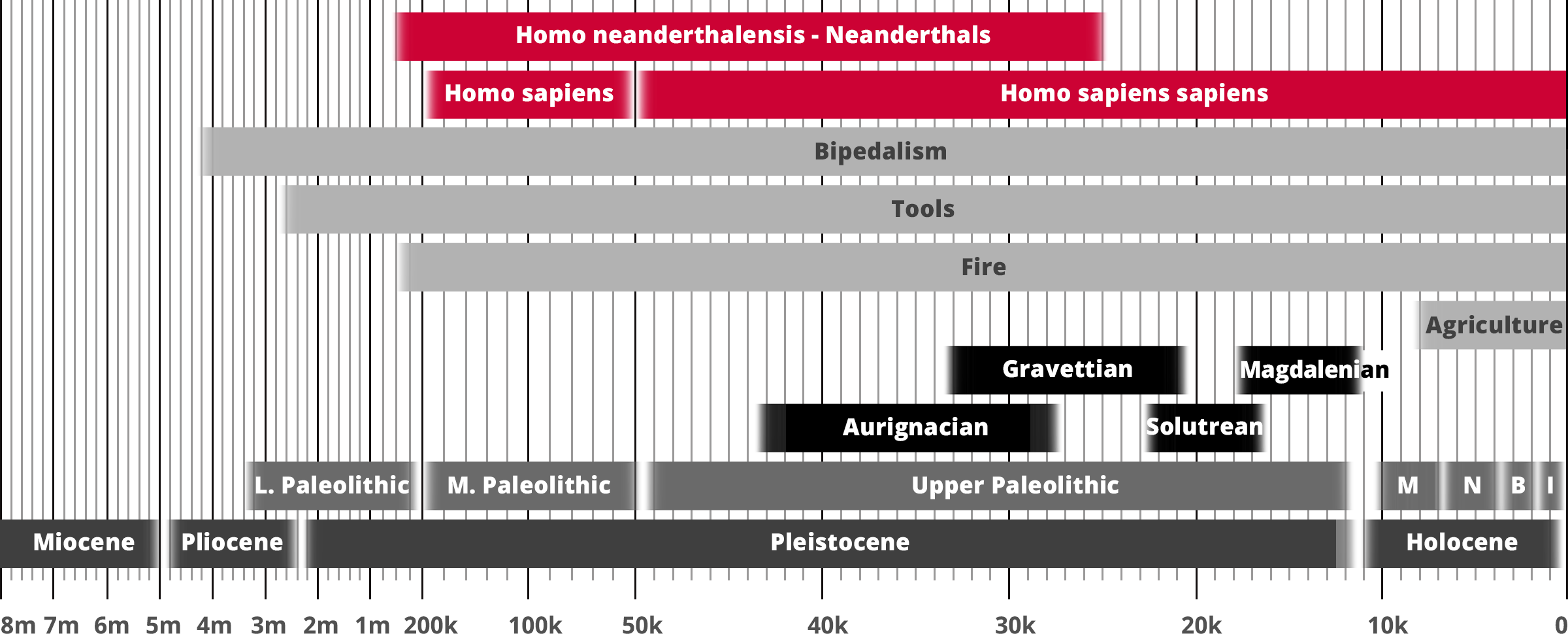

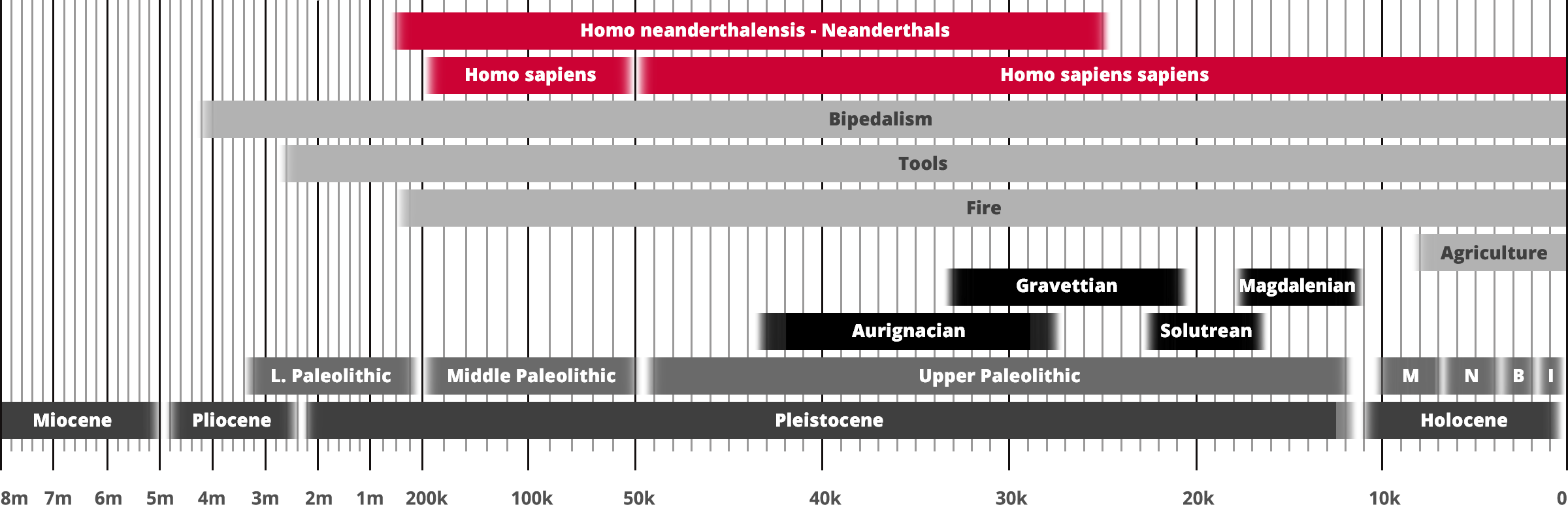

Homo neanderthalensis - Neanderthals

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Period in human prehistory: M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic; B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research and scientific consensus

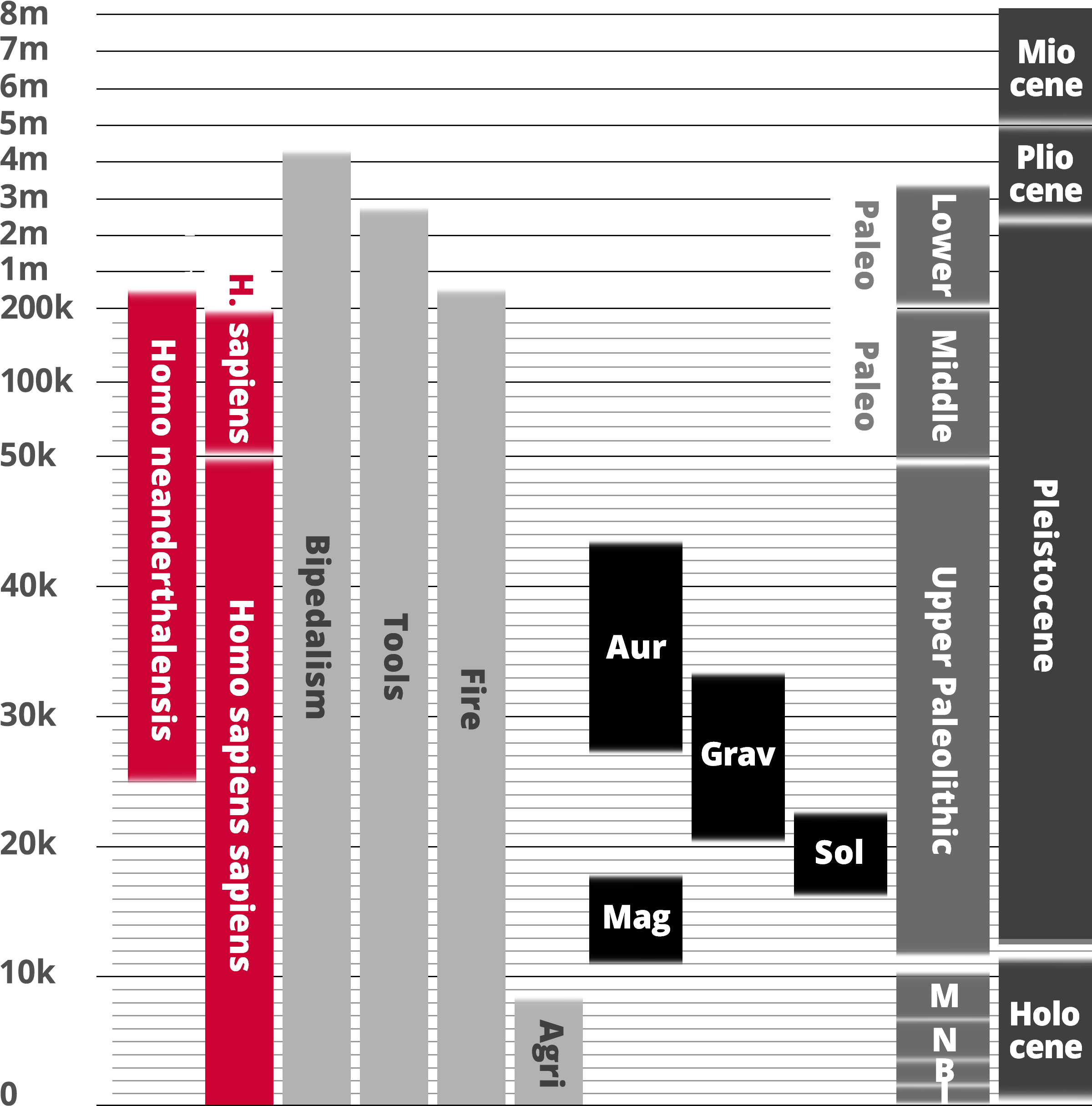

Homo neanderthalensis - Neanderthals

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Aur = Aurignacian; Mag = Magdalenian;

Grav = Gravettian; Sol = Solutrean

Period in human prehistory:

M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic;

B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research

and scientific consensus

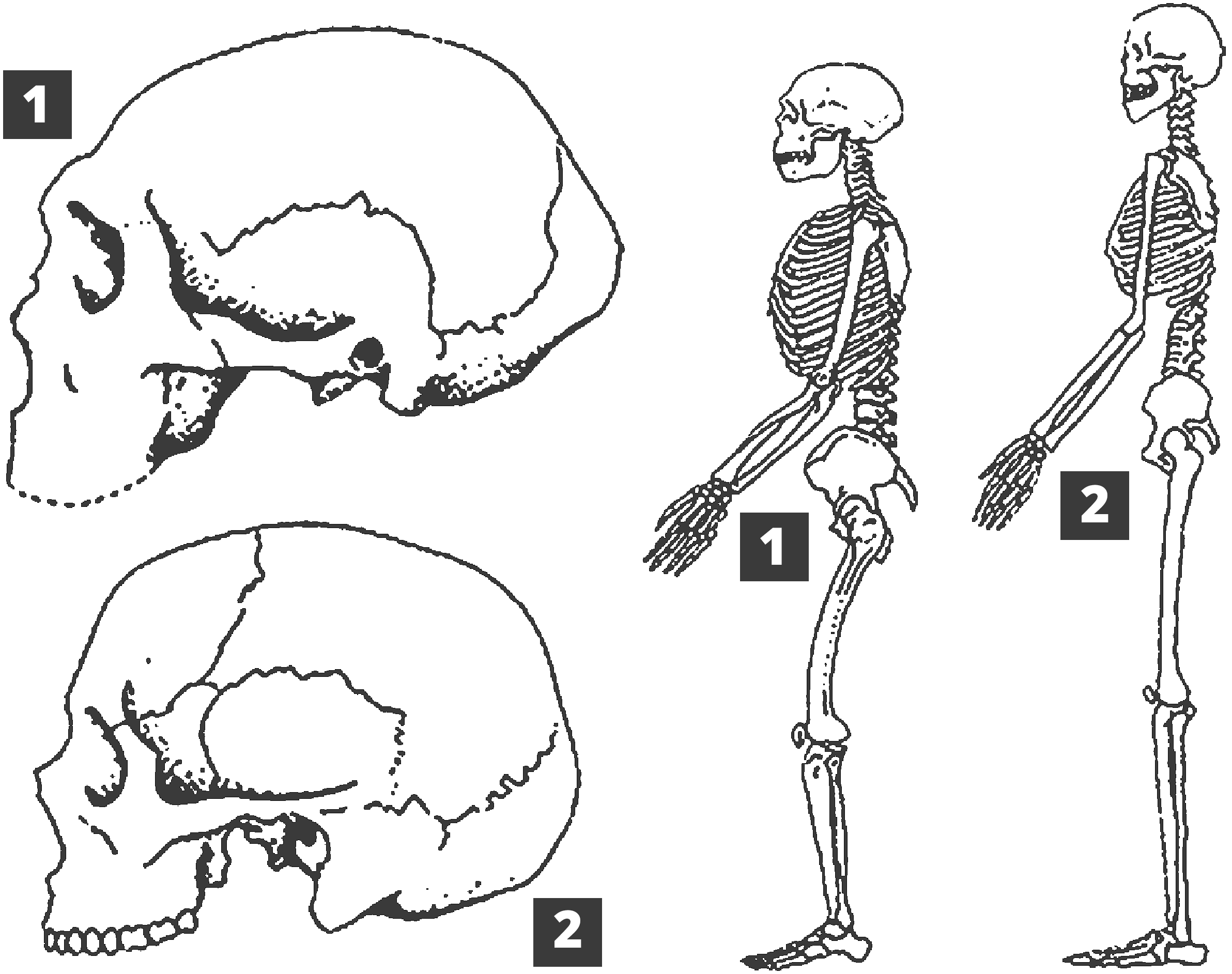

Neanderthal cranial capacity is thought to have been as large as that of

modern humans. They were much stronger than modern humans, with an average male height of 5.5 feet. Neanderthals evolved from early Homo along a path either identical or very similar to modern man. From mtDNA analysis estimates, the two species shared a common ancestor about 500,000 years ago before diverging. The last common ancestor between anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals appears to be

Homo heidelbergensis (or possibly

Homo rhodesiensis). Approximately 600,000 years ago, Homo heidelbergensis migrated out of Africa into Europe, to become the Neanderthal, whilst back in Africa, Homo heidelbergensis became

Homo sapien.

| HOMO NEANDERTHALENSIS |

|

| Genus: |

Homo |

| Species: |

Homo neanderthalensis |

| Other Names: |

Neanderthals |

| Time Period: |

600,000 to 25,000 years ago |

| Characteristics: |

Neanderthal skulls, first discovered, Engis Caves, Belgium, Europe |

| Fossil Evidence: |

Partial Skeletons, Flores, Indonesia |

Genetic evidence may suggest that Homo neanderthalensis contributed DNA to anatomically modern humans probably through interbreeding, possibly between 80,000 and 50,000 years ago, although this is now disputed [Richard E. Green et al [2010]. Szante Pääbo’s DNA sequencing from a Neanderthal bone fragment showed that Neanderthals and modern humans share about 99.5% of their DNA. Some now believe the source population of non-African modern humans was already more closely related to Neanderthals than other Africans were, due to ancient genetic divisions within Africa.

Cultural assemblages associated with the Neanderthals in Europe include the Mousterian stone tool culture of 300,000 years ago, the Châtelperronian, Aurignacian and Gravettian cultures.

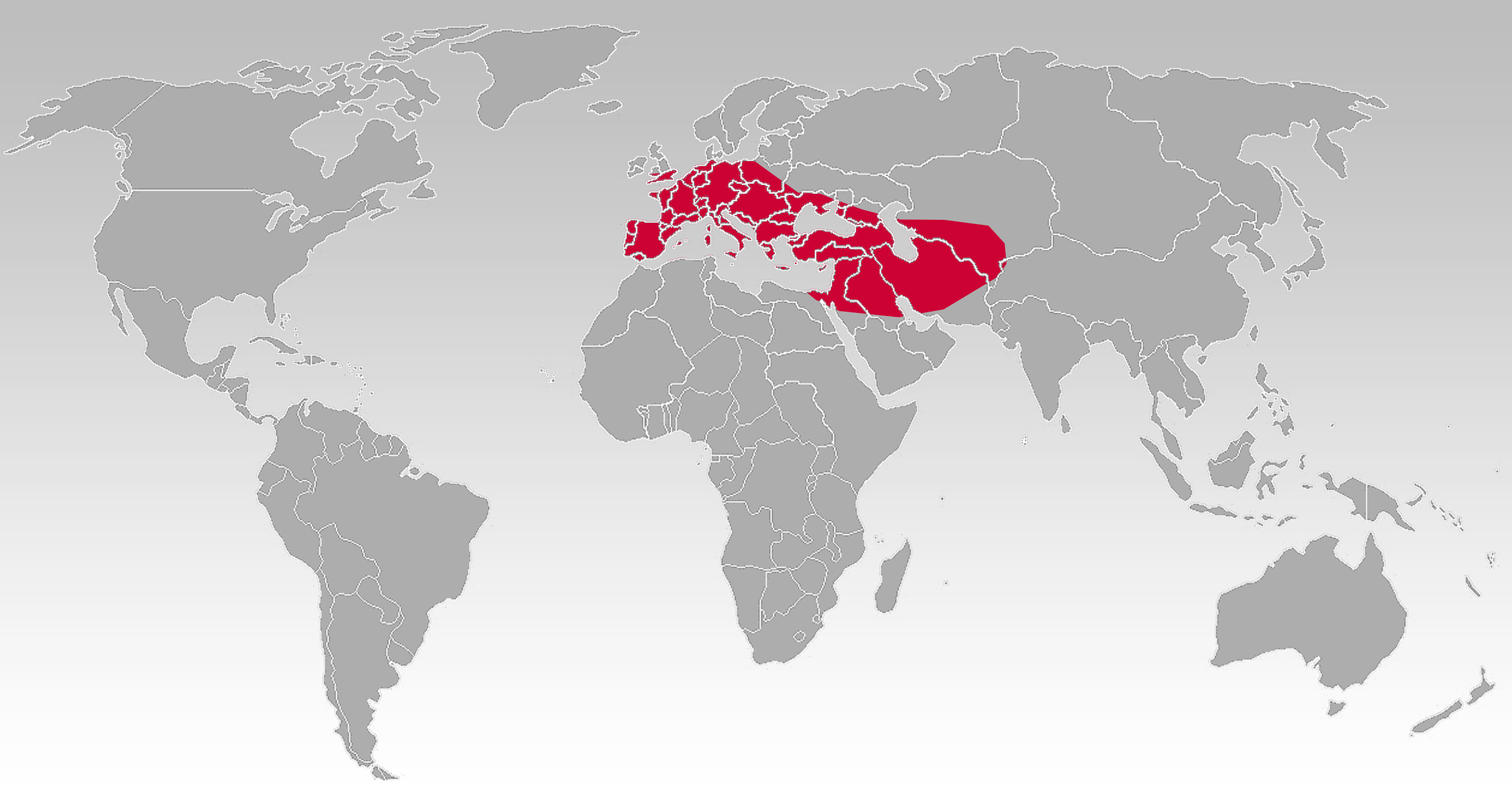

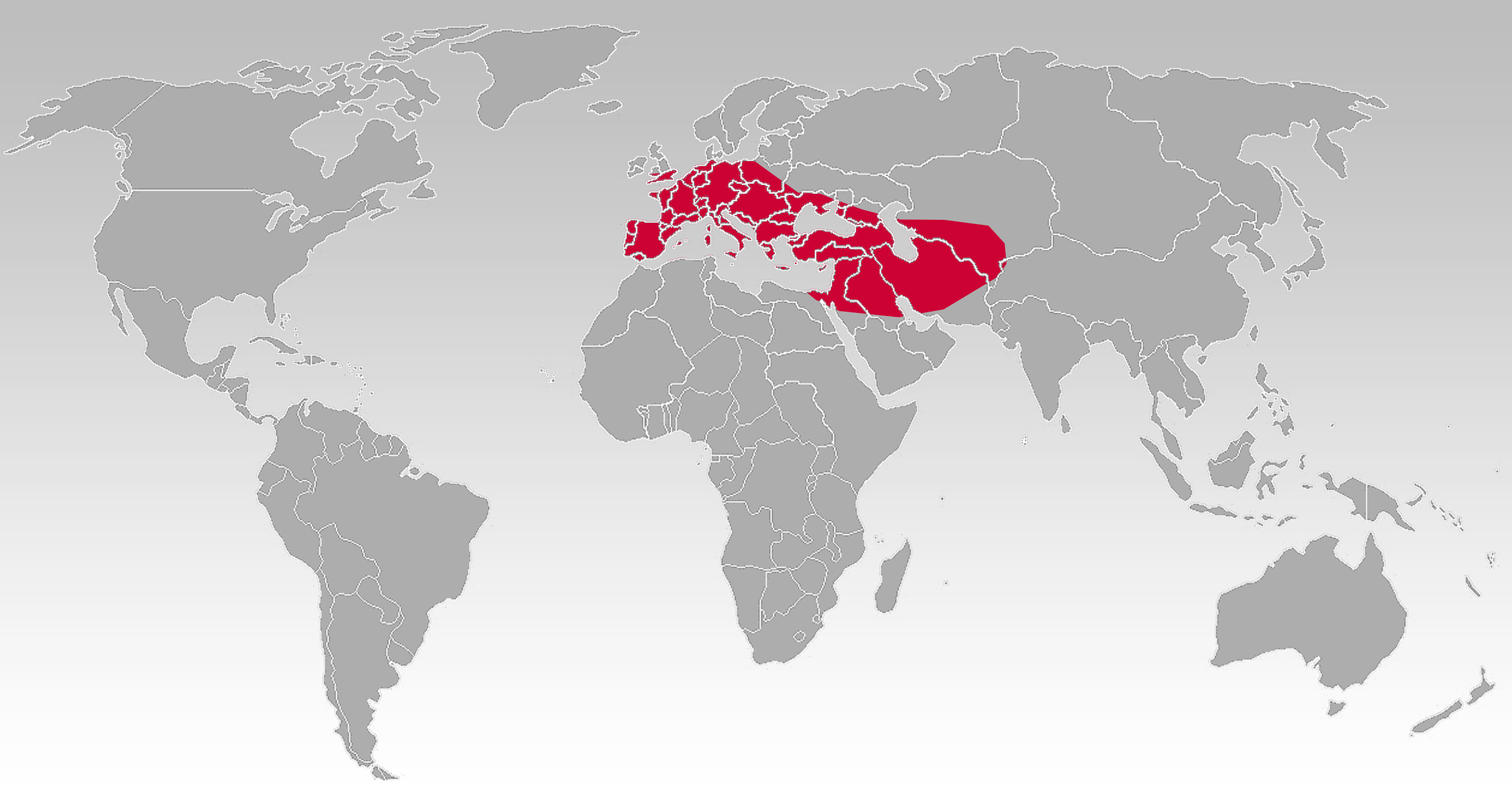

To date, over 400 Neanderthals have been found, including most of Europe south of the line of glaciation [the 50th parallel north], the Balkans, Ukraine, western Russia and Siberia, and the Levant.

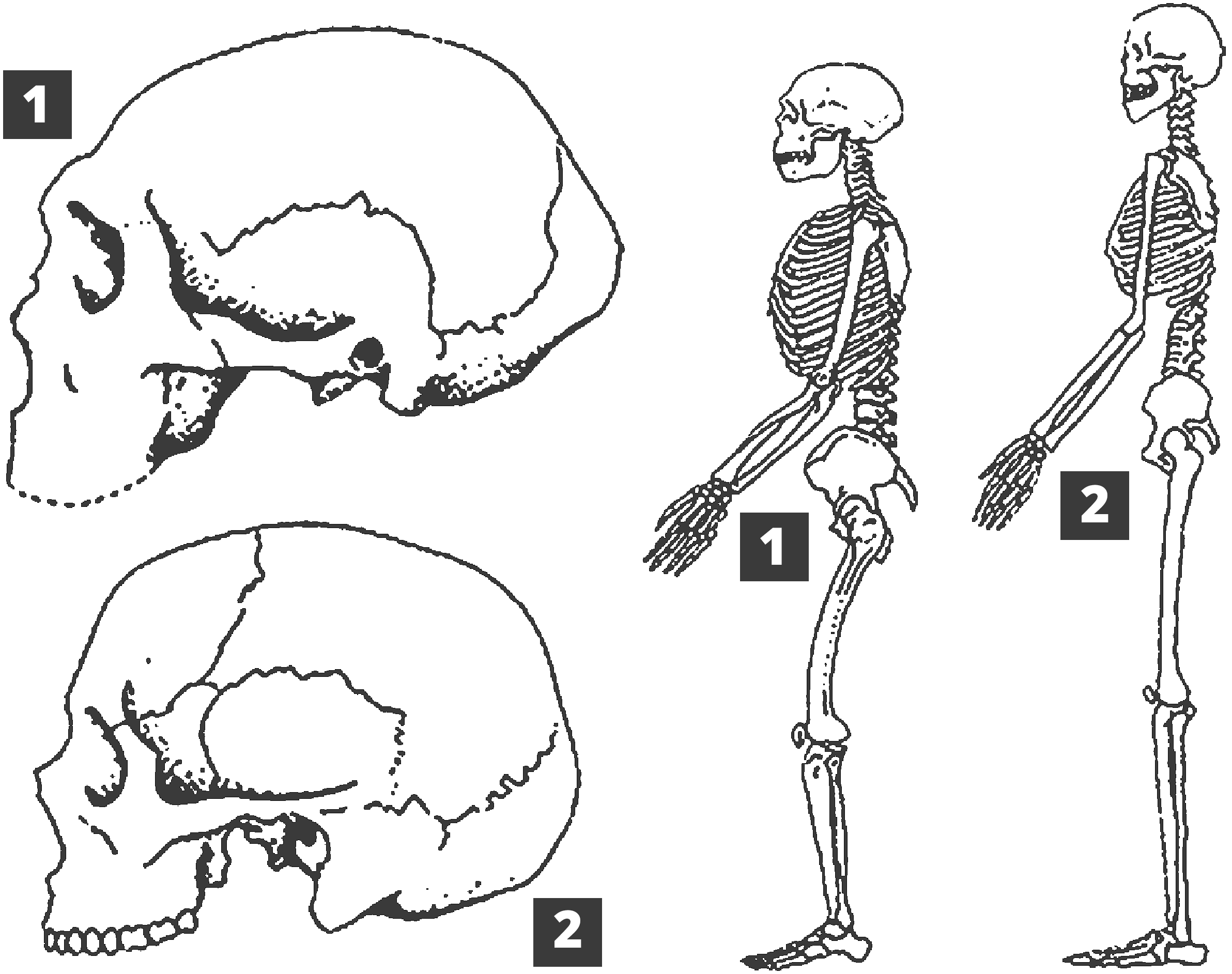

1) Homo neanderthalensis

2) Homo sapiens

Neanderthals were better adapted biologically to cold weather than modern humans. When further climate change caused warmer temperatures, the Neanderthal range retreated to the north along with the cold-adapted species of mammals.

Neanderthals were hunters. Bone fossils such as the [oval-shaped] humorous, reveal the use of spears in stabbing [rather than throwing] in close-quarter hunting of woolly mammoths, horse, and deer, for example. Garments of animal hides were used. Teeth show signs of heavy wear, suggesting they were used as tools to make garments. Elements of culture are demonstrated by excavated relics such as the painted shells discovered in Spain, used as pendants up to 37,000 years ago. They had a form of language [demonstrated by the presence of the hyoid bone] and lived in complex social groups. The Molodova archaeological site in eastern Ukraine suggests the use of dwellings assembled from mammoth bones with hearths. They were hunters [alpha predators] but with a mixed diet.

Why did the Neanderthals become extinct? Currently the most likely scenario is that Neanderthals were a separate species from modern humans, and became extinct (due to climate change and/or interaction with humans) and were replaced by 'competitive' modern humans moving into their habitat beginning around 80,000 years ago. In other words, Homo neanderthalensis was out-competed and marginalized [largely by a warmer and fluctuating climate] to extinction by the more 'adaptable' Aurignacians. The rapid fluctuations of weather caused ecological changes to which the Neanderthals could not adapt; familiar plants and animals would be replaced by completely different ones within a lifetime. Neanderthals' ambush techniques would have failed as grasslands replaced trees. A large number of Neanderthals would have died during these fluctuations, which peaked about 30,000 years ago. When food became scarce, this difference may have played a major role in the Neanderthals' extinction [McKie 2009]. At El Sidrón cave in north western Spain, Neanderthal bones dated to 48,000 years, appear to show signs of cannibalism. At this time, the only hominins in this region of Europe were Neanderthals. Whilst the cut and percussion marks on the bones for the marrow may be conclusive, we still don’t know if this act was one of desperation or veneration.

Kindred is the definitive guide to the Neanderthals. Since their discovery more than 160 years ago, Neanderthals have metamorphosed from the losers of the human family tree to A-list hominins.

Kindred: Neanderthal life, love, death and art by Rebecca Wragg Sykes

- Product details: ISBN-10 : 147293749X

- ISBN-13: 978-1472937490

- Hardcover: 400 pages

- Product Dimensions: 24.1 x 3.8 x 16.2 cm

- Publisher: Bloomsbury Sigma (20 Aug. 2020)

Kindred: Neanderthal life, love, death and art

by Rebecca Wragg Sykes

In Kindred, Rebecca Wragg Sykes uses her experience at the cutting-edge of Palaeolithic research to share our new understanding of Neanderthals, shoving aside clichés of rag-clad brutes in an icy wasteland. She reveals them to be curious, clever connoisseurs of their world, technologically inventive and ecologically adaptable. They ranged across vast tracts of tundra and steppe, but also stalked in dappled forests and waded in the Mediterranean Sea. Above all, they were successful survivors for more than 300,000 years, during times of massive climatic upheaval.

At a time when our species has never faced greater threats, we're obsessed with what makes us special. But, much of what defines us was also in Neanderthals, and their DNA is still inside us. Planning, co-operation, altruism, craftsmanship, aesthetic sense, imagination, perhaps even a desire for transcendence beyond mortality.

About the Author: REBECCA WRAGG SYKES has been fascinated by the vanished worlds of the Pleistocene ice ages since childhood, and followed this interest through a scientific career researching the most enigmatic characters of all, the Neanderthals.

Alongside her academic expertise, Rebecca has earned a reputation for exceptional public communication as a speaker, in print and broadcast. Her writing has featured in the Guardian, Aeon and Scientific American, and she has appeared on history and science programmes for BBC Radio 4. She works as an archaeological and creative consultant, and co-founded the influential TrowelBlazers project, highlighting women in archaeology and the earth sciences.

Bradshaw Foundation - Editor's Review:

Rebecca Wragg Sykes informs us in Kindred that in just 10 years genetics has overtaken archaeology; 'Genetics opened up a world where Neanderthals from different lineages moved across continents.'

Not that archaeologists have been dithering. The forensic analysis described in this book is so thorough, it leaves you with the impression that you actually know Shanidar 1 and Old Man, because as the author states '...we can reconstruct in quite outstanding detail the conditions in which Neanderthals lived at any point in time, and also what the world was like when they disappeared.' Put another way, 'a hand's breadth thickness may be a palimpsest of a thousand summers' and measuring the true number of occupations represented by particular layers is now possible due to ingenious methods such as fuliginochronology. From her book I now see that it's all about the hearth; 'Hearths are archaeological touchstones. They lie at the centre, where the warp of time and weft of space connect....We don't need to see them sitting face to face; we can literally see it in the way artefacts encircle the ashes and the charcoal.' That's why Shanidar 1 and Old Man seem so familiar.

As I began the book I found myself constantly asking myself 'What happened?' This question became louder and louder as Wragg Sykes calmly reveals numerous aspects of the Neanderthal culture, their ingenuity and their adaptability. From the crafted spears and the left-side bones chosen as tools for right-handers at Schöningen to the evidence of composite tools, craft specialisation and collaboration. From the diverse hunting strategies indicated by the variety of habitats and faunal behaviour to the supplementary diets of plants and the use of fire to cook. The author is able to describe organized living spaces as well as a fundamentally nomadic tendency that involved cultural 'exchange'.

'Bruniquel' then turns our attention to 'Beautiful Things'. Two circular forms constructed from stalagmites - over 400 pieces - some 174,000 years ago deep in a cave. As the author points out, 'Bruniquel laughs in the face of austere, survival-only explanations for Neanderthal behaviour.' She proceeds carefully; 'Ascribing any level of formal spirituality to Neanderthals would go far beyond the archaeological evidence, but they too encountered all of life's sensory marvels.' Yes, there is evidence of art. No, it is not representational. But before we analyze that, Wragg Sykes asks us to consider what criteria we are applying to the Neanderthal culture. Take, for example, 'death'; 'Death and its handling have always mattered. Along with art and symbolism, some of the fiercest debates about Neanderthals have concerned what they did with their deceased. Despite advances in the past three decades, and even a newly discovered skeleton, understanding what mortality meant to them is still controversial.' Her analysis of the evidence relating to their grieving process and mortuary traditions makes intriguing reading.

And then came 2010. First we hear about the Denisovans, and then we learn that the first Neanderthal genome showed they had directly contributed to our own ancestry - between 1.8 and 2.6 per cent Neanderthal DNA in everyone except those of sub-Saharan heritage. What follows is fascinating. For example, however they were conceived, how were hybrid children raised to survive? What were the benefits of interbreeding for Homo sapiens in terms of new pathogens encountered whilst on the move? Did this immunity work both ways (or should I say 3 ways) or was there the possibility of a debilitating contagion? Finally, the author asks if there was a 'light-bulb moment' caused by a new genetic mutation which heralded 'more formalised artistic traditions, or flashy burials'?

Kindred is beautifully written, it's convincing, and it's full of surprises. It employs the very latest science to construct a very full and clear picture whilst avoiding over-interpretation. Most importantly, it presents a fascinating story not just of Neanderthals but of ourselves, and we would all do well to pay heed to the sobering thoughts of the Epilogue.