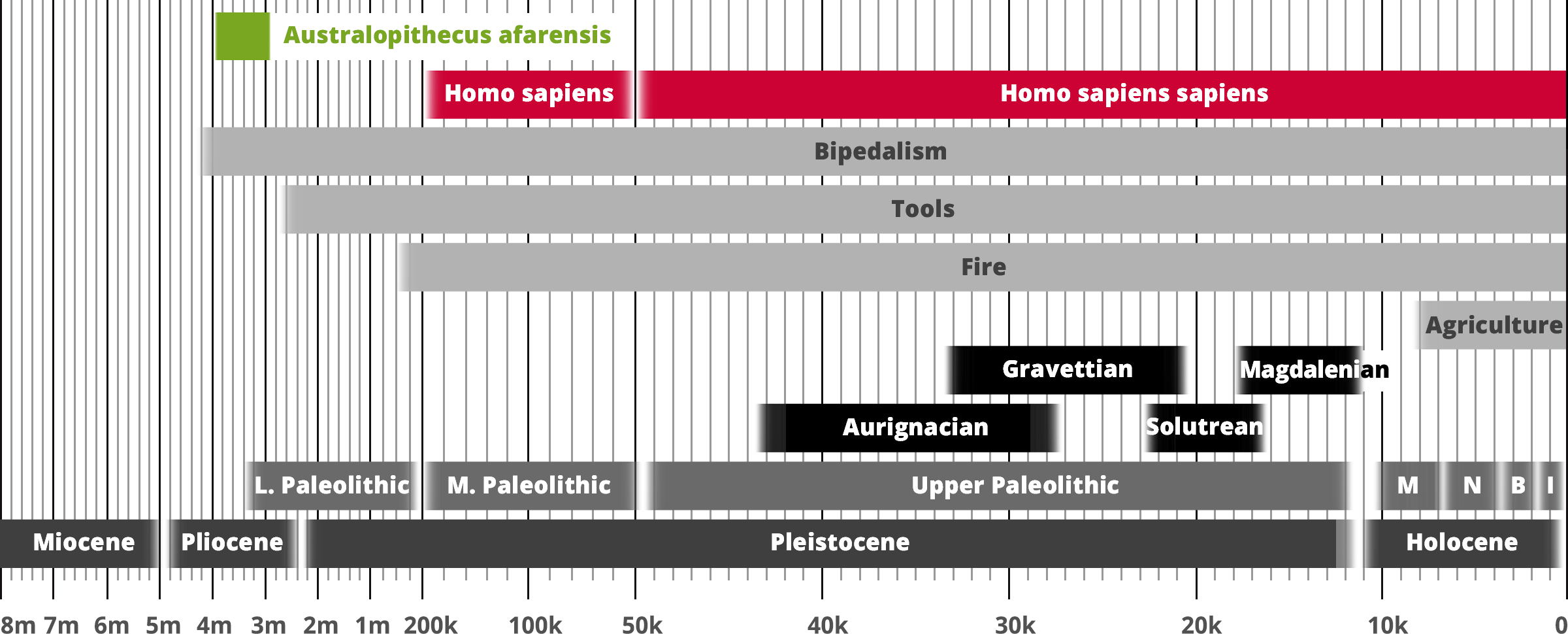

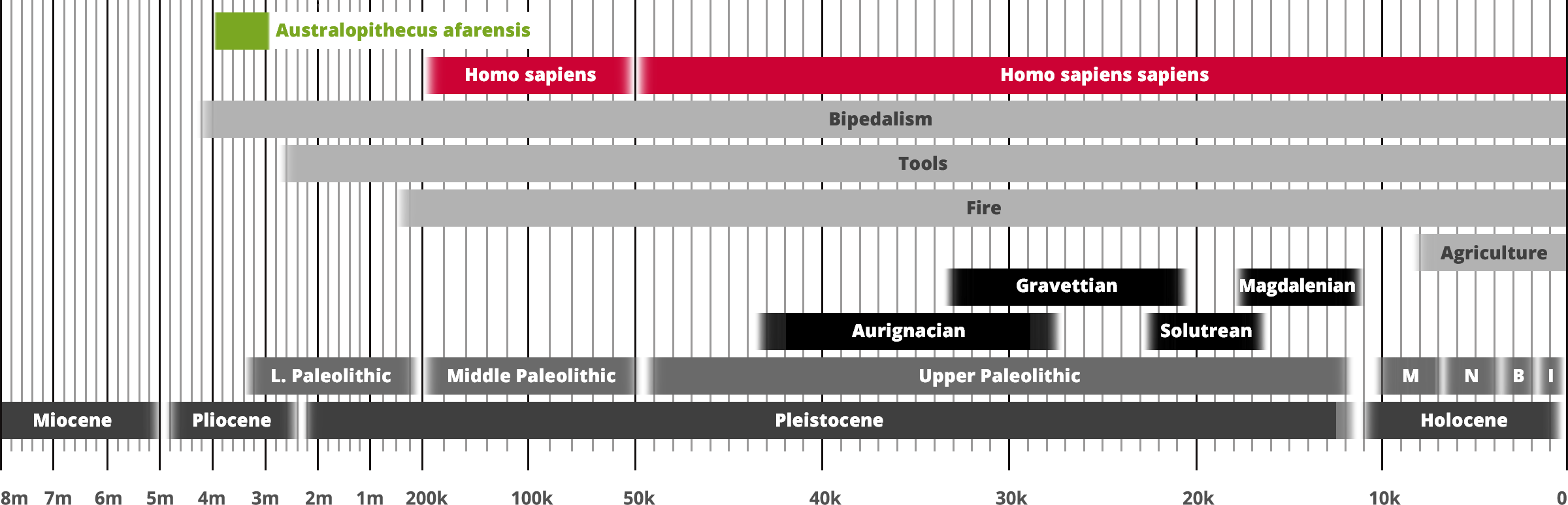

Australopithecus afarensis

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Period in human prehistory: M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic; B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research and scientific consensus

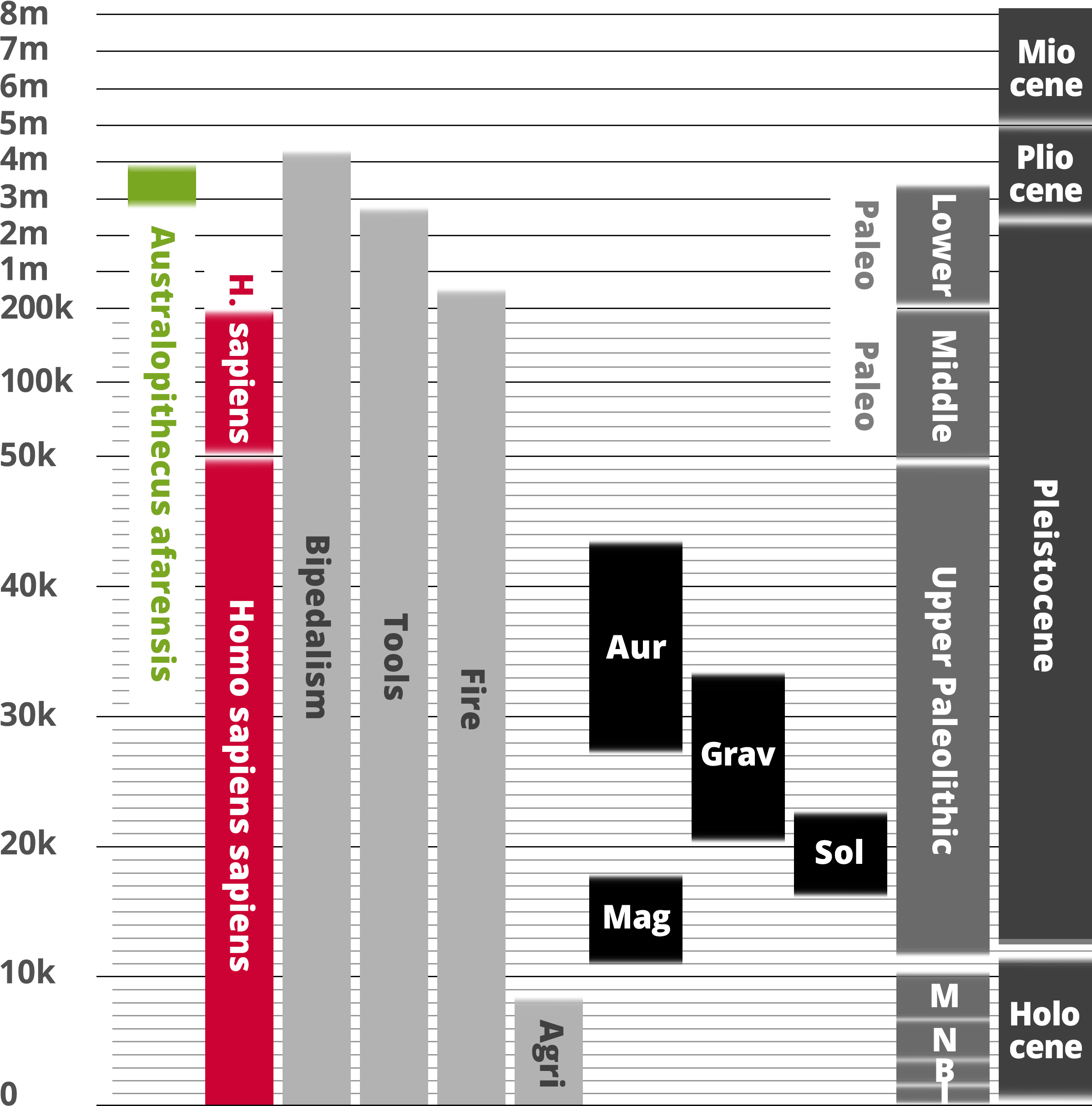

Australopithecus afarensis

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Aur = Aurignacian; Mag = Magdalenian;

Grav = Gravettian; Sol = Solutrean

Period in human prehistory:

M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic;

B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research

and scientific consensus

Australopithecus afarensis

| AUSTRALOPITHECUS AFARENSIS |

|

| Genus: |

Australopithecus |

| Species: |

Australopithecus afarensis |

| Other Names: |

• Lucy

• Dikika Baby |

| Time Period: |

3.9 to 2.9 million years ago |

| Characteristics: |

Bipedal, Scavenger, Tool User |

| Fossil Evidence: |

Partial Skeleton 'Lucy' Ethiopia, Africa |

Australopithecus afarensis, famously known as 'Lucy', is an extinct hominid that lived between 3.9 and 2.9 million years ago. Australopithecus afarensis was slenderly built, and closely related to the genus Homo, possibly as a direct ancestor or a close relative of an unknown ancestor. Lucy herself is 3.2 million years old, discovered by Donald Johanson and colleagues in the Afar Triangle region of Hadar in Ethiopia on November 24th 1974 [Johanson, D.C. 2009]. ‘Lucy’ was an almost complete skeleton. Australopithecus afarensis name Lucy was inspired by the Beatles song 'Lucy in the sky with diamonds'.

Other localities bearing Australopithecus afarensis remains include Omo, Maka, Fejej and Belohdelie in Ethiopia and Koobi Fora and Lothagam in Kenya.

Australopithecus afarensis has canines and molars relatively larger than in

modern humans, a relatively small brain size - 380 to 430 cm3 - and a face with forward projecting jaws. The anatomy of the hands, feet and shoulder joints suggest that the creatures were partly arboreal rather than exclusively bipedal, although in overall anatomy, the pelvis is far more human-like than ape-like. The change in the pelvis would infact have made child birth more difficult. Australopithecus afarensis would have had relatively short legs and long arms.

Australopithecus afarensis had replaced the opposable big toe with the arched foot, and was able to walk in almost the same way as modern humans, with a normal erect gait, as suggested by the Laetoli evidence. 'Lucy' represents a gradual bipedal transition between the chimp and the modern human. Australopithecus afarensis in Africa was probably becoming bipedal as a response to a changing climate, changing from a jungle to a savannah environment.

The Laetoli Footprints, the footprints of a family preserved in volcanic ash at a site in Tanzania just south of Olduvai gorge, were excavated and first studied by Louis and Mary Leaky in 1978.

Based on sexual dimorphism - the difference in body size between males and females - these creatures most likely lived in small family groups containing a single dominant and larger male and a number of smaller breeding females. 'Lucy' would have lived in a group culture, which would have required communication, perhaps verbal and certainly non-verbal, such as facial expressions.

In 2006 ‘Dikika baby’ was discovered by Dr. Zeresenay Alemseged in Ethiopia. The fossils are from a three year old infant that lived 3.3 million years ago.

Regarding the use of tools, evidence suggests the hominin species ate meat by carving animal carcasses with stone implements. Near the ‘Dikika baby’ site, animal bones were discovered showing fractures caused by stone tools. This finding pushes back the earliest known use of stone tools [rather than the making of stone tools] among hominins to about 3.4 million years ago [McPherron et al. 2010].

Stone tools may be older than humans

Reconstruction of a female Australopithecus

Laetoli fossil trackway, generally attributed to Australopithecus afarensis

In 2015 an online article on Nature by Ewen Callaway - Oldest stone tools raise questions about their creators - asks if the 3.3 million-year-old implements predate the first members of the Homo genus. Stone tools may be older than humans: complex tool-making in Africa might have begun before the genus Homo.

The Lomekwi stone tools - the oldest known - are now thought to disprove the fact that complex tool-making began with the genus Homo; a more ancient hominin ancestor may have been responsible.

Initially, the work of Louis and Mary Leaky in the 1950's and 1960's in the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania led to the term

Homo habilis - the handy man - marking the beginning of human stone-tool use, with the Oldowan tools dated at 2.6 million years ago, coinciding with (or triggered by) climate changes which transformed forest to savannah. A new environment called for new 'crafted' tools; striking a rock with another, to produce a sharp edge.

In 2010 fossil bones with marks at the Dikika archaeological site in Ethiopia from 3.4 million years ago, attributed to Australopithecus afarensis ('Lucy'), were thought to demonstrate early tool use, but this still remains controversial.

Now the latest research at the Lomekwi site (above) near Kenya's Lake Turkana has revealed tools that were made through a flaking process, from sediments dated to around 3.3 million years ago. These tools are also much larger - up to 15 kg - than the Oldowan artefacts, representing a distinct culture - the Lomekwian culture. Researchers do not know with certainty who made the tools, possibly

Kenyanthropus platyops or Australopithecus afarensis. The tools were made in a forest environment, not a drier savannah environment, which negates the climatic determinism referred to earlier.

Research is ongoing (Nature 520, 421 (23 April 2015) doi:10.1038/520421a), as is the debate.

Also in 2015 we saw the response to 'New Human Species Claim': the reaction to the recent discovery of a new human species, based on the fossil findings of the jaws and teeth, living alongside Lucy 3.4 million years ago.

In an article by Jeff St. Clair on wksu.org - Some scientists disagree with new fossil findings - we learn of the reaction to the recent discovery of a new human species, based on the jaws and teeth, living alongside Lucy 3.4 million years ago.

Cleveland Museum of Natural History curator Yohannes Haile-Selassie claims the jaw bones and teeth found recently in Ethiopia belong to a new species of early human that lived alongside a more commonly known ancestor.

Not so, says Kent State University professor Owen Lovejoy, who was part of the team in 1974 which discovered the famous specimen known as Lucy. He claims the teeth are not that different than Lucy's.

The debate comes down to how a new species is designated. A species is the fundamental taxonomic category used in biology. It is a very difficult judgement to make, especially in the fossil record where you are invariably looking at only a small portion of the animal, in this case, some teeth and jaws. The judgement is whether or not this constitutes a new lineage that lies outside the variation expected. The ranges of variation in scientific communities are, ironically, subjective.

In this case, Lovejoy argues that you are comparing things like molar and enamel thickness and size, and various characteristics of the dentition, and having to make the judgement as to whether these are significantly different than anything we have seen in Lucy's species to justify a new lineage.

Which he believes is not the case. Nor does Lucy co-discoverer Tim White at Berkeley, one of Haile-Selassie's mentors, and William Kimble, director of the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University.

Why? Lovejoy says it is down to habitat; part of his skepticism stems from the behavioral implications of adding a new species to the habitat occupied by Lucy. If it is a new lineage, then it means there were two contemporary lineages with character divergence, occupying different niches within the environment.

However, when we look at hominids in this particular time range, they all seem to share the same set of clear specializations, such as upright walking and small canines. The social implication is that if this is a separate species, they still had the same social structure as did Lucy's species.

The scientific debate continues. With the teeth, some scientists say they are within the variation seen within Lucy's species Australopithecus afarensis. Some do not.