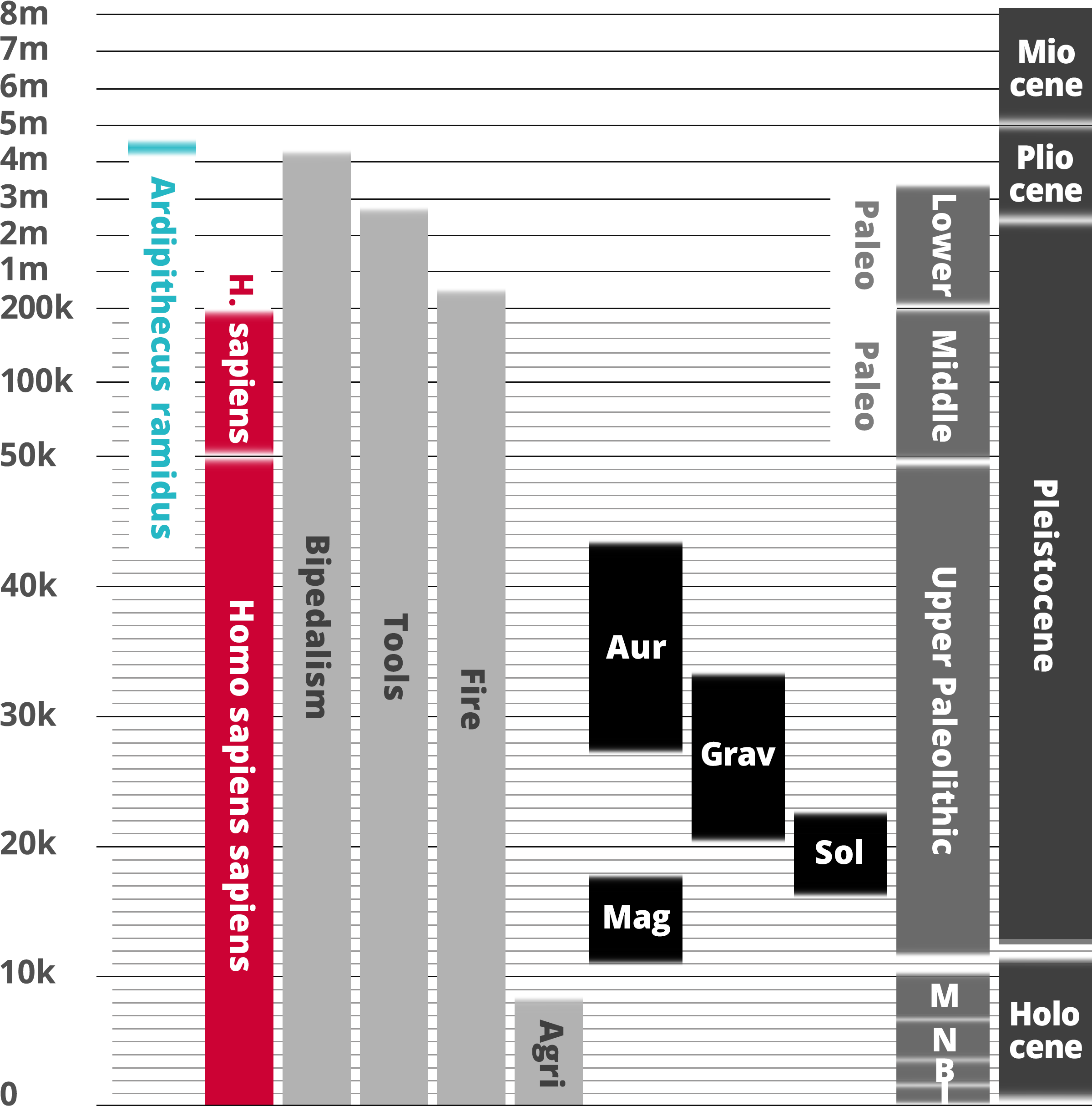

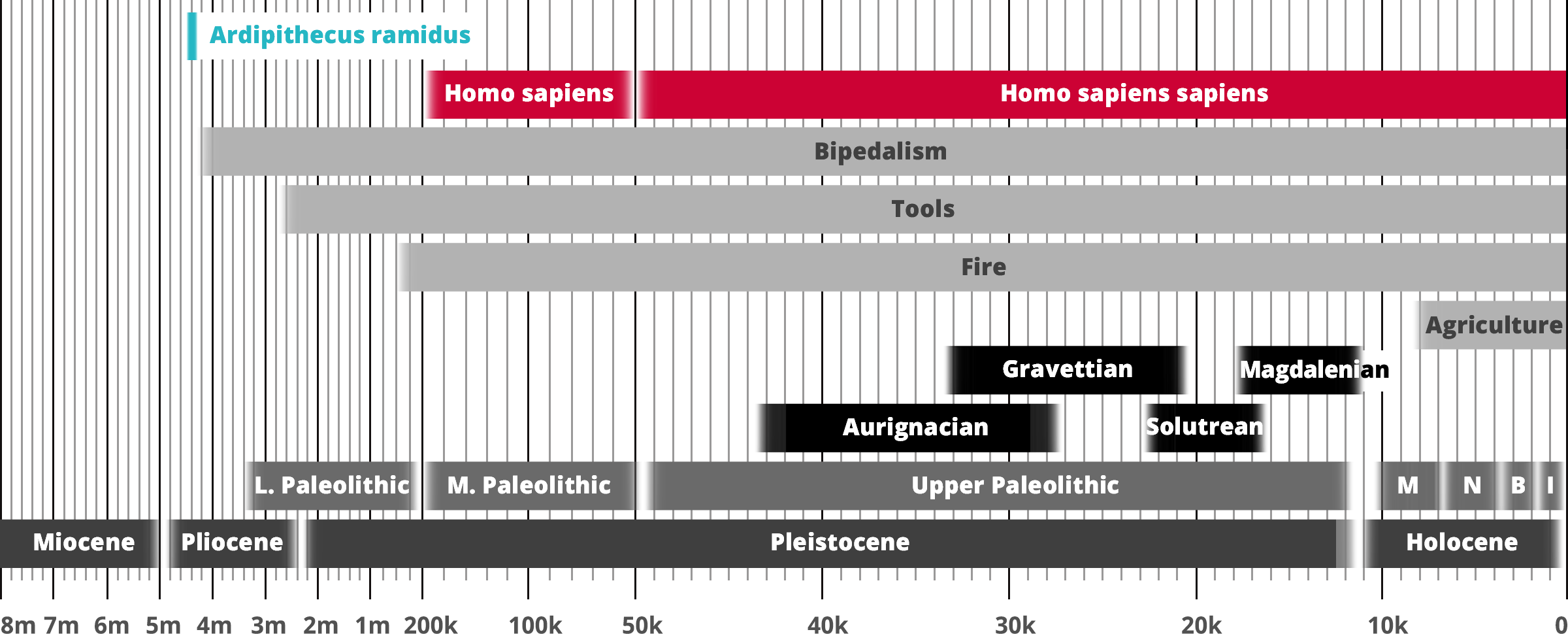

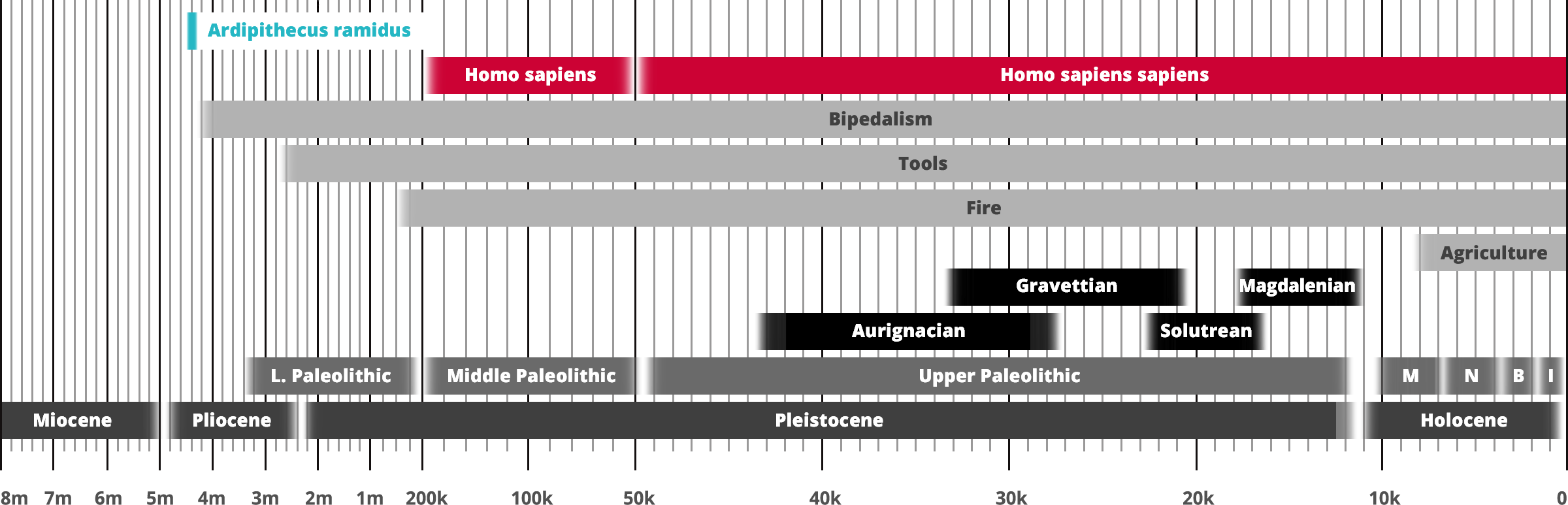

Ardipithecus ramidus

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Period in human prehistory: M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic; B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research and scientific consensus

Ardipithecus ramidus

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Aur = Aurignacian; Mag = Magdalenian;

Grav = Gravettian; Sol = Solutrean

Period in human prehistory:

M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic;

B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research

and scientific consensus

| ARDIPITHECUS RAMIDUS |

|

| Genus: |

Ardipithecus |

| Species: |

Ardipithecus ramidus |

| Other Names: |

Ardi ('Ground' or 'Root') |

| Time Period: |

4.4 million years ago |

| Characteristics: |

Fruit Eater |

| Fossil Evidence: |

Skeletal Bones, Ethiopia, Africa |

Ardipithecus ramidus, nicknamed in 1994 'Ardi' (meaning 'ground' or 'root'), lived about 4.4 million years ago during the early Pliocene. The fossil find was dated on the basis of its stratigraphic position between two volcanic strata. [White, Tim D. et al. 2009]. This fossil was originally described as a species of Australopithecus, but White and his colleagues placed the fossil under a new genus, Ardipithecus.

Tim White's research team discovered the first Ardipithecus ramidus fossils in 1992 in the Afar Depression in the Middle Awash river valley of Ethiopia. More fragments were recovered in 1994, amounting to 45% of the total skeleton. Between 1999 and 2003 a multidisciplinary team led by Sileshi Semaw discovered bones and teeth of nine Ardipithecus ramidus individuals at As Duma in the Gona Western Margin of Ethiopia's Afar region.

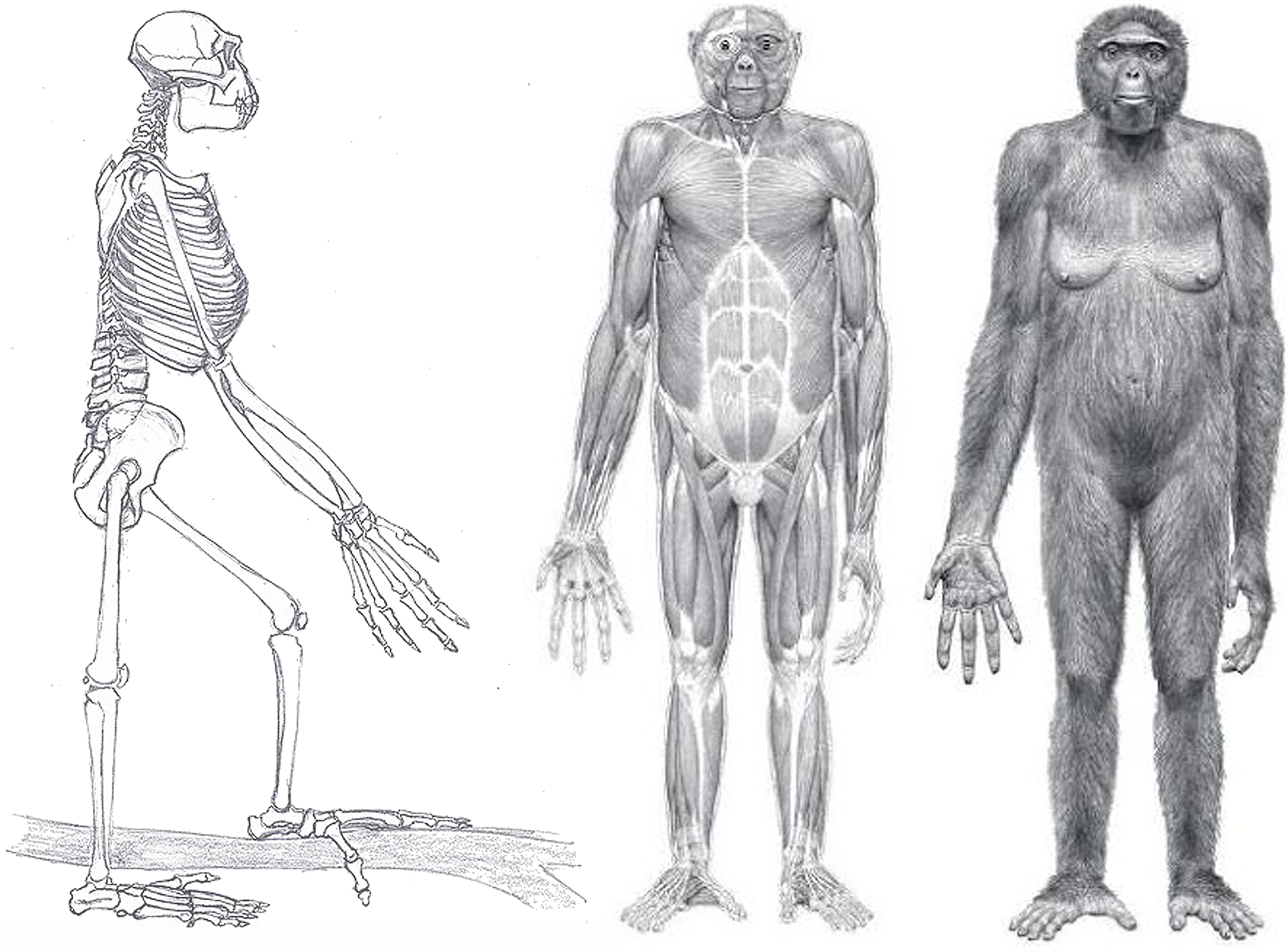

Like most primitive, but unlike all previously recognized hominins, Ardipithecus ramidus had a grasping big toe adapted for locomotion in trees. However, scientists claim that other features of its skeleton reflect adaptation to bipedalism. Like later hominins, Ardipithecus had reduce canine teeth. Its brain was small and comparable in size to that of the modern chimpanzee.

Ardipithecus ramidus had a relatively small brain, measuring between 300 and 350 cm3 similar to that of a chimpanzee, smaller than Australopithecus afarensis 'Lucy' and only 20% the size of the modern Homo sapiens brain.

The teeth suggest it was a fruit eater rather than depending on fibrous plants. In terms of social behaviour, this may have meant relatively little aggression between males and between groups. Ardipithecus ramidus feet are better suited for walking, and may have inhabited an environment of woodland and grasslands with lakes and swamps.

Ardipithecus ramidus - or 'Ardi' - has foot bones which indicate a divergent large toe combined with a rigid foot. This makes it unclear concerning bipedal behavior. The pelvis, reconstructed from a crushed specimen, is said to show adaptations that combine tree-climbing and bipedal activity. The discoverers argue that the ‘Ardi’ skeleton reflects a human-African ape common ancestor that was not chimpanzee-like.

Before the discovery of Ardipithecus and other pre-Australopithecus hominins, it was assumed that the chimpanzee–human last common ancestor and preceding apes appeared much like modern-day chimpanzees, orangutans and gorillas, which would have meant these three changed very little over millions of years. Their discovery led to the postulation that modern great apes, much like humans, evolved several specialized adaptations to their environment, and their ancestors were comparatively poorly adapted to suspensory behavior or knuckle walking, and did not have such a specialized diet.

Also, the origins of bipedality were thought to have occurred due to a switch from a forest to a savanna environment, but the presence of bipedal pre-Australopithecus hominins in woodlands has called this into question, though they inhabited wooded corridors near or between savannas. It is also possible that Ardipithecus and pre-Australopithecus were random offshoots of the hominin line.

Half of the large mammal species associated with A. ramidus at the village of Aramis in the Afar region are spiral-horned antelope and colobine monkeys. There are a few specimens of primitive white and black rhino species, and elephants, giraffes and hippo specimens are less abundant. These animals indicate that Aramis ranged from wooded grasslands to forests, but A. ramidus likely preferred the closed habitats, specifically riverine areas as such water sources may have supported more canopy coverage. Aramis as a whole generally had less than 25% canopy cover. There were exceedingly high rates of scavenging, indicating a highly competitive environment somewhat like Ngorongoro Crater. Predators of the area were the hyenas, the bear, the cats, the dog, and crocodiles. Bayberry, hackberry and palm trees appear to have been common at the time from Aramis to the Gulf of Aden; and botanical evidence suggests a cool, humid climate. Conversely, annual water deficit (the difference between water loss by evapotranspiration and water gain by precipitation) at Aramis was calculated to have been about 1,500 mm, which is seen in some of the hottest, driest parts of East Africa. Carbon isotope analyses of the herbivore teeth from the Gona Western Margin associated with A. ramidus indicate that these herbivores fed mainly on C4 plants and grasses rather than forest plants. The area seems to have featured bushland and grasslands.