An article on newscientist by Alice Klein - Painted 37,000-year-old shell is East Asia's oldest jewellery - reports on the shell jewellery and ornaments up to 42,000 years old, discovered in East Timor, which have overturned long-held assumptions that the first inhabitants of South-East Asia were culturally unsophisticated.

Shell jewellery as evidence of ancient skills and cultural sophistication. Image: Michelle Langley, Australian National University

The finds represent the oldest evidence of ornament and jewellery-making in the region. The most ancient example of shell jewellery is 82,000 years old and was found in the Grotte des Pigeons at Taforalt, Morocco, although some shell art may date even further back. As humans migrated out of Africa, shell jewellery started appearing in the European archaeological record from about 50,000 years ago.

Shell jewellery and ornaments up to 42,000 years old discovered in East Timorhttps://t.co/bLm4P3BqRa pic.twitter.com/MFyULe2aNO

— Bradshaw Foundation (@BradshawFND) August 19, 2016

Scientists estimate that humans moved into East Asia at about the same time, but the region has yielded few examples of personal ornamentation of such antiquity. Some researchers had speculated that the early settlers were less technologically advanced than their European counterparts.

Jerimalai cave of East Timor. Image: Michelle Langley, Australian National University. Map location. Image: MailOnline

The new findings, by Michelle Langley of the Australian National University in Canberra and her colleagues, have made finds in the Jerimalai cave of East Timor that refute that idea. One was the shell of an Oliva sea snail, dated to 37,000 years, making it the oldest piece of jewellery ever found in the region. A hole in the top of the shell suggests that it was used in a necklace or bracelet. Marks on the side were characteristic of rubbing against adjacent shell beads. Traces of red ochre may have come from contact with body paint. Experiments with modern Oliva shells showed that the natural wear and tear could not have formed the hole.

42,000-year-old worked and pigment-stained Nautilus shell from Jerimalai (Timor-Leste): Evidence for an early coastal adaptation in ISEA

Michelle C. Langley, Sue O'Connor & Elena Piotto

Journal of Human Evolution, DOI: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.04.005

Abstract

In this paper, we describe worked and pigment-stained Nautilus shell artefacts recovered from Jerimalai, Timor-Leste. Two of these artefacts come from contexts dating to between 38,000 and 42,000 cal. BP (calibrated years before present), and exhibit manufacturing traces (drilling, pressure flaking, grinding), as well as red colourant staining. Through describing more complete Nautilus shell ornaments from younger levels from this same site (>15,900, 9500, and 5000?cal. BP), we demonstrate that those dating to the initial occupation period of Jerimalai are of anthropogenic origin. The identification of such early shell working examples of pelagic shell in Island Southeast Asia not only adds to our growing understanding of the importance of marine resources to the earliest modern human communities in this region, but also indicates that a remarkably enduring shell working tradition was enacted in this area of the globe. Additionally, these artefacts provide the first material culture evidence that the inhabitants of Jerimalai were not only exploiting coastal resources for their nutritional requirements, but also incorporating these materials into their social technologies, and by extension, their social systems. In other words, we argue that the people of Jerimalai were already practicing a developed coastal adaptation by at least 42,000 cal. BP.

Langley believes that close similarities with shell beads of a later date found in the same area hint that jewellery-making skills were passed from one generation to the next.

Ornaments made from the shell of Nautilus pompilius, some of which they dated indirectly to as far back as 42,000 year ago, have been found in the same cave, showing traces of drilling, pressure flaking, grinding and staining with red ochre. Moreover, tuna bones of the same age found in the cave suggest a developed knowledge of deep-sea fishing methods.

Ian McNiven of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia suggests that a lack of excavations in East Asia partly explains why fewer relics have been uncovered, compared with archaeological excavation of ice age sites in Europe. For example, a 30,000-year-old shell necklace was recently found in Australia.

The same applies to rock art being discovered in the region; cave paintings dated to a minimum age of almost 40,000 years has been discovered in the Maros region of southern Sulawesi, Indonesia:

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 24 November 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 27 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 08 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 July 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 June 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 11 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 02 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 16 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 06 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 16 March 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 24 November 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 27 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 08 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 July 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 June 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 11 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 02 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 16 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 06 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 16 March 2021

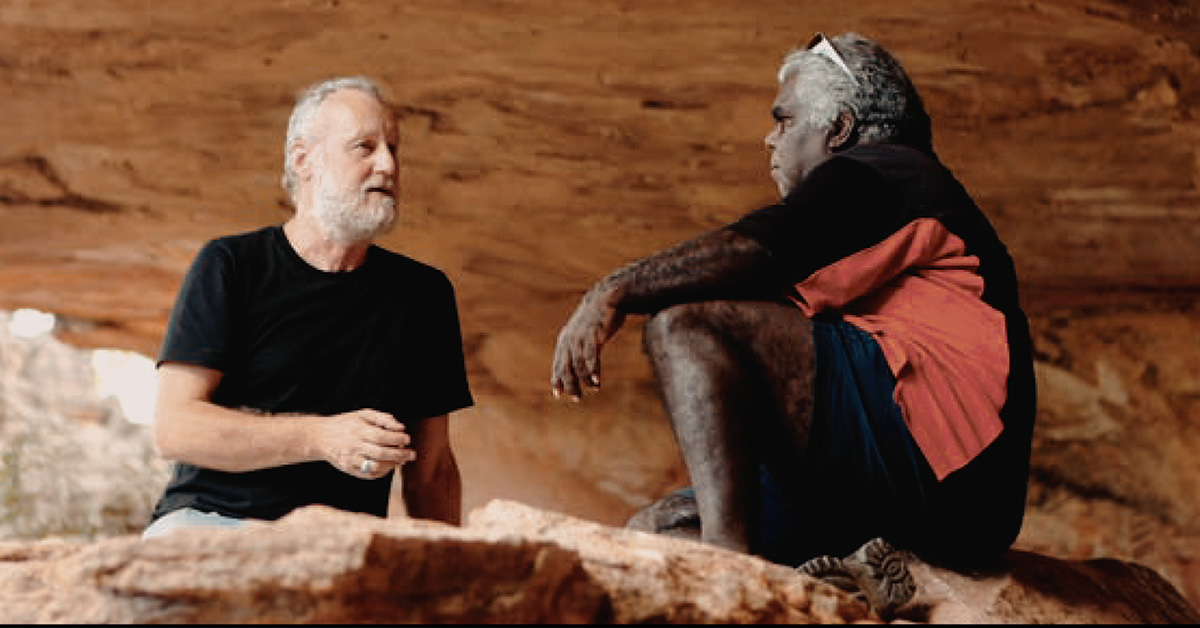

Friend of the Foundation