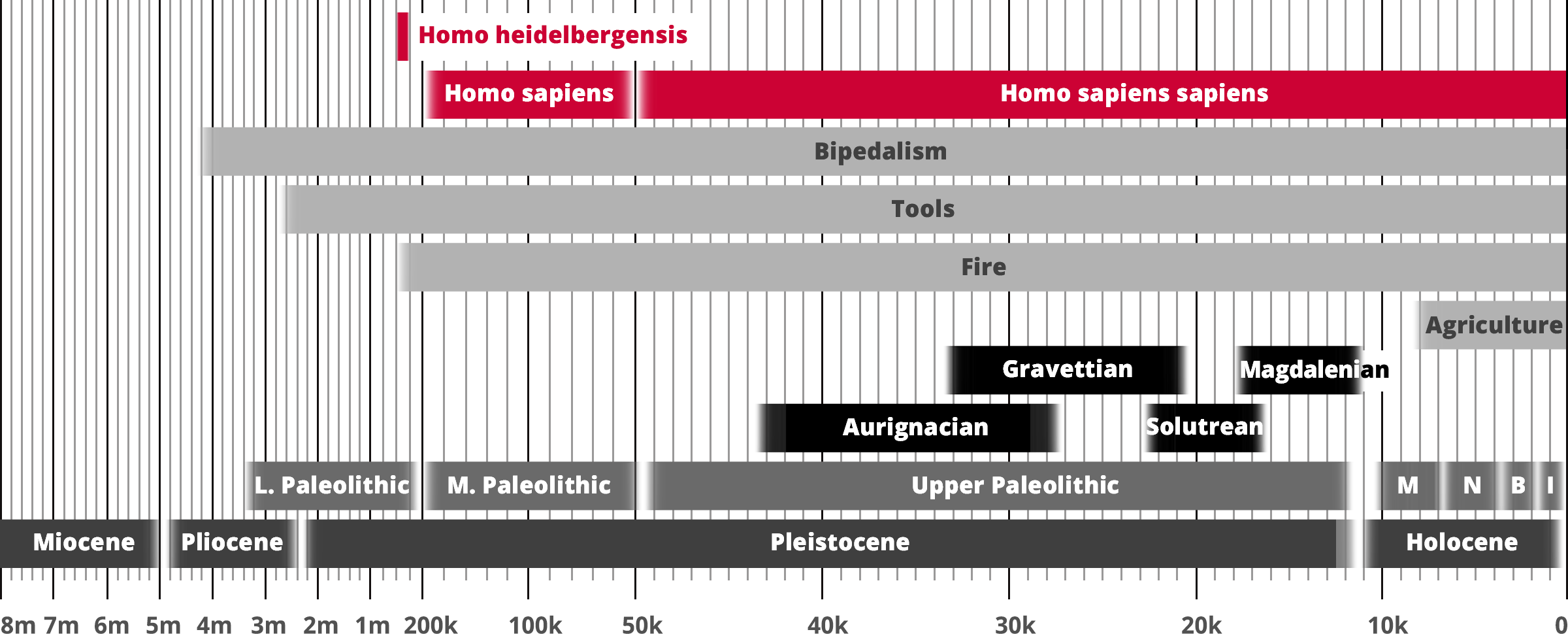

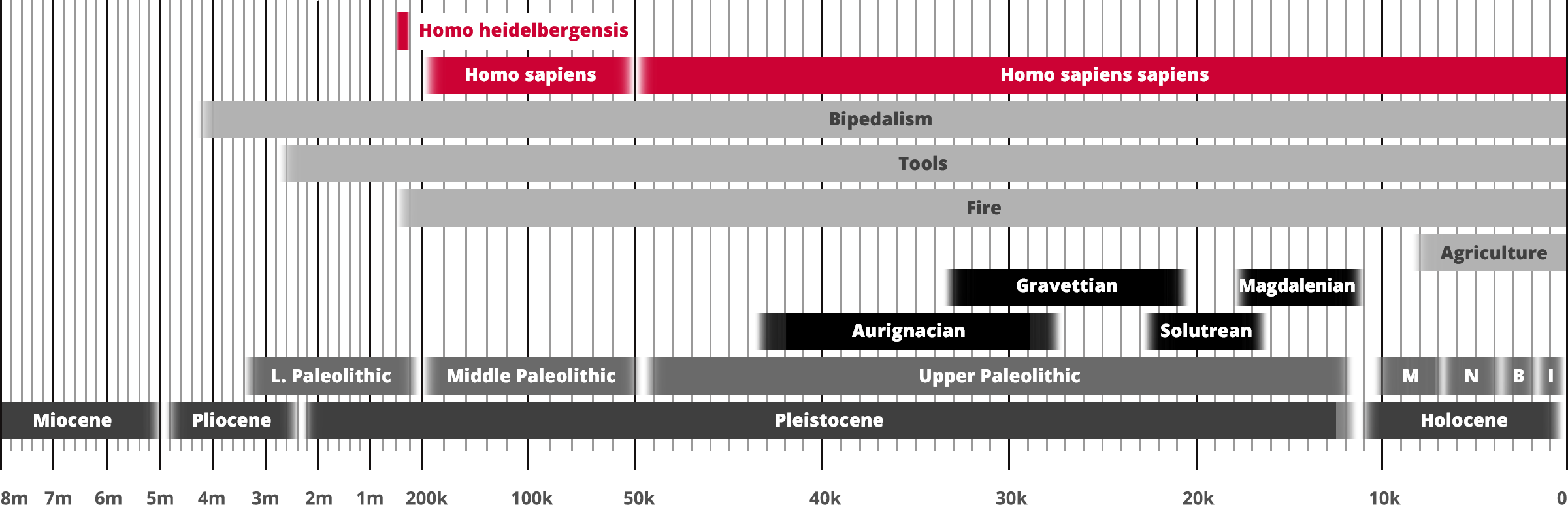

Homo heidelbergensis

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Period in human prehistory: M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic; B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research and scientific consensus

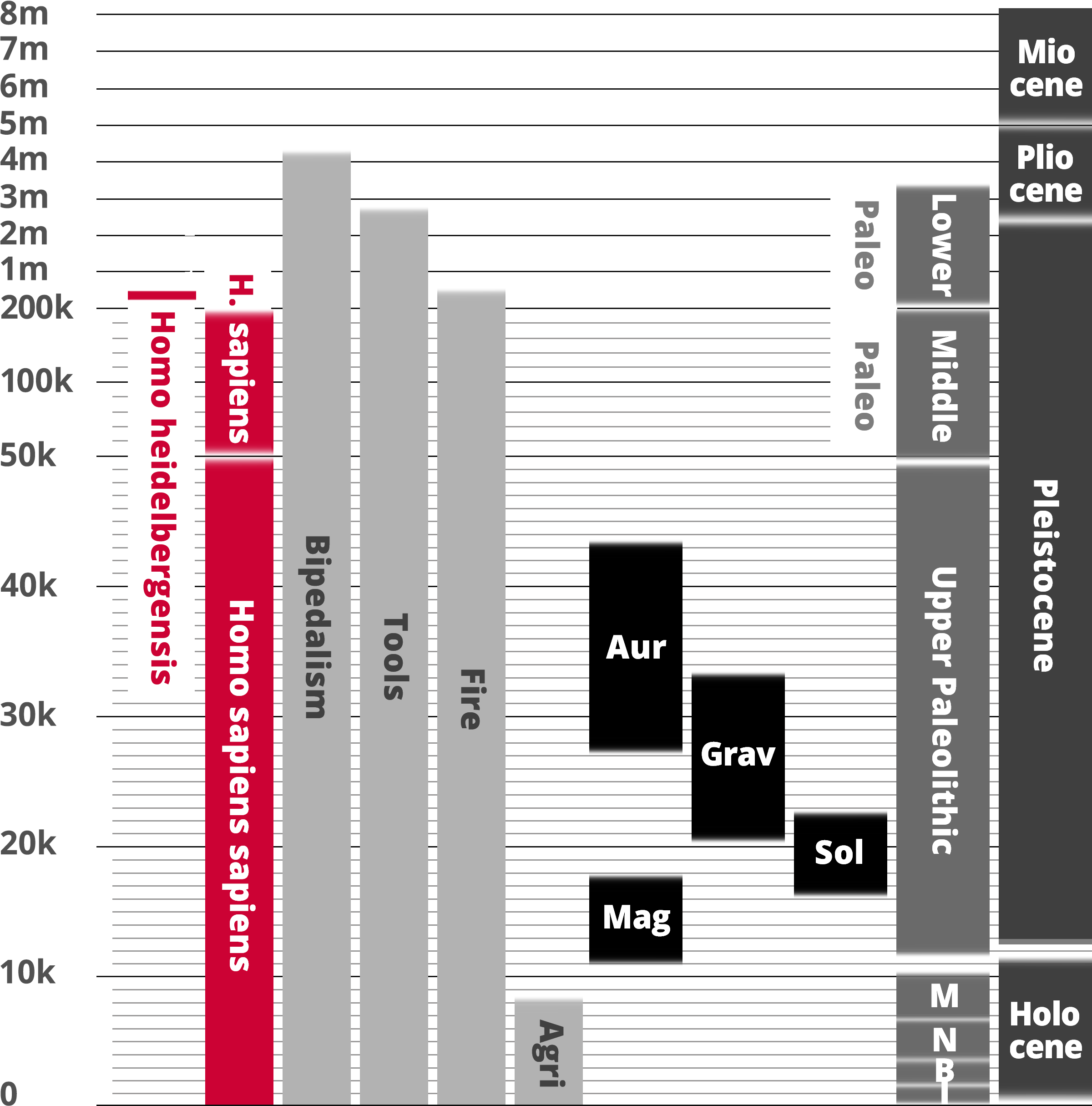

Homo heidelbergensis

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Aur = Aurignacian; Mag = Magdalenian;

Grav = Gravettian; Sol = Solutrean

Period in human prehistory:

M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic;

B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research

and scientific consensus

Homo heidelbergensis is an extinct species of the genus Homo which may be the direct ancestor of both

Homo neanderthalensis in Europe and

Homo sapien. The fossils have been dated to between 600,000 and 400,000 years ago. The tools used were very similar to those of the Acheulean tools used by

Homo erectus.

It has been argued that Homo heidelbergensis and the older

Homo antecessor are likely to be descended from

Homo ergaster from Africa, based on the close morphology. However, because Homo heidelbergensis had a larger average brain capacity than modern humans and used advanced tools, it has achieved its own species classification. Homo heidelbergensis was taller - averaging 7 ft - and more robust than

modern humans [Mounier 2009].

Regarding social behaviour, Homo heidelbergensis may have been the first species to bury their dead, based on 28 skeletons found at Atapuerca, Spain. Evidence suggests the development and use of a proto-language. The discovery of red ochre at Terra Amata indicates personal adornment. Dental analysis suggests they may have been right-handed. Homo heidelbergensis was a sophisticated hunter, suggested by wooden projectile spears found at Schoningen in Germany attributed to this species.

The first Homo heidelbergensis fossil discovery of this species was made in 1907 by Daniel Hartmann at Mauer in Germany. Other fossils have since been discovered in France, Greece, Italy, Spain and China. In 1994, a discovery was made in England at the Boxgrove Quarry site, known as 'Boxgrove Man'.

In terms of the evolutionary tree, with the spread of Homo heidelbergensis out of Africa and into Europe, the climate at this time would have caused a divergence:

Homo neanderthalensis diverged from Homo heidelbergensis probably some 300,000 years ago in Europe;

Homo sapien probably diverged between 200,000 and 100,000 years ago in Africa.

Middle Pleistocene communities in general seem to have eaten big game at a higher frequency than predecessors, with meat becoming an essential dietary component. In Europe, Homo heidelbergensis is known to have consumed the largest megafauna species present in the region, the straight-tusked elephant (which has been found at numerous sites with cut marks and/or stone tools indicating butchery) and rhinoceroses. At the Schöningen spear horizon in Germany, there is extensive evidence for the butchery of horses. At the Boxgrove site in England, there is evidence for the butchery of roe deer, horse and rhinoceros. The inhabitants of Terra Amata in France seem to have been mainly eating deer, but also elephants, boar, ibex, rhino and aurochs. African sites commonly yield bovine and horse bones. Though carcasses may have simply been scavenged, some Afro-European sites show specific targeting of a single species, which more likely indicates active hunting; for example: Olorgesailie, Kenya, which has yielded over 50 to 60 individual baboons; and Torralba and Ambrona in Spain which have an abundance of elephant bones (though also rhino and large hoofed mammals). The increase in meat subsistence could indicate the development of group hunting strategies in the Middle Pleistocene. For instance, at Torralba and Ambrona, the animals may have been run into swamplands before being killed, entailing encircling and driving by a large group of hunters in a coordinated and organised attack. Exploitation of aquatic environments is generally quite lacking, despite some sites being in close proximity to the ocean, lakes or rivers.

Plants were probably also frequently consumed, including seasonally available ones, but the extent of their exploitation is unclear as they do not fossilise as well as animal bones. At the Schöningen site in Germany, it is estimated that over 200 plant species in the vicinity were either edible raw or when cooked, though relatively few have actually been found at the site itself.

| HOMO HEIDELBERGENSIS |

|

| Genus: |

Homo |

| Species: |

Homo heidelbergensis |

| Other Names: |

• Heidelberg Man

• Boxgrove Man |

| Time Period: |

600,000 to 400,000 years ago |

| Characteristics: |

Tool Maker, Large Brain,Tall, Robust |

| Fossil Evidence: |

Homo heidelbergensis Cranium,

Sima de los Huesos, Atapuerca (Spain) |

Upper Palaeolithic modern humans are well known for having etched engravings seemingly with symbolic value. As of 2018, only 27 Middle and Lower Palaeolithic objects have been postulated to have symbolic etching, out of which some have been refuted as having been caused by natural or otherwise non-symbolic phenomena (such as the fossilisation or excavation processes). The Lower Palaeolithic ones are: a 400,000 to 350,000 years old bone from Bilzingsleben, Germany; three 380,000-year-old pebbles from Terra Amata; a 250,000-year-old pebble from Markkleeberg, Germany; 18 roughly 200,000-year-old pebbles from Lazaret (near Terra Amata); a roughly 200,000-year-old lithic from Grotte de l'Observatoire, Monaco and a 200- to 130-thousand-year-old pebble from Baume Bonne, France.

In the mid-19th century, French archaeologist Jacques Boucher de Perthes began excavation at St. Acheul, Amiens, France, (the area where the Acheulian was defined), and, in addition to hand axes, reported perforated sponge fossils (Porosphaera globularis) which he considered to have been decorative beads. This claim was completely ignored. In 1894, English archaeologist Worthington George Smith discovered 200 similar perforated fossils in Bedfordshire, England, and also speculated that their function was beads, though he made no reference to Boucher de Perthes' find, possibly because he was unaware of it. In 2005, Robert Bednarik reexamined the material, and concluded that - because all the Bedfordshire P. globularis fossils are sub-spherical and range 10–18 mm (0.39–0.71 in) in diameter, despite this species having a highly variable shape - they were deliberately chosen. They appear to have been bored through completely or almost completely by some parasitic creature (i. e., through natural processes), and were then percussed on what would have been the more closed-off end to fully open the hole. He also found wear facets which he speculated were begotten from clacking against other beads when they were strung together and worn as a necklace. In 2009, Solange Rigaud, Francisco d'Errico and colleagues noticed that the modified areas are lighter in colour than the unmodifed, suggesting they were inflicted much more recently such as during excavation. They were also unconvinced that the fossils could be confidently associated with the Acheulian artefacts from the sites, and suggested that—as an alternative to archaic human activity—apparent size-selection could have been caused by either natural geological processes or 19th-century collectors favouring this specific form.

Early modern humans and late Neanderthals (the latter especially after 60,000 years ago) made wide use of red ochre for presumably symbolic purposes as it produces a blood-like colour, though ochre can also have a functional medicinal application. Beyond these two species, ochre usage is recorded at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, where two red ochre lumps have been found; Ambrona where an ochre slab was trimmed down into a specific shape; and Terra Amata where 75 ochre pieces were heated to achieve a wide colour range from yellow to red-brown to red. These may exemplify early and isolated instances of colour preference and colour categorisation, and such practices may not have been normalised yet.

In 2006, Eudald Carbonell and Marina Mosquera suggested the Sima de los Huesos (SH) hominins were buried by people rather than being the victims of some catastrophic event such as a cave-in, because young children and infants are absent which would be unexpected if this were a single and complete family unit. The SH humans are conspicuously associated with only a single stone tool, a carefully crafted hand axe made of high-quality quartzite (rarely used in the region), and so Carbonell and Mosquera postulated this was purposefully and symbolically placed with the bodies as some kind of grave good. Supposed evidence of symbolic graves would not surface for another 300,000 years.

The Lower Palaeolithic comprises the Oldowan which was replaced by the Acheulian, which is characterised by the production of mostly symmetrical hand axes. The Acheulian has a timespan of about a million years, and such technological stagnation has typically been ascribed to comparatively limited cognitive abilities which significantly reduced innovative capacity, such as a deficit in cognitive fluidity, working memory, or a social system compatible with apprenticeship. Nonetheless, the Acheulian does seem to subtly change over time, and is typically split up into Early Acheulian and Late Acheulian, the latter becoming especially popular after 600 to 500 thousand years ago. Late Acheulian technology never crossed over east of the Movius Line into East Asia, which is generally believed to be due to either some major deficit in cultural transmission (namely smaller population size in the East) or simply preservation bias as far fewer stone tool assemblages are found east of the line.

The transition is indicated by the production of smaller, thinner, and more symmetrical hand axes (though thicker, less refined ones were still produced). At the 500,000-year-old Boxgrove site in England - an exceptionally well-preserved site with abundance of tool remains - thinning may have been produced by striking the hand axe near-perpendicularly with a soft hammer, possible with the invention of prepared platforms for tool making. The Boxgrove knappers also left behind large lithic flakes leftover from making hand axes, possibly with the intention of recycling them into other tools later. Late Acheulian sites elsewhere pre-prepared lithic cores in a variety of ways before shaping them into tools, making prepared platforms unnecessary.

Knappers would have had to have produced some item indirectly related to creating the desired product, which could represent a major cognitive development. Experiments with modern humans have shown that platform preparation cannot be learned through purely observational learning, unlike earlier techniques, and could be indicative of well developed teaching methods as well as self-regulated learning. At Boxgrove, the knappers used not only stone but also bone and antler to make hammers, and the use of such a wide range of raw materials could speak to advanced planning capabilities as stoneworking requires a much different skillset to work and gather materials for than boneworking.

Despite apparent pushes into colder climates, evidence of fire is scarce in the archaeological record until 400 to 300 thousand years ago. Though it is possible fire remnants simply degraded, long and overall undisturbed occupation sequences such as at Arago or Gran Dolina conspicuously lack convincing evidence of fire usage. This pattern could possibly indicate the invention of ignition technology or improved fire maintenance techniques at this time, and that fire was not an integral part of people's lives before then in Europe. In Africa, on the other hand, humans may have been able to frequently scavenge fire as early as 1.6 million years ago from natural wildfires, which occur much more often in Africa, thus possibly regularly using fire. The oldest established continuous fire site beyond Africa is the 780,000-year-old Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel.

In Europe, evidence of constructed dwelling structures - classified as firm surface huts with solid foundations built in areas mostly sheltered from the weather - has been recorded since the Cromerian Interglacial, the earliest example a 700,000-year-old stone foundation from Přezletice, Czech Republic. This dwelling probably featured a vaulted roof made of thick branches or thin poles, supported by a foundation of big rocks and earth. Other such dwellings have been postulated to have existed during or following the Holstein Interglacial (which began 424,000 years ago) in Bilzingsleben, Germany; Terra Amata, France; and Fermanville and Saint-Germain-des-Vaux in Normandy. These were probably occupied during the winter, and, averaging only 3.5 m × 3 m in area, they were probably only used for sleeping in, while other activities (including firekeeping) seem to have been done outside. Less-permanent tent technology may have been present in Europe in the Lower Paleolithic.

Excavation of the Schöningen spears: the appearance of repeated fire usage - earliest in Europe from Beeches Pit, England, and Schöningen, Germany - roughly coincides with hafting technology (attaching stone points to spears) best exemplified by the Schöningen spears. These nine wooden spears and spear fragments - in addition to a lance, and a double-pointed stick - date to 300,000 years ago and were preserved along a lakeside. The spears vary from 2.9–4.7 cm in diameter, and may have been 210–240 cm long, overall similar to present day competitive javelins. The spears were made of soft spruce wood, except for spear 4 which was (also soft) pine wood.[3] This contrasts with the Clacton spearhead from Clacton-on-Sea, England, perhaps roughly 100,000 years older, which was made of hard yew wood. The Schöningen spears may have had a range of up to 35 m though would have been more effective short range within about 5 m, making them effective distance weapons either against prey or predators. Besides these two localities, the only other site which provides solid evidence of European spear technology is the 120,000-year-old Lehringen site, district of Verden, in Lower Saxony, Germany, where a 238 cm yew spear was apparently lodged in an elephant. In Africa, 500,000-year-old points from Kathu Pan 1, South Africa, may have been hafted onto spears. Judging by indirect evidence, a horse scapula from the 500,000-year-old Boxgrove shows a puncture wound consistent with a spear wound. Evidence of hafting (in both Europe and Africa) becomes much more common after 300,000 years.

The SH humans (Sima de los Huesos) had a modern humanlike hyoid bone (which supports the tongue), and middle ear bones capable of finely distinguishing frequencies within the range of normal human speech. Judging by dental striations, they seem to have been predominantly right-handed, and handedness is related to the lateralisation of brain function, typically associated with language processing in modern humans. So, it is postulated that this population was speaking with some early form of language. Nonetheless, these traits do not absolutely prove the existence of language and humanlike speech, and its presence so early in time despite such anatomical arguments has been primarily opposed by cognitive scientist Philip Lieberman.