An article provided by the University of Victoria on phys.org - Archaeology team makes world-first tool discovery - reports on new research published in the Journal of Archaeological Science by a team led by paleoanthropologist April Nowell of the University of Victoria. The research reveals surprisingly sophisticated adaptations by early humans living 250,000 years ago in a former oasis near Azraq, Jordan.

Blade showing positive for rhino protein residue. Image: April Nowell.

The research team from UVic and partner universities in the US and Jordan has found the oldest evidence of protein residue - the residual remains of butchered animals including horse, rhinoceros, wild cattle and duck - on stone tools. The discovery draws startling conclusions about how these 'early humans' subsisted in a very demanding habitat, thousands of years before Homo sapiens first evolved in Africa.

Team in Jordan finds oldest evidence of protein residue on stone tools #paleoanthropology https://t.co/PGExfjkJLJ pic.twitter.com/M8EmwtXtgS

— Bradshaw Foundation (@BradshawFND) August 9, 2016

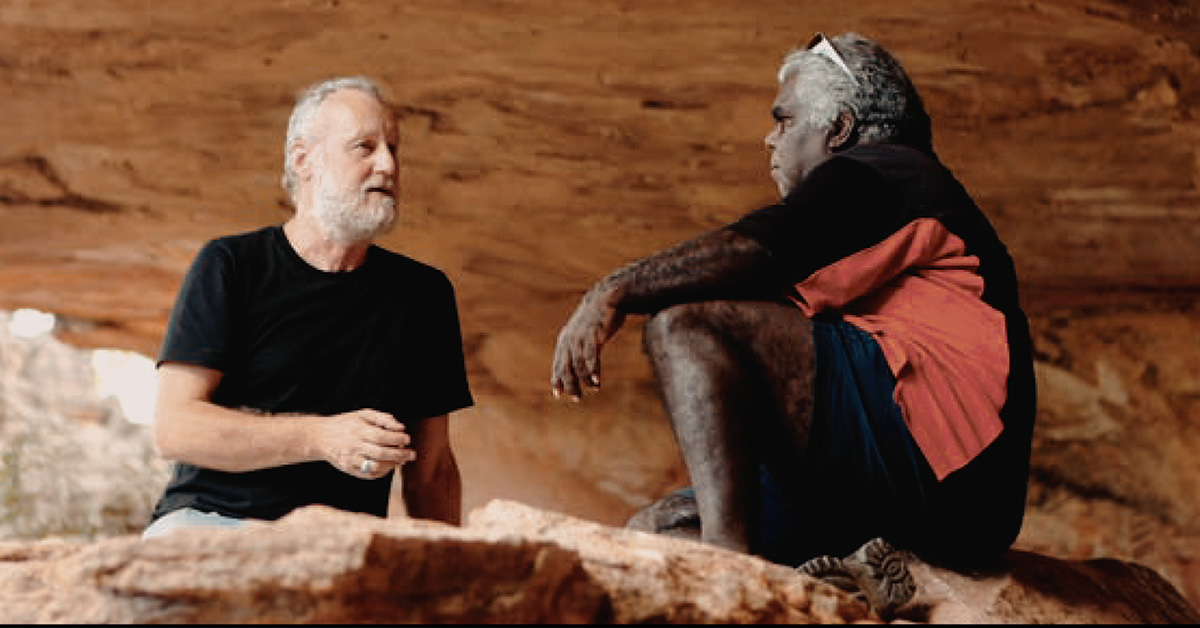

Image: UNIVERSITY OF VICTORIA

The team excavated 10,000 stone tools over three years from what is now a desert in the northwest of Jordan, but was once a wetland that became increasingly arid habitat 250,000 years ago. The team closely examined 7,000 of these tools, including scrapers, flakes, projectile points and hand axes, with 44 subsequently selected as candidates for testing. Of this sample, 17 tools tested positive for protein residue, i.e. blood and other animal products.

Image: UNIVERSITY OF VICTORIA

Nowell states that researchers have known for decades about carnivorous behaviours by tool-making hominins dating back 2.5 million years, but now, for the first time, we have direct evidence of exploitation by our Stone Age ancestors of specific animals for subsistence. The hominins in this region were clearly adaptable and capable of taking advantage of a wide range of available prey, from rhinoceros to ducks, in an extremely challenging environment. This tells us about their lives and complex strategies for survival, such as the highly variable techniques for prey exploitation, as well as predator avoidance and protection of carcasses for food. The picture it creates may be not what was expected.

Moreover, it asks questions about how Middle Pleistocene hominins lived in this region, witha key to understanding the nature of interbreeding and population dispersals across Eurasia with modern humans and archaic populations such as Neanderthals.

Nowell concludes by stating that this research brings a greater understanding of early hominin diets; other researchers with tools as old or older than these tools from sites in a variety of different environmental settings may also have success when applying the same technique to their tools, especially in the absence of animal remains at those sites.

Journal of Archaeological 73 (2016) 36-44

Middle Pleistocene subsistence in the Azraq Oasis, Jordan: Protein residue and other proxies

A. Nowell, C. Walker, C.E. Cordova , C.J.H. Ames, J.T. Pokines, D. Stueber, R. DeWitt, A.S.A. al-Souliman

Abstract

Excavations at Shishan Marsh, a former desert oasis in Azraq, northeast Jordan, reveal a unique ecosystem and provide direct family-specific protein residue evidence of hominin adaptations in an increasingly arid environment approximately 250,000 years ago. Based on lithic, faunal, paleoenvironmental and protein residue data, we conclude that Late Pleistocene hominins were able to subsist in extreme arid environments through a reliance on surprisingly human-like adaptations including a broadened subsistence base, modified tool kit and strategies for predator avoidance and carcass protection.

Visit the ORIGINS section to watch Cassandra Turcotte explain the significance of Palaeolithic stone tools:

http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/origins/oldowan_stone_tools.php

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 23 July 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 29 May 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 03 February 2025

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 30 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 19 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 January 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 21 March 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 07 February 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 19 May 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 14 July 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 22 November 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 12 July 2016

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 26 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 27 November 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 07 October 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 November 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 22 May 2024

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 10 November 2023

Friend of the Foundation