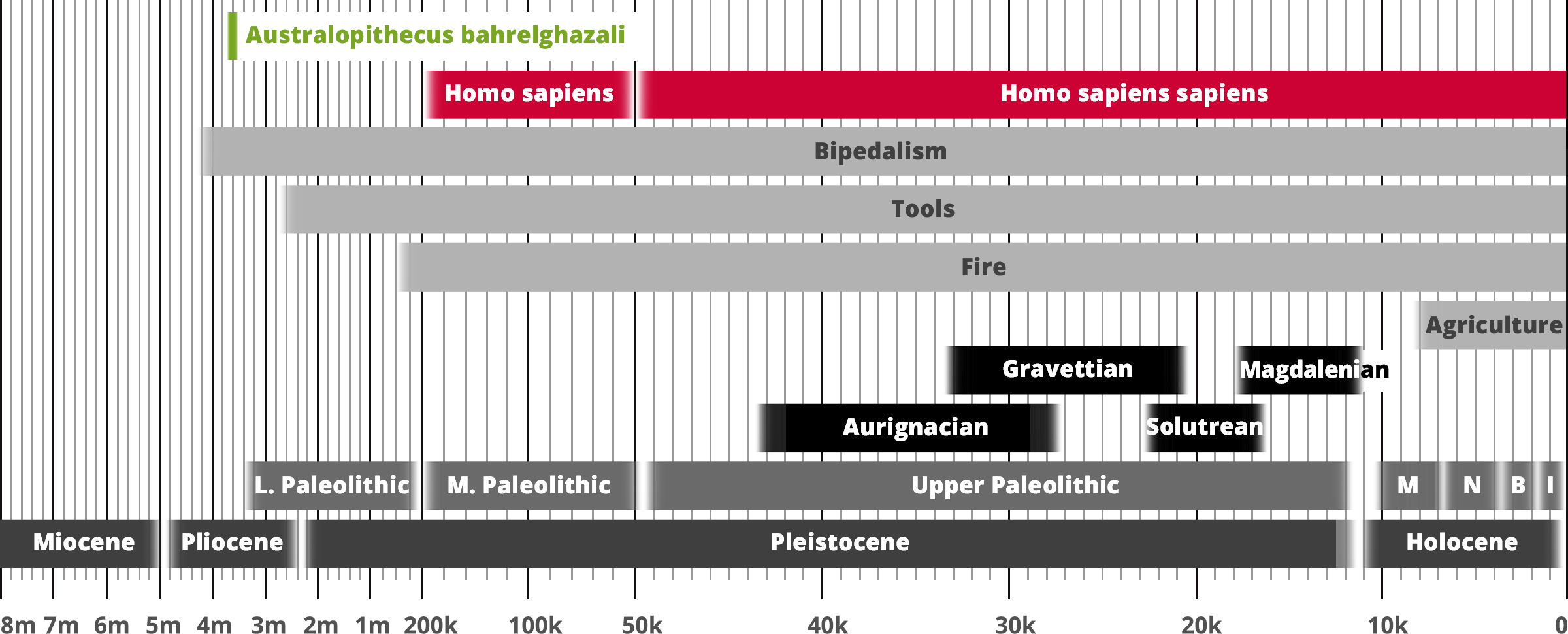

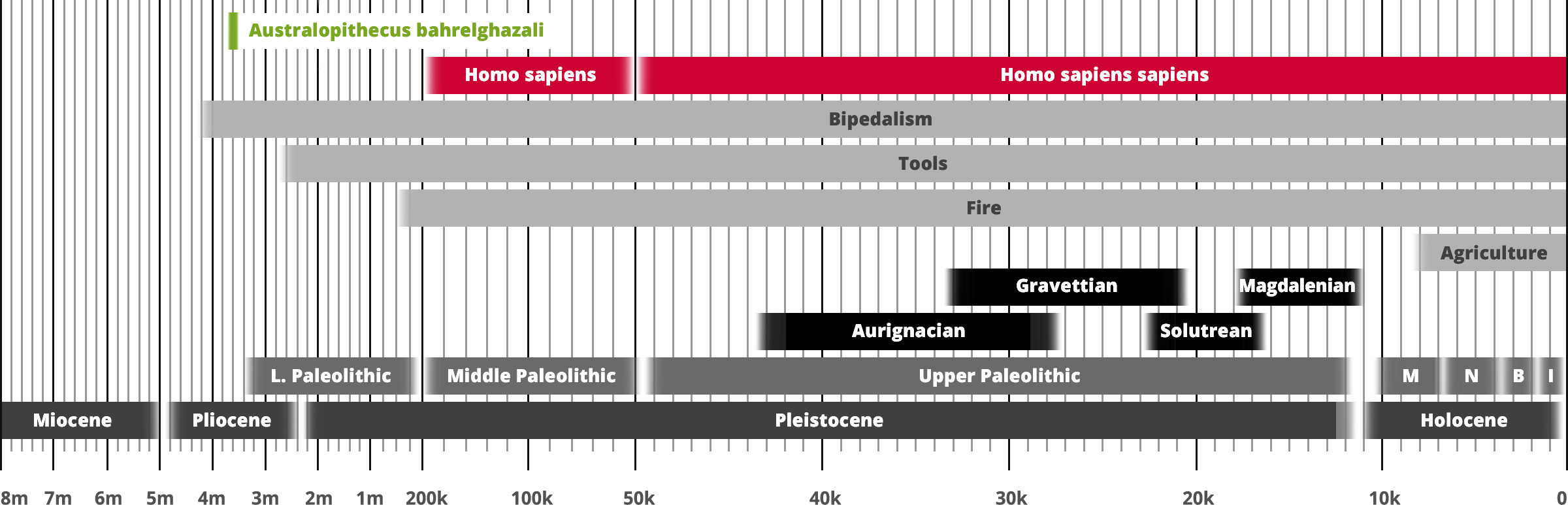

Australopithecus bahrelghazali

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Period in human prehistory: M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic; B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research and scientific consensus

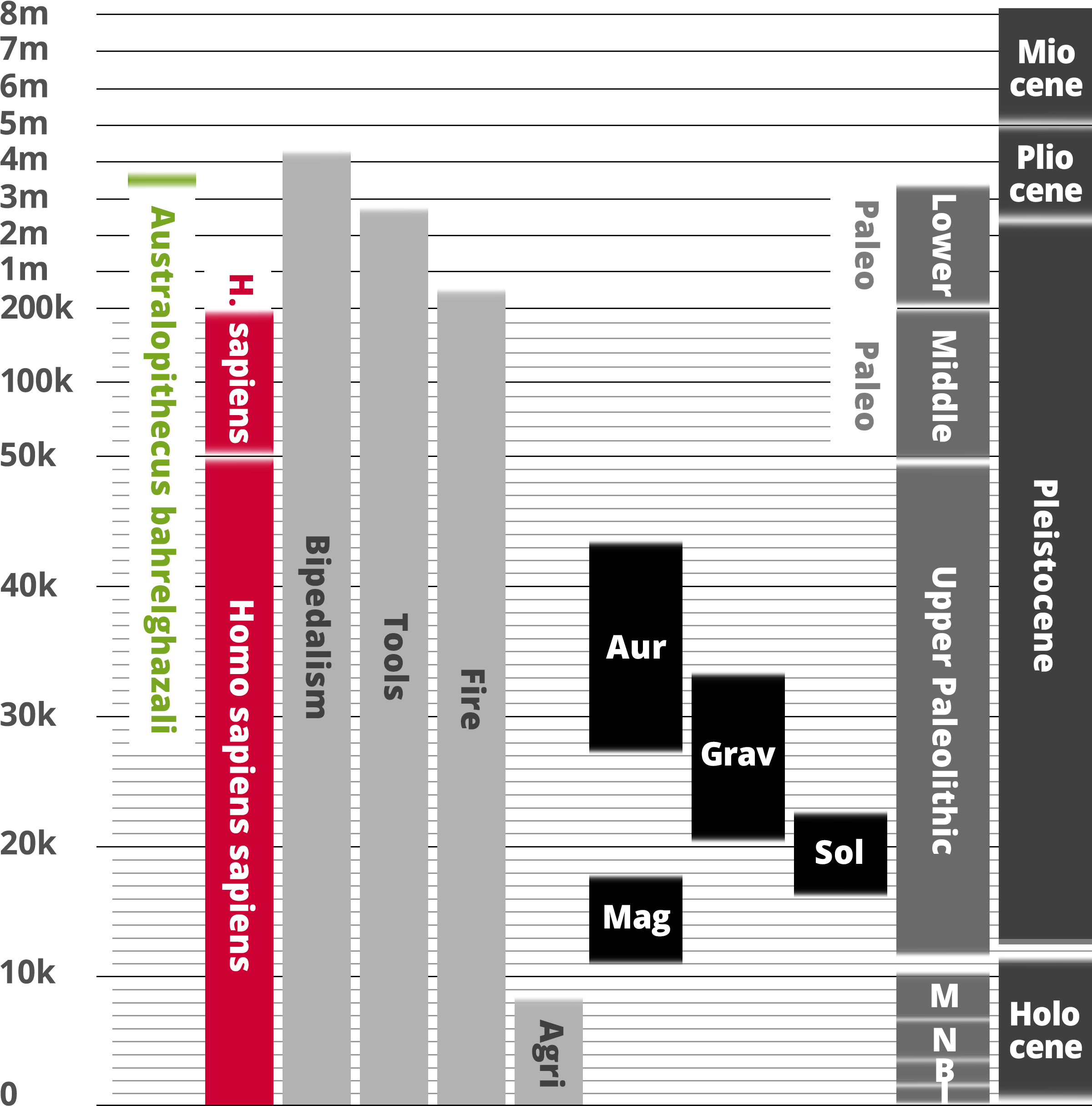

Australopithecus bahrelghazali

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Aur = Aurignacian; Mag = Magdalenian;

Grav = Gravettian; Sol = Solutrean

Period in human prehistory:

M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic;

B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research

and scientific consensus

Australopithecus bahrelghazali

| AUSTRALOPITHECUS BAHRELGHAZALI |

|

| Genus: |

Australopithecus |

| Species: |

Australopithecus bahrelghazali |

| Other Names: |

Abel |

| Time Period: |

3.6 million years ago |

| Characteristics: |

Unknown |

| Fossil Evidence: |

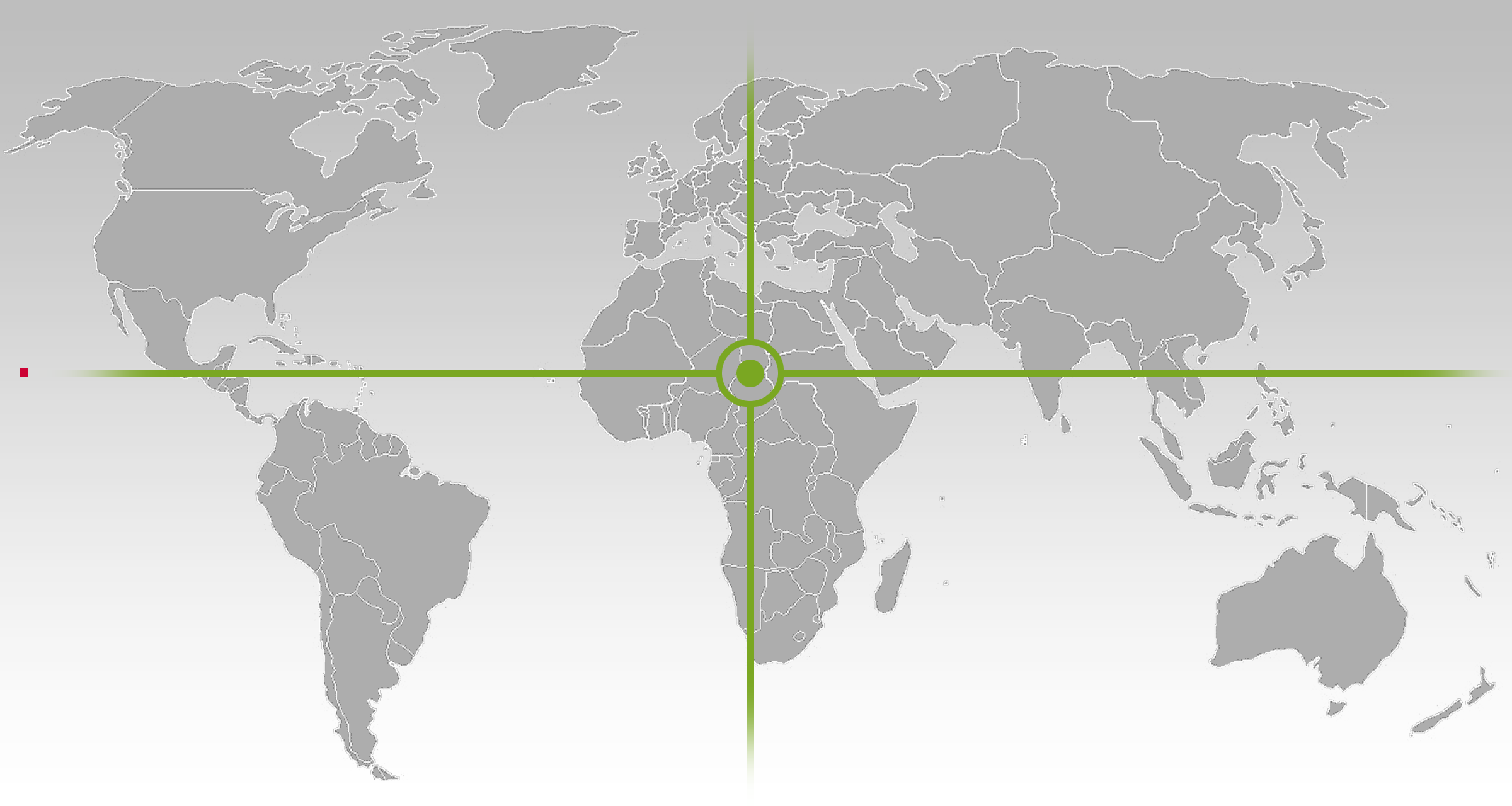

Mandibular Fragment, Chad, Africa |

Australopithecus bahrelghazali is a fossil hominin that was first discovered in 1993 by the paleontologist Michel Brunet in the Bahr el Ghazal valley near Koro Toro in Chad. Australopithecus bahrelghazali was named by Brunet as ‘Abel’. It was dated using Beryllium-based radiometric dating as living approximately 3.6 million years ago [Brunet et al. 2009].

The find consists of a mandibular fragment, a lower second incisor, both lower canines, and all four of its premolars. This is similar to

Australopithecus afarensis, suggesting that Australopithecus bahrelghazali is not a separate species. However, controversy continues as this is the only australopithecine fossil found in Central Africa.

This demonstrates that this group was widely distributed across Africa as opposed to being restricted to East and southern Africa as previously thought. The validity of Australopithecus bahrelghazali has not been widely accepted, in favour of classifying the specimens as

Australopithecus afarensis, a better known Pliocene australopithecine from East Africa, because of the anatomical similarity and the fact that A. bahrelghazali is known only from 3 partial jawbones and an isolated premolar. The specimens inhabited a lakeside grassland environment with sparse tree cover, possibly similar to the modern Okavango Delta, and similarly predominantly ate C4 savanna foods—such as grasses, sedges, storage organs, or rhizomes—and to a lesser degree also C3 forest foods—such as fruits, flowers, pods, or insects. However, the teeth seem ill-equipped to process C4 plants, so its true diet is unclear.

In 1995, two specimens were recovered from Koro Toro, Bahr el Gazel, Chad: KT12/H1 or "Abel" (a jawbone preserving the premolars, canines, and the right second incisor) and KT12/H2 (an isolated first upper premolar). They were discovered by the Franco-Chadian Paleoanthropological Mission, and reported by French palaeontologist Michel Brunet, French geographer Alain Beauvilain, French anthropologist Yves Coppens, French palaeontologist Emile Heintz, Chadian geochemist engineer Aladji Hamit Elimi Ali Moutaye, and British palaeoanthropologist David Pilbeam. Based on the wildlife assemblage, the remains were roughly dated to the middle to late Pliocene 3.5–3 million years ago; consequently, the describers decided to preliminarily assign the remains to

Australopithecus afarensis, which inhabited Ethiopia during that time period, barring more detailed anatomical comparisons. In 1996, they allocated it to a new species, Australopithecus bahrelghazali, naming it after the region; Bahr el Gazel means "River of the Gazelles" in classical Arabic. They denoted KT12/H1 as the holotype and KT12/H2 a paratype. Another jawbone was discovered at the K13 site in 1997, and a third from the KT40 site.

In 2008, a pelite (a type of sedimentary rock) recovered from the same sediments as Abel was radiometrically dated (using the 10Be/9Be ratio) to have been deposited 3.58 million years ago. However, Beauvilain responded that Abel was not found in situ but at the edge of a shallow gulley, and it is impossible to figure out from what stratigraphic section the specimen (or any other fossil from Koro Toro) was first deposited in, in order to accurately radiometrically date it. Nonetheless, Abel was redated in 2010 using the same methods to about 3.65 million years ago, and Brunet agreed with an age of roughly 3.5 million years ago.

Carbon isotope analysis indicates a diet of predominantly C4 savanna foods, such as grasses, sedges, underground storage organs (USOs), or rhizomes. There is a smaller C3 portion which may have comprised more typical ape food items such as fruits, flowers, pods, or insects. This indicates that, like contemporary and future australopiths, Australopithecus bahrelghazali was capable of exploiting whatever food was abundant in its environment, whereas most primates (including savanna chimps) avoid C4 foods. However, despite 55–80% of δ13C deriving from C4 sources similar to

Paranthropus boisei and the modern gelada (and considerably more than any tested

Australopithecus afarensis population), Australopithecus bahrelghazali lacks the specialisations for such a diet. Because the teeth are not hypsodont, it could not have chewed large quantities of grass, and because the enamel is so thin, the teeth would not have been able to withstand the abrasive dirt particles of USOs. In regard to C4 sources, chimps and bonobos (which have even thinner enamel) consume plant medullas as a fallback food and sedges as an important energy and protein source; however a sedge-based diet likely could not have sustained Australopithecus bahrelghazali.

During the Pliocene around the expanded Lake Chad (or "Lake Mega-Chad"), insect trace fossils indicate this was a well-vegetated region, and the abundance of rhizomes may suggest a seasonal climate with wet and dry seasons. Koro Toro has yielded several large mammals, including several antelopes, of which some were endemic, the elephant Loxodonta exoptata, the white rhinoceros Ceratotherium praecox, the pig Kolpochoerus afarensis, a Hipparion horse, a Sivatherium, and a giraffe. Some of these are also known from Pliocene East African sites, implying that animals could freely migrate between east and west of the Great African Rift. The K13 site features, in regard to bovids, an abundance of Reduncinae, Alcelaphinae, and Antilopinae, whereas Tragelaphini is much rarer, which indicates an open environment which was drier than Pliocene East African sites. In total, the area seems to have been predominantly grasslands with some tree cover. In addition, the area featured aquatic creatures, predominantly catfish, and also 10 other kinds of fish, the hippo Hexaprotodon protamphibius, an otter, a Geochelone tortoise, a Trionyx softshell turtle, a false gharial, and an anatid waterbird. These aquatic animals indicate Koro Toro had open-water lakes or streams with swampy grassy margins, connected to the Nilo-Sudan waterways (including the Nile, Chari, Niger, Senegal, Volta, and Gambia Rivers). Koro Toro, during Mega-Chad events (which have been cyclical for the last 7 million years), may have been similar to the modern Okavango Delta.