An article by Derek Hodgson and Paul Pettitt published on The Conversation - Warning signs: how early humans first began to paint animals - reports on new research about why figurative art, in the form of the naturalistic animal depictions appeared relatively suddenly around 37,000 years ago.

Painting from El Castillo cave (Cantabria, Spain). Early Upper Palaeolithic or older. Credit: Becky Harrison and courtesy Gobierno de Cantabria., Author provided.

Visual culture, and the associated forms of symbolic communication, are regarded by palaeo-anthropologists as perhaps the defining characteristic of the behaviour of Homo sapiens. But why did figurative art, in the form of the naturalistic animal depictions - sculpted, painted and engraved - appear relatively suddenly around 37,000 years ago?

Moreover, what did the art mean to its Ice Age hunter-gatherer creators, since modern theories often say more about modern preconceptions regarding the function of art?

In a radical new approach to the issue, the authors applied recent findings from visual neuroscience, perceptual psychology and the archaeology of cave art, and in the hope that it can be tested scientifically.

This hand stencil has been deliberately placed so its left side matches with a natural crack in the wall of El Castillo cave. Credit: Paul Pettitt and courtesy Gobierno de Cantabria., Author provided.

Hands - the first clue comes from the ancient hand marks (positive prints and negative stencils), which predate the earliest animal depictions by a considerable period. Recent dating shows that they were created by Neanderthals more than 64,000 years ago.

Natural cave features - the second clue comes from the widespread inclusion of natural cave features - such as ledges and cracks - as parts of animal depictions.

The environment - the third clue comes from a study of the environment in which Upper Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers, along with other predators, were stalking the large herbivores - such as bison, deer and horses - that formed their prey and which often lay hidden in camouflage in the tundra environment.

The authors argue that hand marks initially supplied the idea to archaic humans that a graphic mark could act as a representation, however basic it was. But how could hand marks give rise to the more complex animal depictions?

Why did figurative art, in the form of the naturalistic animal depictions - sculpted, painted and engraved - appear relatively suddenly around 37,000 years ago?https://t.co/Gr17Cs1gjV #RockArt #archaeology #Chauvet pic.twitter.com/FdYWEwh7cw

— Bradshaw Foundation (@BradshawFND) May 8, 2018

The interior of the cave at Castillo in Spain. Credit: Gabinete de Prensa del Gobierno de Cantabria, CC BY-SA.

The way hunters relate to the environment has changed little since early times in that they remain acutely sensitive to particular animal contours. Moreover, in challenging lighting situations - and where prey might be well camouflaged - it is better to "see" an animal when it's not there - to mistake a rock for a bear - than not see it. This is a cognitive adaptation that promotes survival. In dangerous conditions, the human visual system becomes increasingly aroused and is even more easily triggered into accepting the slightest cue as an animal.

The authors argue that we are preconditioned to interpret ambiguous shapes as animals. Recent evidence from visual neuroscience shows that when individuals are conditioned to see particular objects such as faces they are more likely to see them in ambiguous patterns. Upper Palaeolithic hunters conditioned themselves due to the need to detect animals, but this effect was reinforced by the suggestive features of the caves.

In El Castillo cave, this natural stalagmite column bears a boss in the shape of an upright bison, which has been elaborated by painting in black pigment. Credit: Marc Groenen and courtesy Gobierno de Cantabria.

All the hunter needed to do to "complete" a depiction was to add one or two graphic marks to the suggestive natural features based on the visual imagery in their "mind's eye". A typical example of this can be seen at Chauvet cave where two giant deer (Megaloceros) are depicted by complementing the natural wall fissures (highlighted in brown) with lines (highlighted in black) painted onto the cave wall to complete the animal outlines. This potentially explains how the very first representational depictions arose.

This research is being prepared for an academic paper.

Read the full article:

https://theconversation.com/warning-signs-how-early-humans-first-began-to-paint-animals-95597

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 22 May 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 10 November 2023

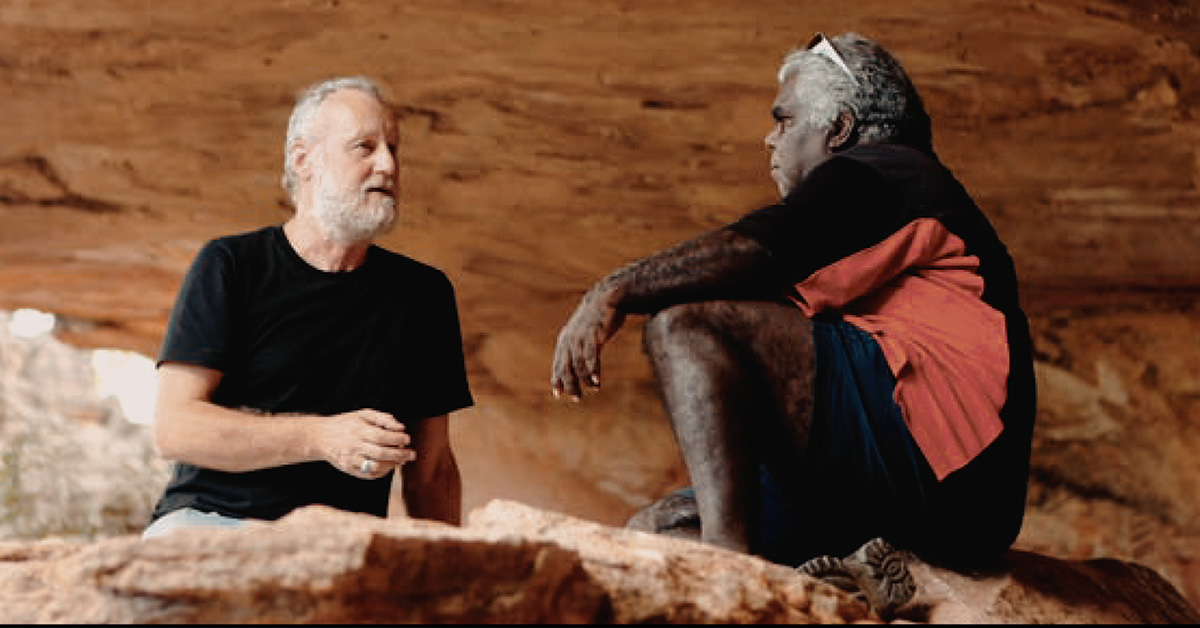

Friend of the Foundation