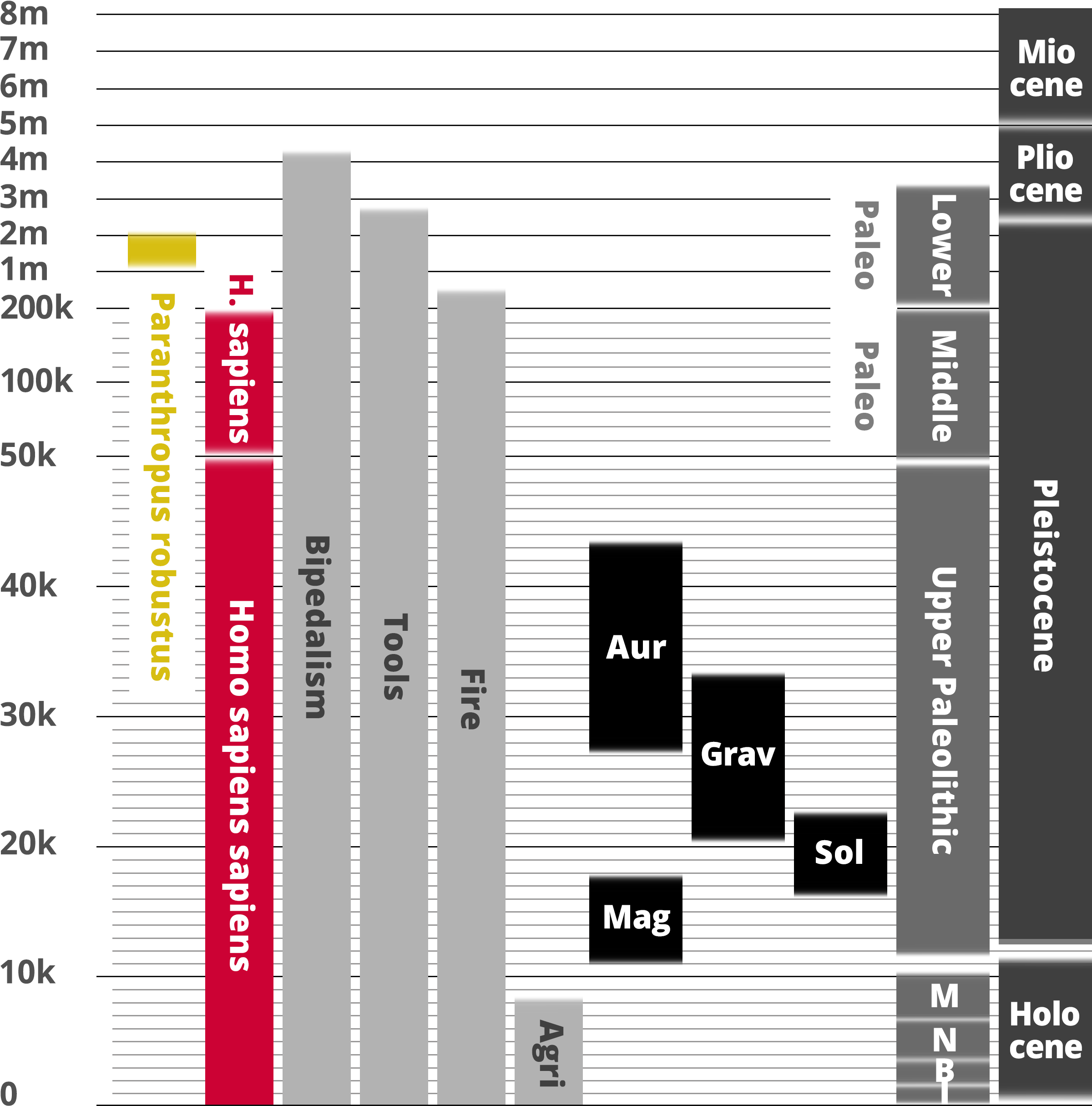

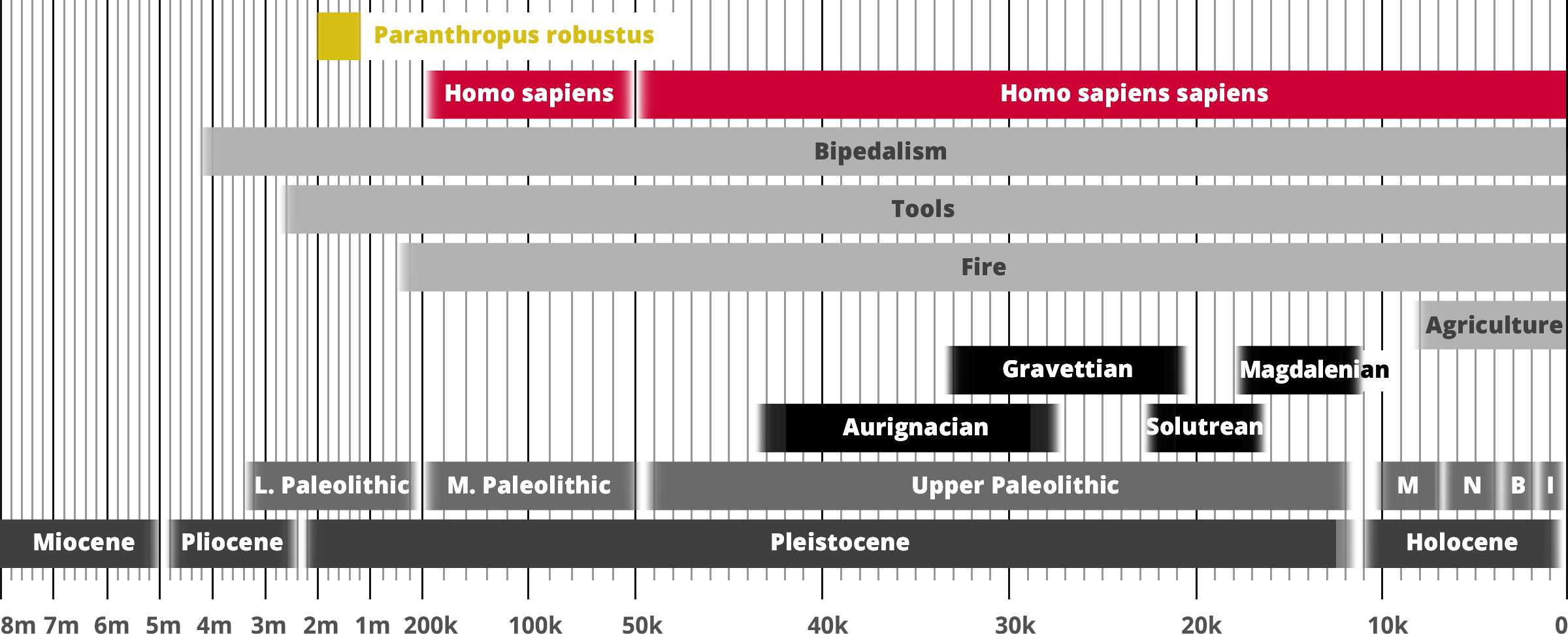

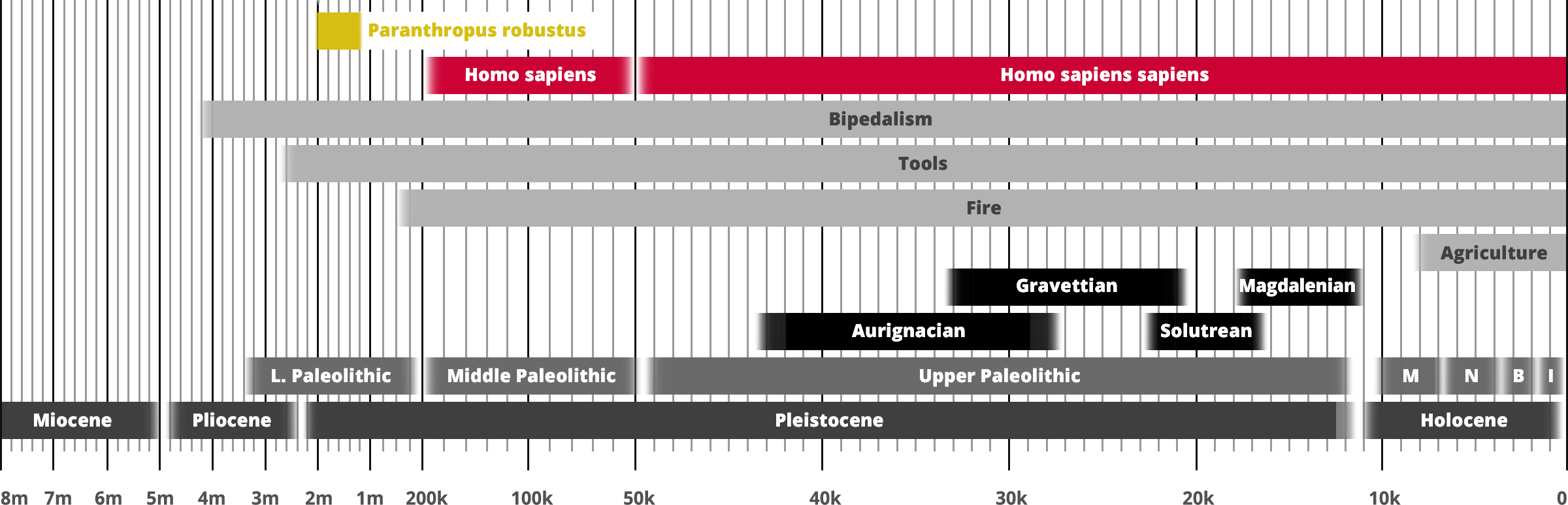

Paranthropus robustus

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Period in human prehistory: M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic; B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research and scientific consensus

Paranthropus robustus

Homo sapiens

Hominin traits

Archaeological industry/Technocomplex including art

Aur = Aurignacian; Mag = Magdalenian;

Grav = Gravettian; Sol = Solutrean

Period in human prehistory:

M = Mesolithic; N = Neolithic;

B = Bronze Age; I = Iron Age;

Geological epoch

* Note: Table based past and current research

and scientific consensus

| PARANTHROPUS ROBUSTUS |

|

| Genus: |

Paranthropus |

| Species: |

Paranthropus robustus |

| Time Period: |

2 to 1.2 million years ago |

| Characteristics: |

Bipedal |

| Fossil Evidence: |

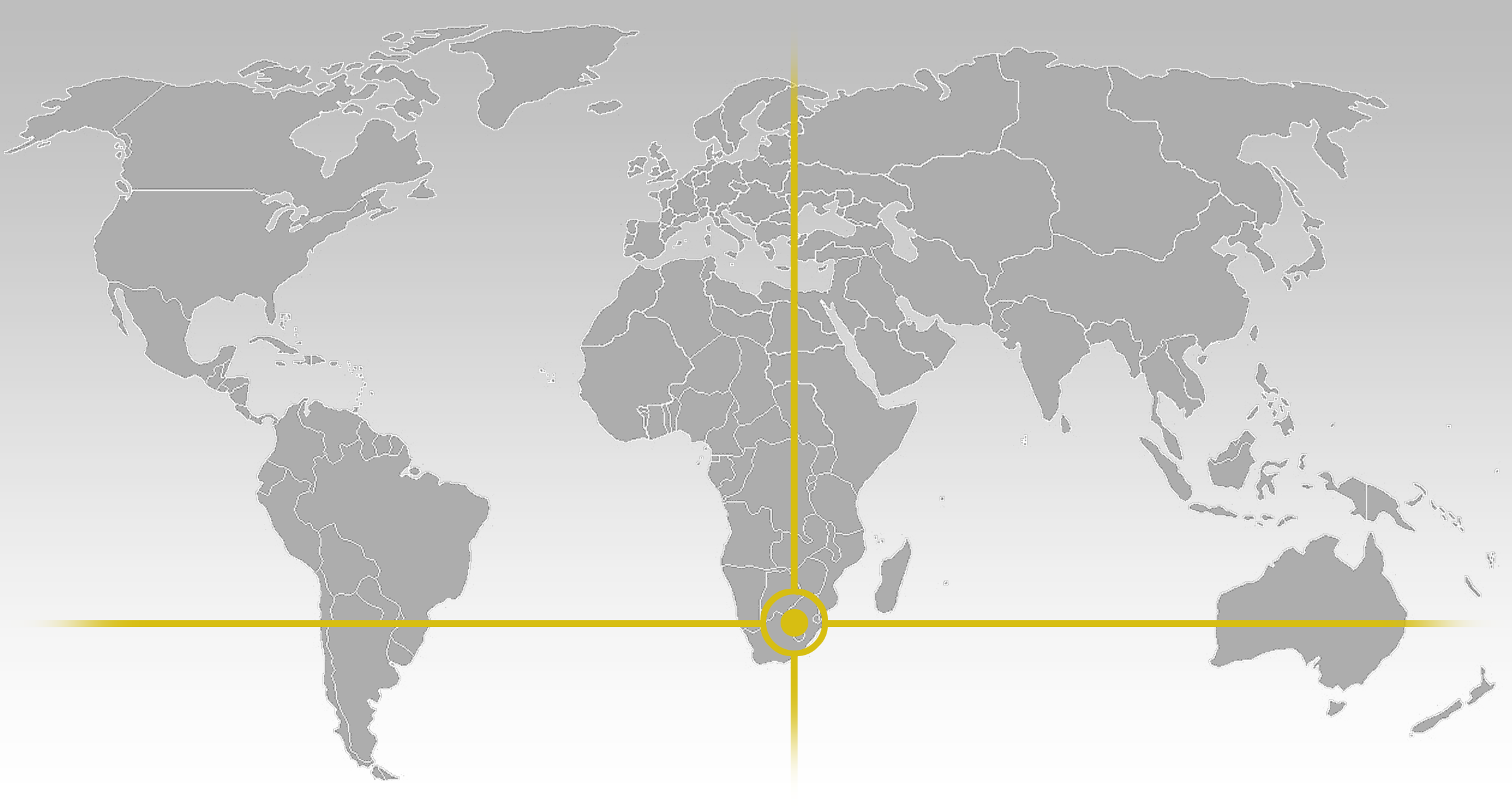

Skull & Teeth Fossils, Kromdraai, South Africa |

Paranthropus robustus (or Australopithecus robustus) was originally discovered at Kromdraai in South Africa in 1938 by the anthropologist Robert Broom. The robust australopithecines, members of the extinct hominin genus Paranthropus were bipedal hominids that probably descended from the gracile australopithecine hominids.

They are characterised by robust craniodental anatomy, including gorilla-like cranial crests, which suggest strong muscles of mastication [Dawkins 2004]. Paranthropus robustus lived between 2 and 1.2 million years ago. Dental studies suggest the average Paranthropus robustus rarely lived past 17 years of age.

Broom's work on the australopithecines showed that the evolution trail leading to Homo sapiens was not just a straight line in the evolutinary tree, but was one of rich diversity.

Paranthropus robustus males may have stood only 1.2m tall and weighed 54 kg while females stood just under 1 meter tall and weighed only 40 kg, indicating a large sexual dimorphism.

The average brain size of measured between 410 and 530 cc, about as large as a chimpanzee. The diet would have been gritty foods such as nuts and tubers, gathered from their environment of open woodland and savanna.

Robust australopithecines - as opposed to gracile australopithecines - are characterised by heavily built skulls capable of producing high stresses and bite forces, as well as inflated cheek teeth (molars and premolars). Males had more heavily built skulls than females. Paranthropus robustus may have had a genetic susceptibility for pitting enamel hypoplasia on the teeth, and seems to have had a dental cavity rate similar to non-agricultural modern humans. The species is thought to have exhibited marked sexual dimorphism, with males substantially larger and more robust than females.

Paranthropus robustus seems to have consumed a high proportion of C4 savanna plants. In addition, it may have also eaten fruits, underground storage organs (such as roots and tubers), and perhaps honey and termites. Paranthropus robustus may have used bones as tools to extract and process food. It is unclear if P. robustus lived in a harem society like gorillas or a multi-male society like baboons. Paranthropus robustus society may have been patrilocal, with adult females more likely to leave the group than males, but males may have been more likely to be evicted as indicated by higher male mortality rates and assumed increased risk of predation to solitary individuals. Paranthropus robustus contended with sabertooth cats, leopards, and hyenas on the mixed, open-to-closed landscape, and Paranthropus robustus bones probably accumulated in caves due to big cat predation. It is typically found in what were mixed open and wooded environments, and may have gone extinct in the Mid-Pleistocene Transition characterised by the continual prolonging of dry cycles and subsequent retreat of such habitat.

The genus Paranthropus (otherwise known as "robust australopithecines", in contrast to the "gracile australopithecines") now also includes the East African

Paranthropus boisei and

Paranthropus aethiopicus. It is still debated if this is a valid natural grouping (monophyletic) or an invalid grouping of similar-looking hominins (paraphyletic). Because skeletal elements are so limited in these species, their affinities with each other and with other australopithecines are difficult to gauge with accuracy. The jaws are the main argument for monophyly, but jaw anatomy is strongly influenced by diet and environment, and could have evolved independently in Paranthropus robustus and

Paranthropus boisei. Proponents of monophyly consider

Paranthropus aethiopicus to be ancestral to the other two species, or closely related to the ancestor. Proponents of paraphyly allocate these three species to the genus Australopithecus as

Paranthropus boisei,

Paranthropus aethiopicus, and A. robustus. In 2020, palaeoanthropologist Jesse M. Martin and colleagues' phylogenetic analyses reported the monophyly of Paranthropus, but also that P. robustus had branched off before

Paranthropus aethiopicus (that

Paranthropus aethiopicus was ancestral to only

Paranthropus boisei). The exact classification of Australopithecus species with each other is quite contentious.

An artist's interpretation of Paranthropus robustus

Cave sites in the Cradle of Humankind often have stone and bone tools, with the former attributed to early Homo and the latter generally to Paranthropus robustus, as bone tools are most abundant when Paranthropus robustus remains far outnumber Homo remains. Australopithecine bone technology was first proposed by Dart in the 1950s with what he termed the "osteodontokeratic culture", which he attributed to

Australopithecus africanus at Makapansgat dating to 3–2.6 million years ago. These bones are no longer considered to have been tools, and the existence of this culture is not supported. The first probable bone tool was reported by Robinson in 1959 at Sterkfontein Member 5. Excavations led by South African palaeontologist Charles Kimberlin Brain at Swartkrans in the late 1980s and early 1990s recovered 84 similar bone tools, and excavations led by Keyser at Drimolen recovered 23. These tools were all found alongside Acheulean stone tools, except for those from Swartkrans Member 1 which bore Oldowan stone tools. Thus, there are 108 bone tool specimens from the region in total, and possibly an additional two from Kromdraai B. The two stone tools (either "Developed Oldowan" or "Early Acheulean") from Kromdraai B could possibly be attributed to P. robustus, as Homo has not been confidently identified in this layer, though it is possible that the stone tools were reworked (moved into the layer after the inhabitants had died). Bone tools may have been used to cut or process vegetation, process fruits (namely marula fruit), strip tree bark, or dig up tubers or termites. The form of Paranthropus robustus incisors appears to be intermediate between

Homo erectus and

modern humans, which could possibly mean it did not have to regularly bite off mouthfuls of a large food item due to preparation with simple tools. The bone tools were typically sourced from the shaft of long bones from medium- to large -sized mammals, but tools sourced from mandibles, ribs, and horn cores have also been found. They were not manufactured or purposefully shaped for a task, but since they display no weathering, and there is a preference displayed for certain bones, raw materials were likely specifically hand picked. This contrasts with East African bone tools which appear to have been modified and directly cut into specific shapes before using.

In 1988, Brain and South African archaeologist A. Sillent analysed the 59,488 bone fragments from Swartkrans Member 3, and found that 270 had been burnt, mainly belonging to medium-sized antelope, but also zebra, warthog, baboon, and Paranthropus robustus. They were found across the entire depth of Member 3, so fire was a regular event throughout its deposition. Based on colour and structural changes, they found that 46 were heated to below 300 °C, 52 to 300–400 °C, 45 to 400–500 °C, and 127 above this. They concluded that these bones were, "the earliest direct evidence of fire use in the fossil record," and compared the temperatures with those achieved by experimental campfires burning white stinkwood which commonly grows near the cave. Though some bones had cut marks consistent with butchery, they said it was also possible hominins were making fire to scare away predators or for warmth instead of cooking. Because both P. robustus and

Homo ergaster/

Homo erectus were found in the cave, they were unsure which species to attribute the fire to. As an alternative to hominin activity, because the bones were not burnt inside the cave, it is possible that they were naturally burnt in cyclically occurring wildfires (dry savanna grass as well as possible guano or plant accumulation in the cave may have left it susceptible to such a scenario), and then washed into what would become Member 3. The now-earliest claim of fire usage is 1.7 million years ago at Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa, made by South African archaeologist Peter Beaumont in 2011, which he attributed to

Homo ergaster/

Homo erectus.