted as changes in cognition, although researchers like McPherron (2011) contend that shape actually only reflects more basic factors like raw material or reduction intensity (see also Archer and Braun, 2009). Indeed, Lycett and Gowlett (2008) suggest that the uniformity in the Acheulean Bauplan over such large expanses of geography an time indicate that the technology was under the pressure of strong functional constraints or, variably, cultural influence. McNabb et al.'s (2004) study questioned whether the Acheulean actually required social learning and found that 'cultural templates did not dictate the specific appearance of large cutting tools' at their sample site. Other archaeologists insist that the Acheulean signals cognitive advancement and stylistic variation, rather than mechanical constraint.

Ovate acuminate handaxe from the later Acheulean

For example, in Goren-Inbar's (2011) study, the author analyzed an ethnographic study of flint-knapping populations of the Irian Jaya, who produced bifaces from volcanic rocks. The process of production of bifaces was observed to require long-term memory, spatial or procedural cognition, advanced planning, and procedural 'know-how' or social cognition. Other research takes a neural approach, contending that higher order cognitive function is tied to motor action and that these processes must be in synchrony in order to make an Acheulean tool (Stout, 2011). According to Wu et al. (2011), Homo erectus endocasts suggest that these species may have had selective enlargement of neural areas relevant to tool-making cognitive processes. Thus, the Acheulean actually could signal both innovations in social cognition and technological creativity, although this conclusion is currently under debate.

Whether or not the morphology of the Acheulean tradition was determined by material or mental template, there's no denying that the lives of hominins during those million and a half years was anything but stagnant. This interval saw the rise of genus Homo and the decline of the australopithecines, periods of climate change and environmental variability, dispersals within and out of Africa, and numerous behavioral adaptations. One of the most famous of latter include advances in foraging strategies. That is, it's during this period that we first see definitive evidences of hunting and fire.

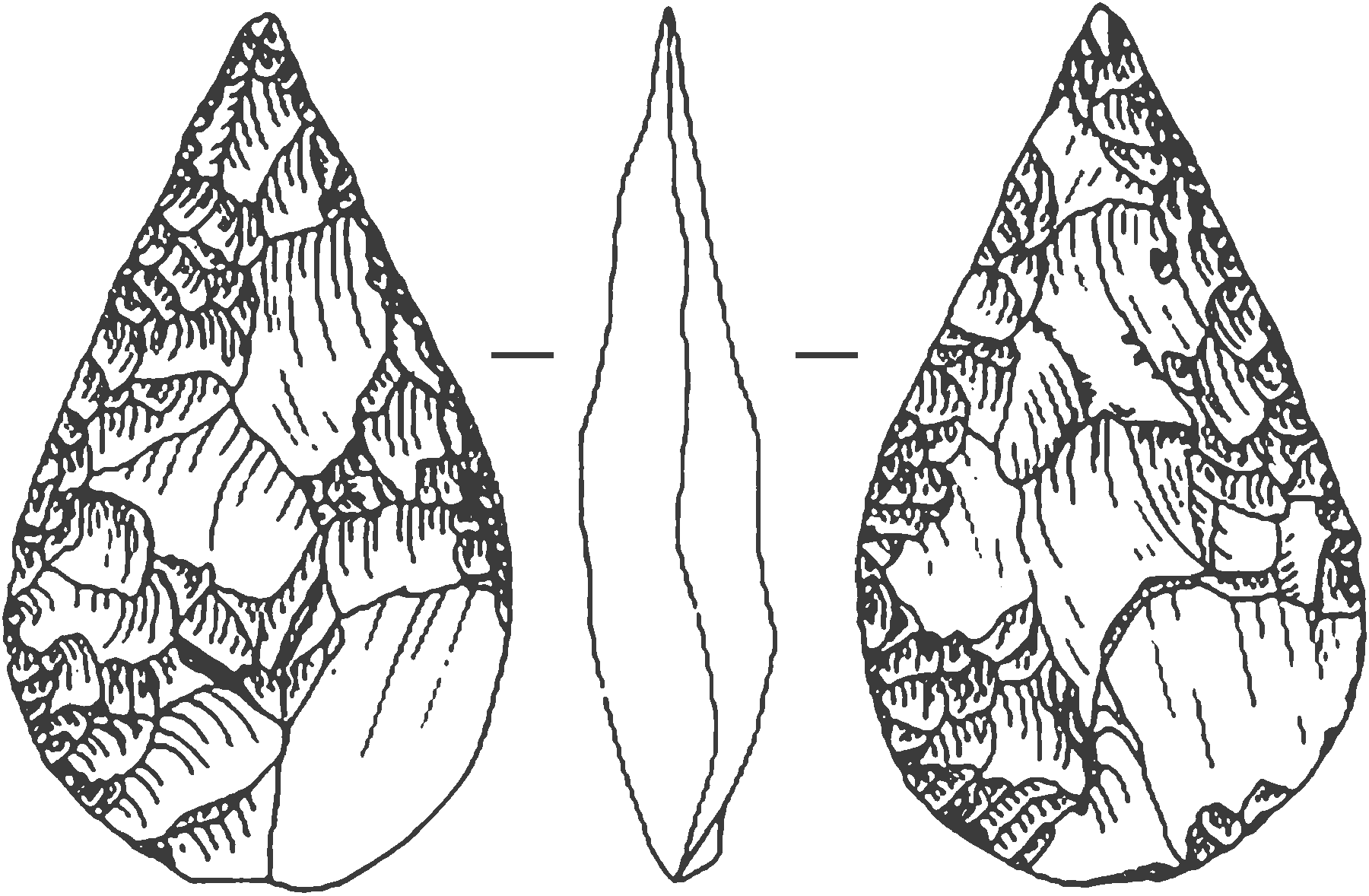

Late Acheulean handaxe from Kathu Pan, South Africa

According to Clark (1994), evidence for use of fire, thought postulated by 1 myr, is only made definitive by .5 myr, with the discovery of several sites, including burnt bone at Verteszoellos; charcoal, burnt bone, ash and burned stone at Zhoukoudian; and other materials at sites like Terra Amata and Gesher Benot Ya'aqov . Reddened patches from Koobi Fora dated to 1.6 myr likely represent repeatedly used hearths, according to thermal and paleomagnetic data (Wrangham et al., 1999). Brain and Sillen (1988) also report burnt bones from sediments containing hominin fossils from 1-1.5 myr. Refining the dates for the appearance of fire is important because cooking has both energetic importance in human evolutionary history as well as significant implications for social structure. According to Wrangham et al (1999), cooking food is responsible for the social system we know today as pair-bonding within a multi-male, multi-female group. Thus, it's clear that the advent of the use of fire could have had a significant effect on hominin social patterns and, in turn, diet.

And, although still in dispute, it's likely that hominins' skill in hunting greatly improved in this period. Acheulean tools have been found in association with butchered elephant and hippopotamus skeletons, for example, suggesting elephant hunting at the site of Torralba and Ambrona, although this is disputed (Clark, 1994). Speth (1989), for example, contends that early hominins ate less meat than we give them credit for, positing that meat's low energy value during times of stress made it an inefficient fallback food.

Raw material types used in Acheulean handaxe

Australopithecines most likely subsisted on a diet composed primarily of plant material, which would have largely been energy-poor resources, as evidenced by isotope data and the diets of modern subtropical foragers. More energy-rich foods like meat start showing up in the form of butchered bones during the Oldowan about 2.3 myr, which is followed by a reduction in hominin tooth size after 2 myr. Homo erectus, the makers of the Acheulean, exhibit an increase in body mass, reduction in tooth size and enamel thickness, and concomitant increase in brain size suggesting an increase of energy expenditure by a margin of 80-85% over australopithecines (Wrangham et al., 1999). This strongly suggests that early hominins made at least supplemented their diet with meat, although the manner of their acquisition remains very much in debate.

The Acheulean technocomplex, though expansive in both time and space, represents a dynamic period in human evolutionary history. In this time period, australopithecines went extinct, genus Homo flourished, hominins reached the edges of the world (but hadn't quite made it to the Americas), cognitive capacity increased, meat-eating and cooking behavior picked up, and the handaxe tradition traveled from East Africa to Europe and India. There remain important questions regarding the possible cognitive or cultural underpinnings to the morphology of Acheulean tools, or absence thereof, as well as questions of their distribution and use. Whether or not the Acheulean technologies were static, the time period in which they were made and used was assuredly eventful. As a result, the better we understand the Acheulean, the better resolution we'll have for understanding a critical period in our evolution.

The Middle Paleolithic (Middle Stone Age) marks the period of time subsequent to the Lower Paleolithic, characterized by the rise and decline of the

Neanderthals and their culture. The predominant industry of this era is termed the Mousterian, named for its type-site Le Moustier, a rock shelter in Dordogne, France (Chase and Dibble, 1987). Though first known from Western Europe, the geographical expanse of the Mousterian ranged from Europe through the Middle East and even into Northern Africa. The temporal range of Levantine sites extend back 215+/-30 ka, according to recent ESR and oxygen isotope dating methods (Porat et al., 2002). The makers of the tools from each region can be roughly divided into which species existed in those areas at the time -

Neanderthals in Europe, anatomically

modern humans in Northern Africa.

Neanderthals and

modern humans, however, became overlapping both geographically and temporally during the later Middle Paleolithic in the Levant, during which time the attribution of said tools becomes muddled (Shea, 2003; Tyron et al., 2006). This transition from

Neanderthal dominance to extinction and rise of

modern humans makes the Middle Paleolithic a critical time period in hominid evolution, in terms of both technological and cultural innovation.

The Mousterian is defined by the appearance of a method of stone-knapping or reduction known as the Levallois Technique, named after the type site in the Levallois-Perret suburb of Paris, France (Eren and Lycett, 2012). Traditionally, the Levallois Technique was dated to 300 kyr, helping to define the very beginning of the Middle Paleolithic. Closer analyses reveal that Levallois may have developed from Acheulean tools themselves. A longitudinal study of Kapthurin Formation of Kenya, for example, examined a sequence of Acheulean and Middle Stone Age hominin sites aged ~200-500 kyr and suggests that the Levallois developed directly from local Acheulean technologies in a mosaic fashion (Tyron et al., 2006). Levallois involves very basically the striking of flakes from a prepared core. A knapper would take this core and trim the edges by flaking off pieces around the outline of one's intended flake. After many uses, the core would acquire a distinctive tortoise-shell appearance (Whitaker 1994). This technique allows greater control over the size and shape of the flake products, but it also indicates a great leap from the cognitive requirements of previous Acheulean technologies.

Mousterian tools, including Levallois flakes, initially evaded easy classification and eventually came to be the topic of one of the classic archaeological debates of the 20th century - How should one classify Mousterian tools? The debate was argued by the American Louis Binford and the French Francois Bordes and became known as the Bordes-Binford debate. In it, Bordes claimed that the diversity of Mousterian tools across time and geography represented the various tribes that produced them. Binford, on the other hand, contended that variation reflected local raw material availability as well as the effects of resharpening and reduction, called the Frison Effect (Dibble, 1995). Recent work on stone tool reduction (see Dibble, 1995) and the enormous geographical and temporal spread of the Mousterian make Bordes' side rather unlikely, it's hardy to deny that Mousterian knapping techniques, especially the Levallois, express a landmark in our understanding of human cognitive evolution.

This landmark is the first fairly definitive evidence of planning and forethought in the archaeological record. Several other plausible and older examples have since been proposed; see for example Braun et al., (2008). Levallois assumes that the makers of the tools have a flake in mind when they go about creating and preparing the core. This idea has, of course, been challenged with the argument that raw material and technological constraints account for some to all of the variation seen in Levallois flakes. That is, size and shape of the flakes can be explained by physical parameters - not cognitive breakthroughs (Schlanger, 1996). Luckily in recent years it's become easier and more reliable to reconstruct cores from flint-knapping debitage. According to Schlanger (1996), reconstructing the knapping sequences of such a core revealed the 'structured and goal-oriented' flaking process of the Mousterian knapper (see also Eren and Lycett, 2012). Although there are still doubts as to the significance of Levallois, examples of cognitive increases become more common and more robust as the Mousterian developed.

A particular example of the evolution of Middle Paleolithic lithic culture comes in the form of the Aterian - a spear point technology derived from or a part of the Mousterian. The temporal genesis of Aterian tools remains unclear as research is just starting into the antiquity of this technology, but may be considered contemporaneous with Mousterian (Dibble et al., 2013). Aterian tools are differentiated from the rest of the Mousterian by the presence of a tang, which have been presumed to function as hafting stems for projectiles (Iovita, 2011). The status of Aterian tanged tools as true spear points, however, remains controversial and essential to conversation on the evolution of hunting behavior. Human agency in the deaths of large game for consumption can be observed very early in hominid history with trace evidence. At Gesher Benot Ya'akov, for example, there reports of in situ processing of fallow deer carcasses by 780 kyr using presumed cut-marks (Wilkins et al., 2012). Physical evidence of spears themselves begin a striking 300 kyr with a set of long, pointed shafts from Schoningen, Germany. Their status as functionally throwing spears, however, is contested, as the weight and diameter of these shafts significantly exceed those of ethnographic spear samples (Shea, 2006). Later in the Middle Paleolithic, Aterian tools start showing up across Northern Africa, providing even more physical evidence of spear-throwing behavior.

Traditionally thought of as spear points, researchers such as Iovita (2011) claim that the morphology of these artifacts lies outside the accepted parameters for projectiles. The criteria for classifying stone tip spear points includes factors like tip cross-sectional area, artifact symmetry, hafting, and presence of edge wear (Shea, 2006; Wilkins et al., 2012). Iovita (2011) argues that the tips of Aterian tools are highly variable, which would be unexpected if that were the active zone of the tool. Instead, this supports the idea that the active region of Aterian tools was located on the haft and that they function more as scrapers subjected to repeated resharpening events. Although this does not necessarily preclude function as a projectile weapon, Iovita's 2011 study suggests that additional evidence must be accumulated for the debate on early spear point technology and hunting.

Hunting behavior is important in human evolutionary history for myriad reasons, including as a signal for cognitive advancement - a concept essential to the primary question of the Middle Paleolithic. That is, who were the

Neanderthals? What were they both physically and mentally capable of, and how was this affected by the encroachment of anatomically

modern humans? Our concept of the

Neanderthal has changed considerably over the past century - from mindless brute to empathetic cousin and back to uncertainty. Originally, anthropologists conceived of the

Neanderthal as an ape devoid of culture, driven to extinction by cognitively superior

modern humans. Evidence of cultural artifacts in

Neanderthal sites, however, contests this hypothesis. One of the most poignant examples is the grave.

One of the greatest themes in the human psyche has always been death and dying - our collective obsession has influenced everything from the formation of the world's religions to Shakespeare's authorship of Romeo and Juliet. The discovery of

Neanderthal burials, however, suggests that this relationship with death might not have belonged to humans alone.

Of course, putative

Neanderthal burials can look much different than what we today would consider a proper burial. Belfer-Cohen and Hovers (1992) define the criteria of a Middle Paleolithic burial to be the presence of a closed structure (a dug gravesite), exceptional preservation, and the presence of decorations or goods. The site of La Chapelle-Aux-Saints represents one of the most well researched and substantial for its age

Neanderthal burials from the late Middle Paleolithic. At this site, a

Neanderthal skeleton was discovered inside a burial pit cut into the bedrock, with no carnivore modification to the bones (Rendu et al., 2014). This indicates a purposeful placement of the body into the grave. Other sites give examples of decorations, including that of flowers, of ochre and pigment, and of perforated shells - although not always in the certain context of graves (Zilhao, 2012). It's plain that

Neanderthal cultural habits were more complex than originally thought, although their relationship with human culture remains unclear.

As research continues and the world of the Middle Paleolithic comes into clearer focus, the line between

Neanderthals and early

modern humans blur - technologically, culturally and even genetically. What is known in certainty is that after around 35 kyr,

Neanderthals came to extinction and the Middle Paleolithic ended. In the next tens of thousands of years,

modern humans would colonize every habitable continent on Earth. Technological innovation would proceed at exponential rates and cultural complexity would become increasingly nuanced until we arrived at the conditions of present day.

Neanderthal tools, cultures and genetic lineages may have continued into their successors, anatomically

modern humans, but only as vestiges.

Belfer-Cohen A and E Hovers (1992) In the Eye of the Beholder: Mousterian and Natufian Burials in the Levant. Current Anthropology 33.4: 463-471.

Braun DR, Plummer T, Ditchfield P, Ferraro JV, Maina D, Bishop LC and R Potts (2008) Oldowan Behavior and Raw Material Transport: Perspectives from the Kanjera Formation. Journal of Archaeological Sciences 35: 2929-2946.

Chase PG and H Dibble (1987) Middle Paleolithic Symbolism: A review of current evidence and interpretations. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 6: 263-296.

Dibble H (1995) Middle Paleolithic Scraper Reduction: Background, clarification and review of evidence. Journal of Archaeological Theory 2.4: 299-368.

Dibble HL, Aldeias V, Jacobs Z, Olszewski DI, Rezek Z, Lin SC, Alvarez-Fernandez E, Barshay-Szmidt CC, Hallett-Desguez E, Reed D, Reed K, Richter D, Steele TE, Skinner A, Blackwell B, Doronicheva E and M El-Hajraoui (2013) On the Industrial Attributions of the Aterian and Mousterian of the Maghreb. Journal of Human Evolution: 1-17.

Eren MI and SJ Lycett (2012) Why Levallois? A morphometric comparison of experimental 'preferential' Levallois flakes versus debitage flakes. PLoS ONE 7.1.

Iovita R (2011) Shape Variation in Aterian Tanged Tools and the Origins of Projectile Technology: A morphometric perspective on stone tool function. PLoS ONE 6.12.

Porat N, Chazan M, Schwarcz H and LK Horwitz (2002) Timing of the Lower to Middle Paleolithic Boundary: New dates from the Levant. Journal of Human Evolution 43.1: 107-122.

Rendu W, Beavval C, Crevecoeur I, Bayle P, Balzeau A, Bismuth T, Bourgignon L, Delfour G, Favre JP, Lacrampe-Cuyaubere F, Tavormina C, Todisco D, Turq A and B Maureille (2014) Evidence Supporting Neanderthal burial at La Chapelle-Aux-Saints. PNAS: 1-6.

Shea JJ (2003) Neanderthals, Competition and the Origin of Modern Human Behavior in the Levant. Evolutionary Anthropology 12: 173-187.

Shea JJ (2006) The Origins of Lithic Projectile Point Technology: Evidence from Africa, the Levant and Europe. Journal of Archaeological Sciences: 1-24.

Skinner et al. (2007) New ESR Dates for a New Bone-Bearing Layer at Pradayrol, Lot, France. Abstracts of the Paleoanthropology Society 2007 meetings.Schlanger N (1996) Understanding Levallois: Lithic technology and cognitive archaeology. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 6.2: 231-254.

Tyron CA, McBrearty S and PJ Texier (2006) Levallois Lithic Technology from Kapthurin Formation, Kenya: Acheulean origin and Middle Stone Age Diversity. African Archaeology Review 22.4: 199-229.

Whitaker JC (1994) Flintknapping: Making and understanding stone tools. University of Texas Press 1st ed.

Wilkins J, Schoville B, Brown KS and M Chazan (2012) Evidence for Early Hafted Hunting Technology 338: 942-945.

Zilhao J (2012) Personal Ornaments and Symbolism among the Neanderthals. Developments in Quaternary Science 16: 35-4