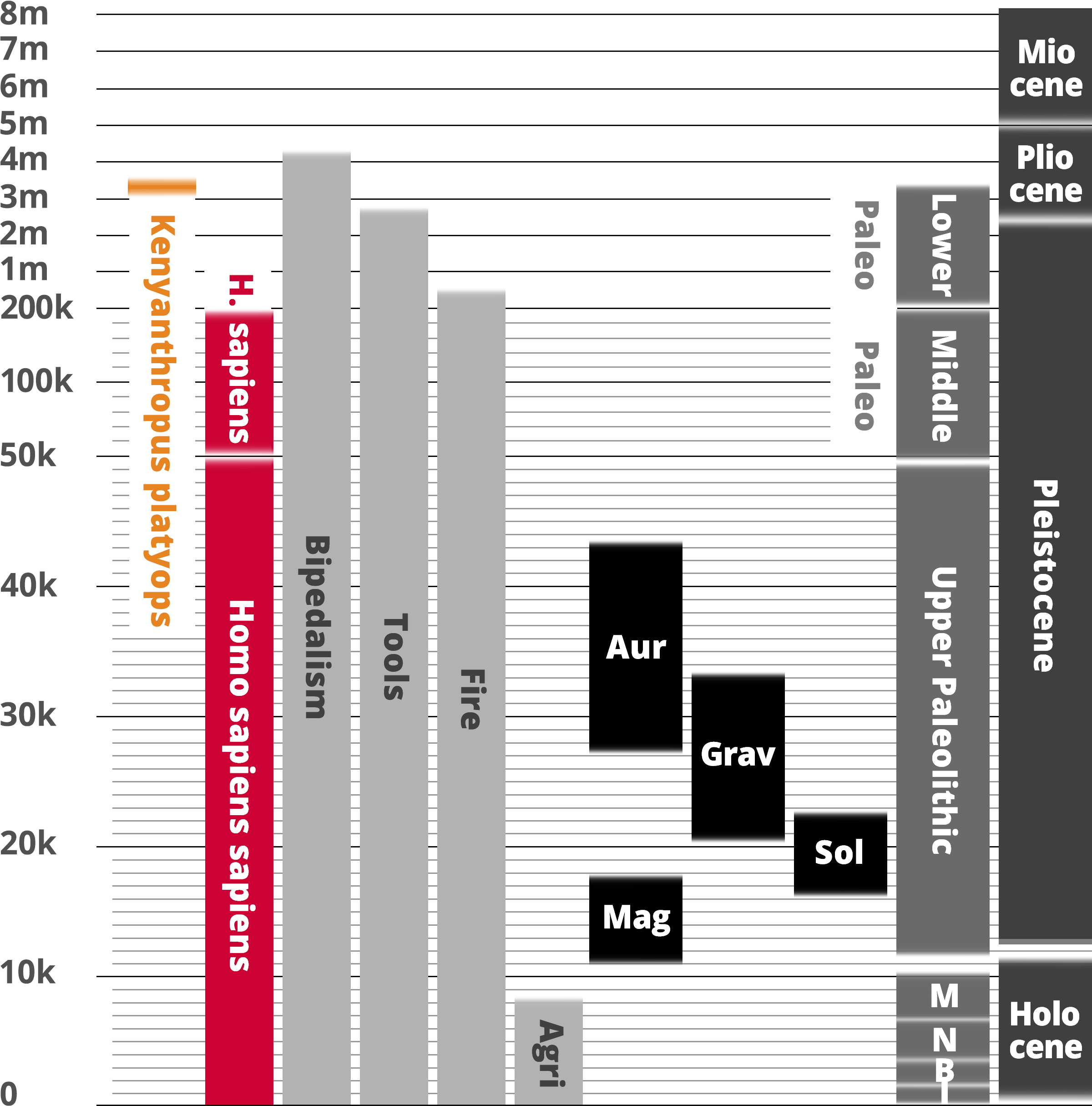

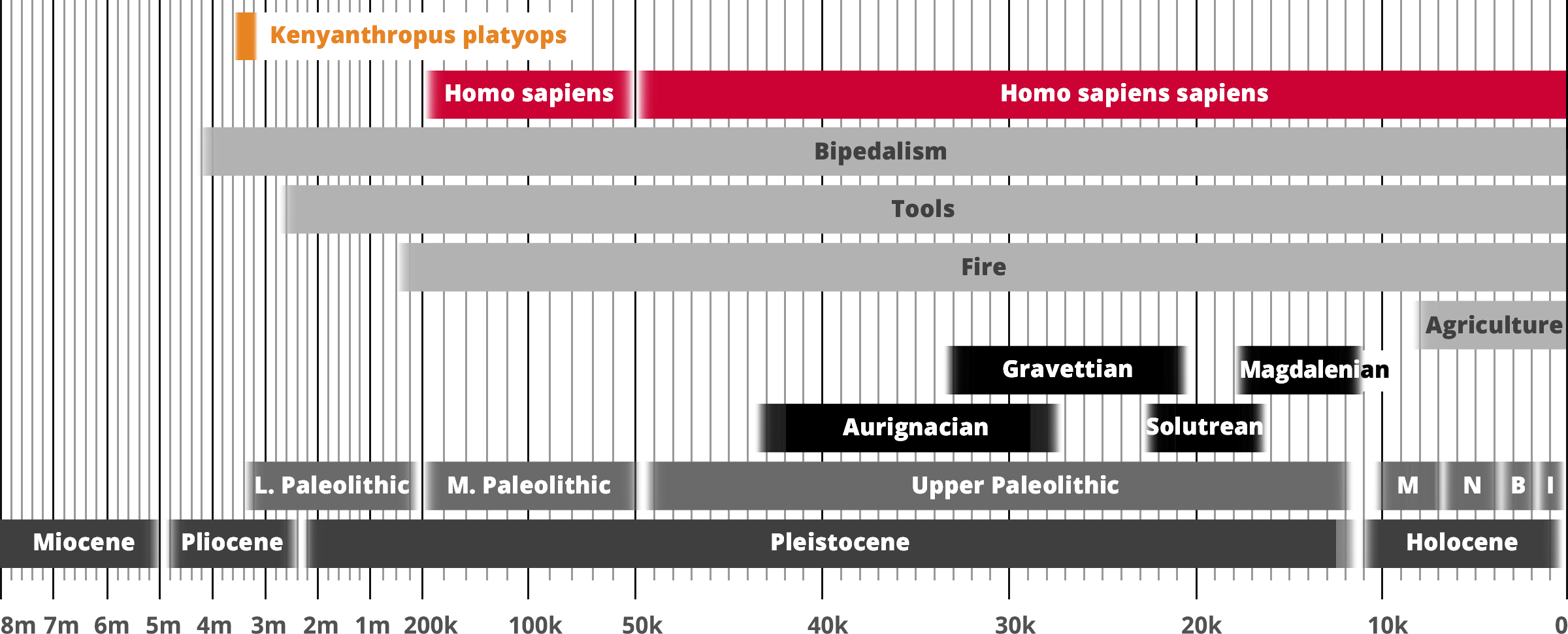

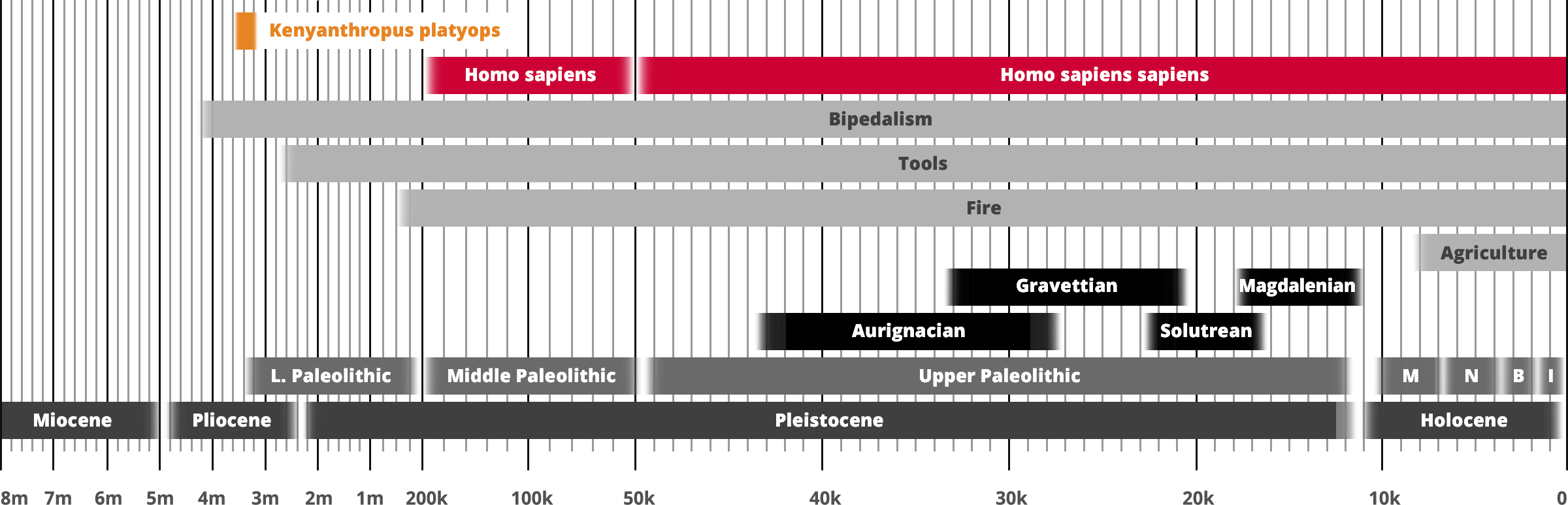

Kenyanthropus platyops

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Period in human prehistory: M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic; B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research and scientific consensus

Kenyanthropus platyops

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Aur = Aurignacian; Mag = Magdalenian;

Grav = Gravettian; Sol = Solutrean

Period in human prehistory:

M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic;

B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research

and scientific consensus

| KENYANTHROPUS PLATYOPS |

|

| Genus: |

Kenyanthropus |

| Species: |

Kenyanthropus platyops |

| Time Period: |

3.5 to 3.2 million years ago |

| Characteristics: |

Bipedal, Flat Face |

| Fossil Evidence: |

Hominin Fossil, Lake Turkana, Kenya, Africa |

Kenyanthropus platyops, meaning 'flat face', is a 3.5 to 3.2 million year old hominin fossil that was discovered in Lake Turkana in Kenya in 1999 by Justus Erus, who was part of Meave Leakey’s team [Leakey 2001].

The flat face, a feature of humans, might represent a bridge between the walking apes and modern humans, although there is controversy over the hominine genus; Leakey suggests the fossil represents an entirely new hominine genus, while others classify it as a separate species of Australopithecus - Australopithecus platyops - and yet others interpret it as an individual of

Australopithecus afarensis. The species remains an enigma, and it supports the view that between 3.5 and 2 million years ago there were several human-like species, each of which were well adapted to life in their particular environments.

The bones discovered at the site included more than 30 skull and tooth fragments. It is the oldest reasonably complete cranium yet discovered. From studying the fossil toe bone it probably walked upright. Teeth are intermediate between typical human and typical ape forms.

According to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, very little is known about Kenyanthropus platyops — the flat-faced, small-brained, bipedal species living about 3.5 million years ago in Kenya. Kenyanthropus inhabited Africa at the same time as Lucy’s species Australopithecus afarensis, and could represent a closer branch to modern humans than Lucy’s on the evolutionary tree. Before the discovery of the only known skull of this species in 1999, the earliest fossil evidence known for a flat-faced early human, a significant shift in skull structure, was around 2 million years ago.

Kenyanthropus is a genus of extinct hominin identified from the Lomekwi site by Lake Turkana, Kenya, dated to 3.3 to 3.2 million years ago during the Middle Pliocene (Source: Wikipdia). It contains one species, K. platyops, but may also include the 2 million year old Homo rudolfensis, or K. rudolfensis. Before its naming in 2001, Australopithecus afarensis was widely regarded as the only australopithecine to exist during the Middle Pliocene, but Kenyanthropus evinces a greater diversity than once acknowledged. Kenyanthropus is most recognisable by an unusually flat face and small teeth for such an early hominin, with values on the extremes or beyond the range of variation for australopithecines in regard to these features. Multiple australopithecine species may have coexisted by foraging for different food items (niche partitioning), which may be reason why these apes anatomically differ in features related to chewing.

The Lomekwi site also yielded the earliest stone tool industry, the Lomekwian, characterised by the rudimentary production of simple flakes by pounding a core against an anvil or with a hammerstone. It may have been manufactured by Kenyanthropus, but it is unclear if multiple species were present at the site or not. The knappers were using volcanic rocks collected no more than 100 m (330 ft) from the site. Kenyanthropus seems to have lived on a lakeside or floodplain environment featuring forests and grasslands.

Depiction of Kenyanthropus platyops

In 2015, French archaeologist Sonia Harmand and colleagues identified the Lomekwian stone-tool industry at the Lomekwi site. The tools are attributed to Kenyanthropus as it is the only hominin identified at the site, but in 2015, anthropologist Fred Spoor suggested that at least some of the indeterminate specimens may be assignable to A. deyiremeda as the two species have somewhat similar maxillary anatomy. At 3.3 million years old, it is the oldest proposed industry. The assemblage comprises 83 cores, 35 flakes, 7 possible anvils, 7 possible hammerstones, 5 pebbles (which may have also been used as hammers), and 12 indeterminant fragments, of which 52 were sourced from basalt, 51 from phonolite, 35 from trachyphonolite (intermediate composition of phonolite and trachyte), 3 from vesicular basalt, 2 from trachyte, and 6 indeterminant. These materials could have originated at a conglomerate only 100 m (330 ft) from the site.

The cores are large and heavy, averaging 167 mm × 147.8 mm × 108.8 mm and 3.1 kg (6.8 lb). Flakes ranged 19 to 205 mm in length, normally shorter than later Oldowan industry flakes. Anvils were heavy, up to 15 kg. Flakes seem to have been cleaved off primarily using the passive hammer technique (directly striking the core on the anvil) and/or the bipolar method (placing the core on the anvil and striking it with a hammerstone). They produced both unifaces (the flake was worked on one side) and bifaces (both sides were worked). Though they may have been shaping cores beforehand to make them easier to work, the knappers more often than not poorly executed the technique, producing incomplete fractures and fissures on several cores, or requiring multiple blows to flake off a piece. Harmand and colleagues suggested such rudimentary skills may place the Lomekwian as an intermediate industry between simple pounding techniques probably used by earlier hominins, and the flaking Oldowan industry developed by Homo.

It is typically assumed that early hominins were using stone tools to cut meat in addition to other organic materials. Wild chimpanzees and black-striped capuchins have been observed to make flakes by accident while using hammerstones to crack nuts on anvils, but the Lomekwi knappers were producing multiple flakes from the same core, and flipped over flakes to work the other side, which speak to the intentionality of their production. In 2016, Spanish archaeologists Manuel Domínguez-Rodrigo and Luis Alcalá argued Harmand and colleagues did not convincingly justify that the tools were discovered in situ, that is, the tools may be much younger and were reworked into an older layer. If the date of 3.3 million years is accepted, then there is a 700,000 year gap between the next solid evidence of stone tools, at Ledi-Geraru associated with the earliest Homo LD 350-1, the Oldowan industry, reported by American palaeoanthropologist David Braun and colleagues in 2019. This gap can either be interpreted as the loss and reinvention of stone tool technology, or preservation bias (that tools from this time gap either did not preserve for whatever reason, or sit undiscovered), the latter implying the Lomekwian evolved into the Oldowan.

Kenyanthropus was contemporary with A. afarensis ("Lucy"). From 4.5 to 4 million years ago, Lake Turkana may have swelled to upwards of 28,000 km2, in comparison to today's 6,400 km2; the lake at what is now the Koobi Fora site possibly sat at minimum 36 m below the surface. Volcanic hills by Lomekwi pushed basalt into the lake sediments. The lake broke up and from 3.6 to 3.2 million years ago, the region was probably characterised by a series of much smaller lakes, each covering no more than 2,500 km2. Similarly, the bovid remains at Lomekwi are suggestive of a wet mosaic environment featuring both grasslands and forests on a lakeside or floodplain. Theropithecus brumpti is the most common monkey at the site as well as the rest of the Turkana Basin at this time; this species tends to live in more forested and closed environments. At the fossiliferous A. afarensis Hadar site in Ethiopia, Theropithecus darti is the most common monkey, which tends to prefer drier conditions conducive to wood- or grassland environments. Leakey and colleagues argued this distribution means Kenyanthropus was living in somewhat more forested environments than more northerly A. afarensis.