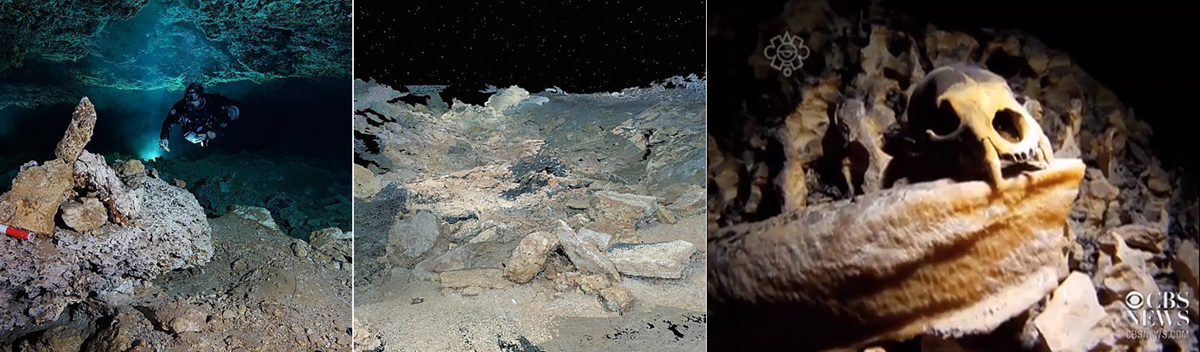

An article on cbsnews.com - 'Divers find evidence of America's first mines — and skeletons — in underwater caves' - reports on the discovery by researchers and cave divers in Mexico's Yucatan peninsula of ocher mines that may be some of the oldest on the continent. Ancient skeletons were found in the now-submerged sinkhole caves.

Since skeletal remains such as those of "Naia", a young woman who died 13,000 years ago, were found over the last 15 years, archaeologists have wondered how they came to be in the then-dry caves. About 8,000 years ago, rising sea levels flooded the caves, known as cenotes, around the Caribbean coast resort of Tulum. Had these people fallen in, or had they gone into the caves intentionally? Nine sets of human skeletal remains have been found in the underwater caves, whose passages can be barely big enough to squeeze through.

Recent discoveries of about 900 meters of ocher mines suggest they may have had a more powerful attraction. The discovery of the remains of human-set fires, stacked mining debris, simple stone tools, navigational aids and digging sites suggest humans went into the caves around 10,000 to 12,000 years ago, seeking iron-rich red ocher, which early peoples in the Americas prized for decoration and rituals. Such pigments were used in cave paintings, rock art, burials and other structures among early peoples around the globe. The early miners apparently brought torches or firewood to light their work, and broke off pieces of stalagmites to pound out the ocher. They left smoke marks on the roof of the caves that are still visible today.

"While Naia added to the understanding of the ancestry, growth and development of these early Americans, little was known about why she and her contemporaries took the risk to enter the maze of caves. There had been speculation about what would have driven them into places so complex and hazardous to navigate, such as temporary shelter, fresh water, or burial of human remains, but none of the previous speculation was well-supported by archeological evidence," explain researchers from the Research Center for the Aquifer System of Quintana Roo, known as CINDAQ for its initials in Spanish. The research was published Friday in the journal Science Advances.

CINDAQ founder Sam Meacham states that "Now, for the first time we know why the people of this time would undertake the enormous risk and effort to explore these treacherous caves - to prospect and mine red ocher". Roberto Junco Sánchez, the head of underwater archaeology for Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History, reported that the discovery means the caves were altered by humans at an early date. The early miners may have removed tons of ocher, which, when ground to a paste, can be used to color hair, skin, rocks or hides in varying shades of red. "Now we know that ancient humans did not risk entering this maze of caves just to get water or flee from predators, but that they also entered them to mine." James Chatters, forensic anthropologist, archaeologist, and paleontologist with Applied Paleoscience, a consulting firm in Bothell, Washington, however, points out that none of the pre-Maya human remains in the caves were found directly in the mining areas.

Dr. Spencer Pelton, a professor at the University of Wyoming and the state archaeologist, has excavated a slightly older ocher mine at the Powars II site near Hartville, Wyoming. Pelton agreed that among the first inhabitants of the Americas, ocher had an especially powerful attraction. Red ocher mining "seems especially important during the first period of human colonization - you find it on tools, floors, hunt sites."

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 24 November 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 27 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 08 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 July 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 June 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 11 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 02 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 16 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 06 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 16 March 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 04 December 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 30 June 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 April 2023

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 24 November 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 27 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 08 September 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 19 July 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 06 June 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Friday 11 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Wednesday 02 March 2022

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 26 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Monday 16 August 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 06 July 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Thursday 06 May 2021

by Bradshaw Foundation

Tuesday 16 March 2021

Friend of the Foundation