An article by Dalya Alberge on theguardian.com - Vast neolithic circle of deep shafts found near Stonehenge - reports on the discovery of a circle of deep shafts near the world heritage site of Stonehenge which archaeologists are describing as the largest prehistoric structure ever found in Britain.

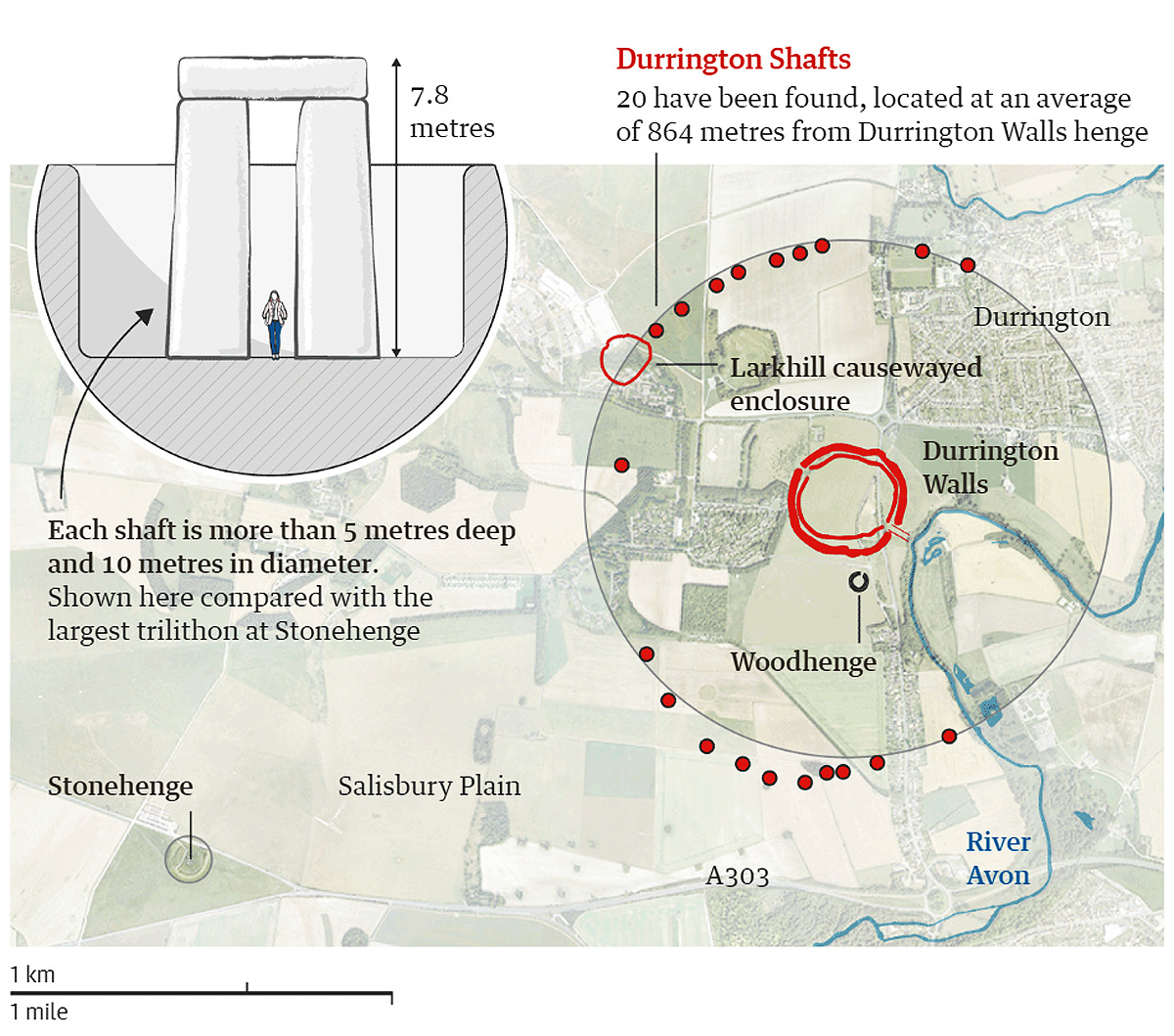

Archaeologists are calling this prehistoric structure, spanning 1.2 miles in diameter, a masterpiece of engineering. Four thousand five hundred years ago, the Neolithic peoples who constructed Stonehenge also dug a series of shafts aligned to form a circle. The structure appears to have been a boundary guiding people to a sacred area because Durrington Walls, one of Britain’s largest henge monuments, is located precisely at its centre. The site is 1.9 miles north-east of Stonehenge in Wiltshire, England.

Professor Vincent Gaffney, a leading archaeologist on the project, said: “This is an unprecedented find of major significance within the UK. Key researchers on Stonehenge and its landscape have been taken aback by the scale of the structure and the fact that it hadn’t been discovered until now so close to Stonehenge.”

The Durrington Shafts discovery, announced on Monday, is all the more extraordinary because it offers the first evidence that the early inhabitants of Britain, mainly farming communities, had developed a way to count. Constructing something of this size with such careful positioning of its features could only have been done by tracking hundreds of paces.

The shafts are vast, each more than 5 metres deep and 10 metres in diameter. Approximately 20 have been found and there may have been more than 30. About 40% of the circle is no longer available for study as a consequence of modern development.

Gaffney said: “The size of the shafts and circuit surrounding Durrington Walls is currently unique. It demonstrates the significance of Durrington Walls Henge, the complexity of the monumental structures within the Stonehenge landscape, and the capacity and desire of Neolithic communities to record their cosmological belief systems in ways, and at a scale, that we had never previously anticipated. I can’t emphasise enough the effort that would have gone in to digging such large shafts with tools of stone, wood and bone.”

While Stonehenge was positioned in relation to the solstices, or the extreme limits of the sun’s movement, Gaffney said the newly discovered circular shape suggests a “huge cosmological statement and the need to inscribe it into the earth itself. Stonehenge has a clear link to the seasons and the passage of time, through the summer solstice. But with the Durrington Shafts, it’s not the passing of time, but the bounding by a circle of shafts which has cosmological significance.” The boundary may have guided people towards a sacred site within its centre or warned against entering it.

As the area around Stonehenge is among the world’s most-studied archaeological landscapes, the discovery is all the more unexpected. Having filled naturally over millennia, the shafts – although enormous – had been dismissed as natural sinkholes and dew ponds. The latest technology – including geophysical prospection, ground-penetrating radar and magnetometry – showed them as geophysical anomalies and revealed their true significance.

Coring of the shafts has provided crucial radiocarbon dates to more than 4,500 years ago, making the boundary contemporary with both Stonehenge and Durrington Walls. The boundary also appears to have been laid out to include an earlier prehistoric monument, the Larkhill causewayed enclosure, built more than 1,500 years before the henge at Durrington. Struck flint and unidentified bone fragments were recovered from the shafts, but archaeologists can only speculate how those features were once used.

Gaffney explains that “What we’re seeing is two massive monuments with their territories. Other archaeologists, including Michael Parker Pearson at University College London, have suggested that, while Stonehenge, with its standing stones, was an area for the dead, Durrington, with its wooden structures, was for the living.”

He added that, while numerous ancient civilisations had counting systems, the evidence lies primarily in texts in various forms that they left behind. The planning involved in contracting a prehistoric structure of this size must have involved a tally or counting system, he believes. Positioning each shaft would have involved pacing more than 800 metres from the henge outwards.

The research has involved a consortium of archaeologists, led by the University of Bradford and including the universities of Birmingham and St Andrews, in an international collaboration with the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology at the University of Vienna. Henry Chapman, professor of archaeology at Birmingham University, described it as “an incredible new monument”, and Richard Bates, a geoscientist at St Andrews University, said it offered “an insight to the past that shows an even more complex society than we could ever imagine”.

The consortium is publishing a scientific open-access paper in Internet Archaeology.

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 22 May 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 10 November 2023

Friend of the Foundation